Can You Really Hear a Coin Drop From the Back Row of an Ancient Greek Theater?

An acoustic study sparks a classical kerfuffle.

Tourists come from far and wide to visit the 2,300-year-old Greek theater of Epidaurus, where they stand in one of the back rows, scrunch up their eyes, and listen for the far-off sound of a coin being dropped or a piece of paper being ripped by a tour guide standing on the stage. Like other amphitheaters of the period, it’s supposed to have legendary acoustics. But the sonic properties of this theater may not be as dazzling as they’re made out to be, say scientists at Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands, who presented their findings at the scientific conference Acoustics ‘17 Boston earlier this year.

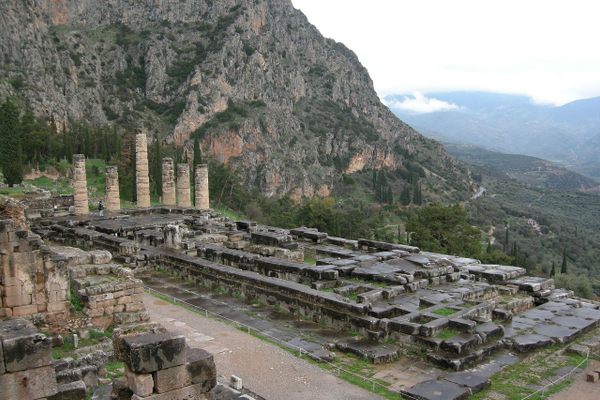

The team took multiple sound measurements from hundreds of spots across the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, the theater of Argos, and the theater of Epidaurus to get a wider picture of the audibility of sounds throughout the auditoriums, at various times of the day to reflect changes in humidity and temperature. They focused on the sounds often demonstrated to tourists—falling coins, tearing paper, a whisper. These, they found, were not audible from the back rows, as they are often said to be.

The study has sparked a commotion among classicists, however. In a statement given to the Times of London, the Hellenic Institute of Acoustics said that the findings “lacked sufficient scientific evidence,” that the conclusions were “arbitrary,” and that it would be requesting a “thorough review of their findings.” Many scholars and journalists have posited that the study purports to measure the acoustics as they would have once been, thousands of years ago. According to Remy Wenmaekers, coauthor of the study, this reaction came because of confusion over what he and his team had set out to study. “What we investigated was the current theaters, as they are right now,” he says. “Our conclusions are saying nothing about what the theaters would have been like 2,000 years ago, and our expectation is that they were very different.”

There is no shortage of reasons why today’s acoustics may be different than those heralded in ancient literature, Wenmaekers says. Ancient theaters may, for instance, have had decorative backdrops behind the stage that helped bounce sound to the cheap seats. “That would probably have quite a big impact on the acoustics,” he adds.

Further, Armand D’Angour, musician and classical scholar at the University of Oxford, mentions that the degradation of the theater’s surfaces has an impact as well. “The original theater surfaces would have been shiny, because they’d have been polished marble, whereas they’re now very rutted.” There’s still much that remains unknown about the other ways the ancient Greeks projected sound, he says, and whether that included the placement of additional objects around the theater to help project sound farther. “Clear voice was the most positive adjective you could use of a herald or of a singer,” he says. “In order to achieve that clarity, the people who built these theaters would have known all kinds of things.”

Finally, acoustics both modern and ancient can be profoundly influenced by the psychological state of the listener. D’Angour describes the intense focus one might have at the theater. “Maybe that changes you the way you actually listen out for sound,” he says. Theater tour guides might also use a kind of psychological groupthink as a trick of the trade. “Nobody dares to say that they didn’t hear it,” says Wenmaekers, “because if somebody hears it and you don’t—well, you feel stupid. That is how it works.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook