The Tiniest Parasitic Fly in the World Is Named After Arnold Schwarzenegger

It’s just 0.395 millimeters long.

Brian Brown, an entomologist at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, is a connoisseur of the wondrously miniature. Of all of the insects that he intercepted in a tent-like trap set up in the Central Amazon, near Manaus, Brazil, last year, he was most smitten with the smallest. Measuring just 0.395 millimeters long, the specimen was barely visible to the naked eye, Brown says—and it turns out to be the most minuscule fly recorded to date.

“A fly that small is really difficult to find,” he adds. “It’s the smallest needle in the most incredibly huge haystack you can imagine.”

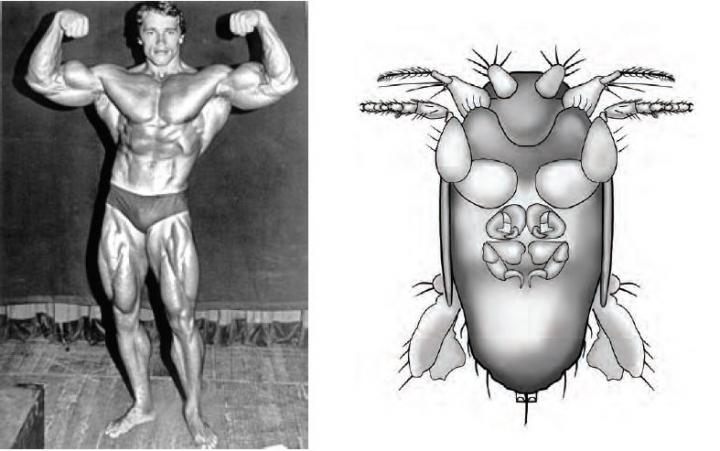

The specimen is female, and, as Brown describes in a new paper in the Biodiversity Data Journal, her proportions are startling. The head is large, the wings are stubby, and one set of legs is so disproportionately strong that Brown christened the fly Megapropodiphora arnoldi, in honor of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s once-chiseled physique.

“As soon as I saw those bulging legs, I knew I had to name this one after Arnold,” Brown said in a statement. “Not only is he a major cultural icon and an important person in the political realm, his autobiography gave me some hope that I could improve my body as a skinny teenager.”

Brown reckons that M. arnoldi is probably a parasite that prowls in termite or ant nests, where those powerful legs give it a strong grip on its hosts. “The torn wing membrane is reminiscent of other phorid flies that shed their wings when entering a social insect colony” where they no longer need the bulky appendages, Brown writes.

Another M. arnoldi specimen—possibly a male—was also collected in the same haul, but that one was accidentally destroyed during the process of illustrating the finds. Brown recalls it being skinny with large wings, and surmises that those appendages could propel both male and female through the air while they mated.

Tiny insects fascinate Brown because of their dazzling miniaturization: They often have the usual suspects—eyes, legs, wings, genitals, a nervous system—but on a scale that feels impossible to comprehend. The smallest recorded insect, a wasp called Megaphragma caribea, manages to fit many of these structures on a body just 0.17 mm long— even smaller than some single-celled organisms.

Brown says that the quest for the smallest insects opens up new frontiers for biologists. The territory is relatively uncharted, and it’s promising. He estimates that scientists have only documented about 10 percent of the species of flies zipping around. “You can almost not run out of new things to discover,” he says. “It’s like looking at another planet.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook