Essential Guide: Bioluminescence

Foxfire in action (via Wikimedia)

Bioluminescence — the ability for organisms to generate their own light — has evolved independently at least 50 times. All around the world, oceans glow, trees sparkle, and the forest floor flashes. It may be difficult to see many of these phenomena, but take a tour with us and be transported to one of nature’s most awe-inspiring spectacles.

GLOWING CAVES

Waitomo Glowworm Caves (photograph by Opticoverload/Flickr user)

The blind animals that live in the darkness of caves are well known. But not all cave dwellers are blind, and for their visual benefit, some creatures create dazzling light shows.

Waitomo Glowworm Caves (photograph by wanghui/Flickr)

Waikato, New Zealand — Waitomo Glowworm Caves

Since they were discovered in 1887, the Caves of Waitomo have inspired wonder with their long, glowing blue icicles. Well, they’re not actually icicles—they’re long strands of mucus with fungus gnat larvae on them. The larvae use the lights to attract insects into the sticky strings, where they are consumed. Regardless, they’re a delightful sight and tours are available.

Glowworm in Dismals Canyon (via dismalscanyon.com)

Phil Campbell, Alabama, United States — Dismals Canyon

The “dismalites,” as they are known locally, are a different fungus gnat larvae from the New Zealand glowworms. Rather than build hanging strings, they construct a web-like lattice of mucilage on the ceilings and walls. The result? If you turn off your flashlight, the rock glows as though it’s filled with tiny blue stars. Like their cousins in New Zealand, the dismalites are hoping to attract a meal, but they don’t mind if you watch.

Glowworm tunnel (photograph by Christian Reusch)

Wollemi National Park, Australia — Newnes Glow Worm Tunnel

Not all glowing places are made by nature. When the Newnes railroad tunnel was shut down in 1932, our friends the fungus gnat larvae moved in. The 600 meter (2000 feet) long tunnel provides the darkness, and the larvae provide the light show.

SHINING SEAS

The red tide on the Jersey Shore (photograph by catalano82/Flickr user)

The ocean itself appears to glow in many parts of the world. Many microscopic organisms — including the dinoflagellates that cause the toxic “red tide” effect — color the surf at night as well as during the day. On these beaches, your footprints may glow with tiny dots of light. While the effects are often seasonal, as in the Maldives or with the amazing display in San Diego, in some places the glowing persists year round.

Mosquito Bay (via Atlas Obscura)

Vieques, Puerto Rico, United States — Mosquito Bay

Despite its unappealing name, Mosquito Bay is the capital of bioluminescence. Due to a quirk of geology, this small inlet concentrates light-producing organisms allowing you to swim in a liquid envelope of light. You can even see fish swim by as they leave glowing trails behind them. One warning though: despite the name, don’t wear insect repellent for your encounter. It kills the very creatures you’re there to observe.

Glistening Waters (photograph by Josh Kesner)

Falmouth, Jamaica — Glistening Waters

The term “glow of youth” takes on a new meaning where the Martha Brae river meets the sea. Local folklore claims that the waters here restore youth in women, and have an “aggrandizing” effect on men. And maybe it works: Falmouth, Jamaica, is the birthplace of Usain Bolt and Ben Johnson, two of the fastest people on Earth. Regardless, the waters here glow year-round and you’re invited to bask in their radiance.

Gippsland Lakes (photograph by Phil Hart)

Gippsland, Victoria, Australia — Gippsland Lakes

Not to be outdone by the Caribbean, Australia’s Gippsland Lakes are home to Noctiluca scintillans, and with a name like that you know they glow. During 2008 and 2009, conditions were perfect for these microscopic creatures. By day, the waters were an odd red color and at night they burst with blue light. Even rain drops caused glowing blue ripples across the surface. While the effect has lessened over the years, on a moonlit night you can still catch a blue glow as you splash about.

FIREFLIES

Fireflies at night (photograph by Steve Hoefer)

Whether you call them fireflies, lightning bugs, or polyphaga, these night lights are the best known bioluminescent organisms. Their lights are typically used to attract mates, though some use their lights to trick other species into becoming a meal. The young glow, too, and when found are referred to as “glow worms.” Many rural spots in the United States feature nightly displays, but the spots below truly shine.

Fireflies in the Great Smoky Mountains (via Atlas Obscura)

Elkmont, Tennessee, United States — Great Smoky Mountains Lights

The fireflies of the Great Smoky Mountains perform a special show, but for only two weeks in June. Not content to just blink randomly, they gather at about 10 pm and flash together, like a string of Christmas lights with a blinker. This phenomenon was only recently discovered, and it’s possible that more populations like this will be found.

Fireflies in Kampung Kuantan (via Atlas Obscura)

Kampung Kuantan, Malaysia — Flashing Fireflies of Kampung Mountain

The fireflies of Kuantan also learned a special trick. In order to truly impress, the kelip-keilip — as they’re known locally — flash independently and then synchronize, creating waves of light in the trees. If the fireflies of the Smoky Mountains are Christmas lights, these little guys are a rave. There are fewer now than there used to be, but they’re still worth a look.

OTHER LAND LIGHTS

Fireflies aren’t the only land crawlies to put on a light show. Several other animals have developed ways of producing light, and for different reasons.

Termite mount in Golas (via DivineImpressions/YouTube)

Goias, Brazil — Termite Lighthouses

If you’re wandering Brazil’s rugged Emas National Park at night, you might be perplexed to see a small hill with dozens of glowing lights in it. And while you might recognize the hill as a termite mound, you might not know that the very bright lights are produced by the young of the hungry Headlight Beetle. The larvae hatch in the mound and glow to attract flying termites and other insects, of whom they make a meal. If you’ve ever had termites in your home, you may find some justice in the knowledge that they have pests in their homes, too.

Glowing Millipede (photograph by edenpictures/Flickr user)

Porterville, California, United States — Glowing Millipedes of Death

If you’re a millipede that secretes the potent poison cyanide, why not advertise it? The millipede Motyxia does just that by glowing an eerie blue which warns mice and other hungry night predators. Experiments have shown that animals that make the mistake of nibbling on Motyxia learn their lesson and don’t come back for seconds.

An agitated earthworm (photograph by Milton J. Cormier)

Hawkinsville, Georgia, United States — Eerie Earthworms

Let’s say you’re a worm. A very large worm, nearly two feet long. You live underground to avoid any peckish birds and life is good. But then you realize that there are moles down there with you, and they think you’re delicious. What to do? Well, if you’re Diplocardia longa, you develop the ability to ooze glowing blue slime which sticks to your predator and confuses them in this normally lightless environment. Some of their Australian relatives have learned this trick as well, and not too far from the glowing lakes mentioned above.

A Quantula snail (photograph by budak/Flickr user)

Singapore - Blinking Snails

Singapore is a modern city, and you might think all the interesting glowing animals would have been driven out long ago. But this species of unassuming snail thrives in environments where there are people, such as front yards and trash piles. After hatching from a glowing egg, Quantula start to blink and continue to do so as long as they’re moving. Fast moving means fast blinking. Eating only rates a half-blink. Why do they blink? No one is really sure, but it could be just to keep in fashion with Singapore’s Vegas-like nightlife.

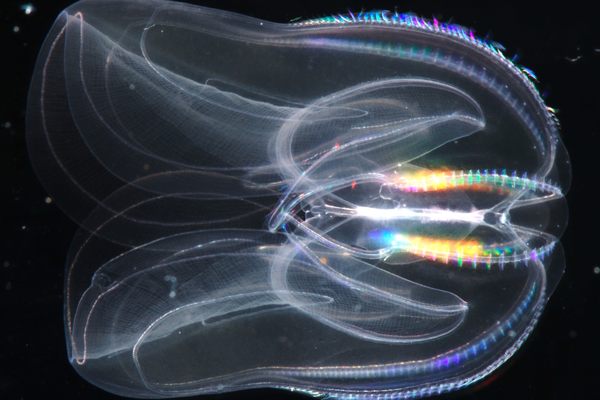

LIGHTS OF THE DEEP

Glowing coral (photograph by lapin1/Flickr user)

It’s estimated that 90% of deep-sea creatures produce light. Some do it to startle, some to attract prey. Others do it to blend in with the lighter waters above. Unfortunately, the ocean deeps are very hard to visit. In fact, many of the species we know of have never been observed alive. Fear not though, there are many glowing oceanauts we can see, and some of the most spectacular are listed below.

Glowing clams (via Knight Scientific)

West Dorset, England — The Glowing Clams of Great Britain

Oh, there’s nothing quite as quiet as a clam. The common piddock doesn’t need to make noise to get our attention. Not only does it bore into rock, it also glows like fire, especially when eaten. Romans are said to have covered themselves with the glow during orgies, and 19th century studies of this bivalve helped us understand the chemical properties of bioluminescence. You can find them in many places in Europe.

Firefly Squid (via Atlas Obscura)

Toyama Bay, Japan — Firefly Squid

Firefly Squid, as you might imagine with a name like that, give off light. Normally living at a depth of 350 meters (1200 feet), they employ glowing tentacles to scare off any predators. In Japan though, they’re brought closer to the surface by currents and are caught in fishermen’s nets in great numbers. When the nets open, the deck is engulfed with glowing blue light that sloshes and even jumps. Sightseeing boats will join the fishing just to see the spectacle.

Caribbean coral (via Wikimedia)

Bloody Bay, Little Cayman — Coral Wall of Light

Bloody Bay was named for its pirate heritage, but just beneath the waves lies the real treasure: a coral wall that drops 300 meters (1,000 feet) to the bottom. A very popular attraction, night divers have noticed that the coral glows at night. Though the drop is large, it’s not far from shore and even a beginning diver can enjoy the phenomenon. Bring a black light for bonus fluorescence.

FOXFIRE

Foxfire mushrooms (photograph by Angus Veitch)

There are many species of fungus that glow around the world. Known as foxfire or fairy fire, the phenomenon was much better known before the invention of electric light. A walk through many forests on pitch black nights will reveal glowing mushrooms of many sizes on rotten logs, stumps, and in clear space. But there is one honey mushroom that deserves special mention.

Glowing mushrooms (phtoograph by Angus Veitch)

Malheur National Forest, Oregon, United States — World’s Largest Glowing Organism

At 2,400 acres in size, this particular Honey Mushroom is the largest organism on Earth — glowing or not. But it does glow, and we can be thankful for that. While many people think of an individual cap as one mushroom, the reality is that it’s just one part of a much larger creature, and most of the fungus is underground. In the case of the Honey Mushroom, it’s also eating the nearby trees from the bottom up.

SPECIAL MENTION — SONOLUMINESCENCE

Up until now, every form of bioluminescence mentioned has been chemical. Normally, the enzyme luciferase interacts with luciferin to produce a blue or green light. But if bio (life) luminescence (light) means any light created by an organism, we have to include the following amazing creature.

A pistol shrimp (via OpenCage/Wikimedia)

Sanibel, Florida, United States — The Pistol Shrimp

Ding Darling Wildlife Drive on Sanibel is an amazing place to experience nature, but most people don’t realize that just below the surface of the brackish waters, pistol shrimp are performing amazing feats of physics. These small shrimp hunt with their enlarged claws, but they never touch their prey. Instead, they cock a claw back like a revolver, and fire a bubble. And while you’d think a bubble wouldn’t be the most harmful thing in the world, this bubble collapses so violently that it rips the water apart, producing temperatures hotter than the surface of the sun, and giving off a flash of light. You can hear them too—they sound like Rice Krispies.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook