A Violent 15th-Century Freshman Hazing Ritual Involving Boar Tusks and Razors

The Deposition ritual, inflicted on Swedish and German students by faculty, was not for the faint of heart.

Fifteenth-century European universities had a problem. Their incoming students were young and unruly, so confident in their own abilities that they did not apply the requisite level of effort in class. So universities instituted hazing requirements; before their education could begin, new students needed to complete humiliating tasks in order to be purged of their pride, gluttony, and other sins.

According to The Medieval Magazine, some of these hazing rituals included becoming a de facto servant to an upperclassman—as at the University of Avignon in France—or paying for other students to go to the baths (which was deemed immoral only when the university faculty weren’t also invited).

But perhaps the strangest and most elaborate of the hazing rituals was Deposition, a practice that predominated with slight variations in both Germany and Sweden beginning in the late 1400s In order to enroll in their chosen universities, students in these countries endured a bizarre series of tests that makes the modern college application process look simple.

The best recorded accounts take place at Uppsala University in Sweden in the 15th and 16th centuries, but the practice existed in most of Germany at the time as well. Details vary slightly, but Deposition seems to have worked like this:

When new students—all of whom were male—arrived at a university, they announced their presence to the dean. Then they waited. Once enough people requested to study at the school, the dean scheduled a Deposition, so that the new students could formally enroll.

On the chosen day, students arrived at the dean’s office, where a Depositor—a faculty member appointed to conduct the ceremony—greeted them.

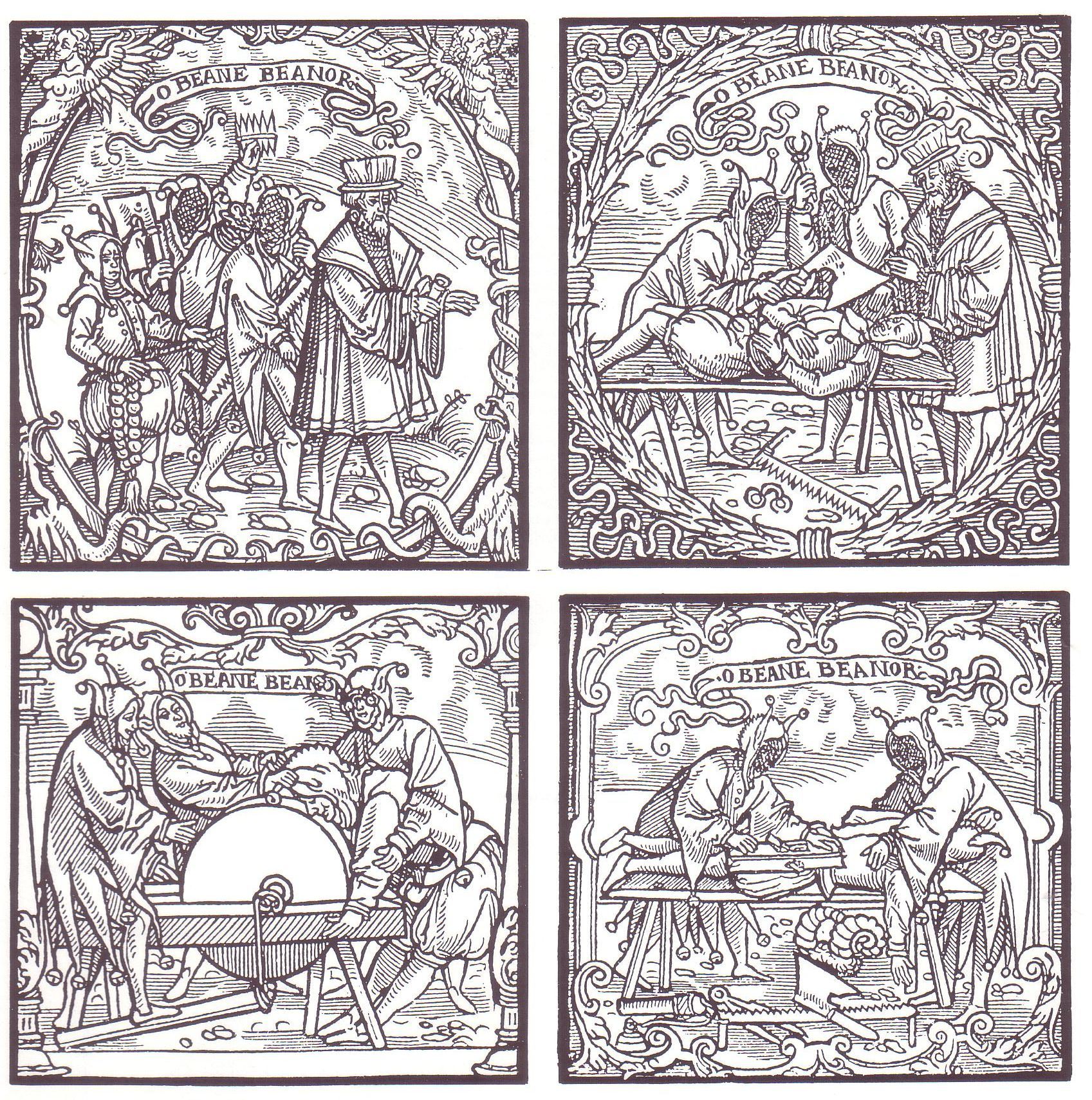

Once everyone was ready, the Depositor passed around odd items with which the students needed to adorn themselves: hats, looking-glasses, saws, razors, combs, shears, and clothes “of various patterns and colors.” Fake horns and fake donkey ears were attached to their heads.

The Depositor also asked students to open wide—and he inserted a boar tusk on each side of their mouths. They were expected to hold the tusks in place for the duration of the ceremony. The Depositor then marched them down the hall into a cavernous lecture room—though calling it “marching” is generous. The Depositor, in reality, spurned them forward with a stick as if they were “a herd of oxen or asses.”

Inside the lecture room, the students formed a circle around the Depositor, who proceeded to first insult them for looking like animals (they still had all varieties of horns attached to their bodies), then lecture them on “the vices and follies of youth” and the necessity “for them to be improved, disciplined, and polished by study.”

Then the Depositor began hitting them again. He whipped out a large sand-bag and started swinging wildly, sending the students “scamper[ing] about with all manner of laughable gestures and duckings.” A series of complex questions followed, sometimes in the form of riddles; if a student answered wrong or too slowly, the Depositor hit him some more. Often the students “received so many strokes with the sand-bag, that tears… started from their eyes.”

Yet because the students had—you know—boar tusks jammed into their mouths, even those who answered the questions correctly could barely speak. Their replies resembled a string of gargling sounds rather than actual words. The Depositor insulted them for this, too. He called them swine, and said that their tusks represented the sin of gluttony, “for young people’s understandings are obscured by excess in eating and drinking.”

Then he asked all of the students to renounce their sinful ways. If they did, the Depositor pried the boar tusks out of their mouths with a pair of tongs, symbolizing an end to their gluttony. He also removed their horns—which represented rudeness—and their fake donkey ears, which presumably represented their inner, donkey nature.

To follow the metaphor: the Depositor was stripping away the animalistic tendencies within the students.

But this was not the end of the Deposition—not even close.

Next, the Depositor instructed students to lie down flat on the ground. He went around to each student and filed their nails, “cleaned their eyes,” planed them, and “pretended to… saw off their feet.” In fact, at some point during this, “a beard [was] painted on” each student.

The Depositor also cleaned their ears “with an enormous ear-pick,” all the while saying:

“Let your ears be closed to protect you against fools;

I cleanse you for learning, not for vile buffoonery.”

According to some accounts, he then told prospective students to sit on stools, where he combed their hair and “shaved them so sharply with a wooden razor, that the tears”—once again—“started from their eyes.”

Once he was done, the Depositor chanted, “Literature and liberal arts will in like manner polish your mind,” and poured water over their heads—a symbol of their newfound purity.

“The buffoonery being ended by this washing, [the Depositor] admonishes the plane, scrubbed, and washed assemblage that they must commence a new life, strive against wicked impulses, and lay aside evil habits, which will envelope their minds just as their different garments envelope their bodies.”

Finally, the Depositor led the prospective students out of the lecture room and back to the dean, who gave a short speech, put salt in their mouths, said, “Let your conversation always be salted with salt,” and dumped wine onto their heads. Once was done, he “admonishe[d] the student thenceforward to lay aside all uncleanliness, and to live a pure life.”

After the ceremony was complete, the students received a Certificate of Deposition and, now sin-free, were accepted into the university.

In most German schools, the Deposition was not optional—a Certificate of Deposition was required for matriculation into the university. According to The American Journal of Education, the Deposition was “not merely a piece of buffoonery invented by the students, but was reckoned an officially authorized ceremony.” Statutes at the universities in Erfurt, Greifswald, and many more specifically praised the effectiveness of the Deposition ceremony.

In 1545, the University of Greifswald said:

“The Deposition is to be kept up. Such Beani [incoming students] as feel themselves free from school discipline, are inclined to idleness, and think themselves exceedingly learned, are to be somewhat sharply admonished during the Deposition how trifling their learning is, and how much they have yet to learn.”

By the early 1600s, Deposition had spread to the majority of German universities. Both Catholic and Protestant schools practiced it. Universities often justified the elaborate ceremony by referencing its supposed precursors: they pointed to other trials that students at the Academy of Plato or that Spartan warriors needed to endure in order to become mature.

Interestingly, as The Medieval Magazine notes, Deposition may have actually begun as a joke—its first textual appearances appear to be satirical—and then morphed into a legitimate phenomenon.

But not everyone appreciated Deposition. Critics likened it to “stupid buffoonery” and called the practice “barbarous.” Eventually, these complaints resonated with the majority of aristocratic Germans and Swedes—by accident.

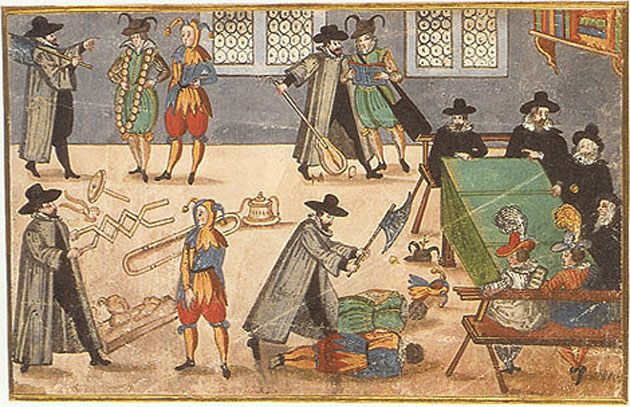

In Germany, the 1600s saw the birth of Pennalism, a hazing ritual that borrowed many of the themes of Deposition. But instead of lasting only one day, Pennalism continued for an entire year. New students who endured Pennalism soon suffered such great abuse that the public outcry forced universities to crack down on the practice. Though the backlash primarily targeted Pennalism, the two rituals had so much in common that universities decided to ban Deposition as well.

In 1717, Deposition was out at German universities in Tubingen, then at Wittenberg (1733) and Altorf (1753).

But without Deposition, the need to purify sinful students remained. German universities instituted alternate measures. The University of Halle, for instance, discontinued Deposition in 1694 but retained the requirement that new students “be examined by the dean of the philosophical faculty” and “be admonished of the piety, modesty, and manners which befit an ingenuous youth.”

Sins: cleansed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook