How Humans Have Embraced Life, With Images of Death

Masterpieces of memento mori.

In the early decades of the 20th century in America, death ceased to be part of everyday life. It was whisked away from its traditional place in the home, where people died surrounded by loved ones, where corpses were displayed. It had moved to the hospital and the funeral parlor.

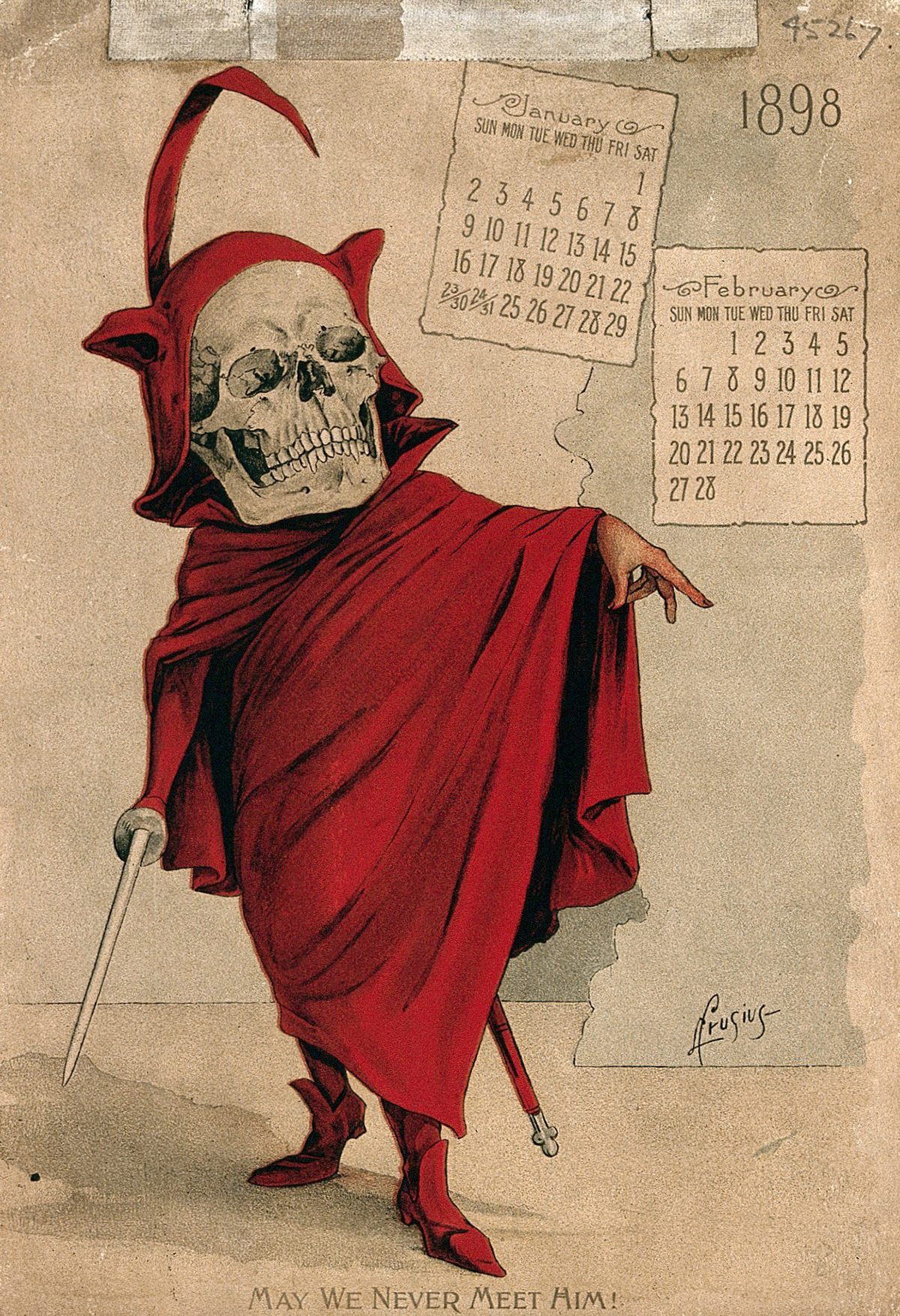

Previously, death was something to be considered and contemplated, and this took artistic form in the long history of the Christian tradition of memento mori. This concept—drawn from Latin, “remember that you have to die”—imbued all types of art, cemetery symbolism, and jewelry.

This fleeting nature of life was acknowledged in texts, from the Bible (“Therefore keep watch, because you do not know the day or the hour,” Matthew 25:13) to inscriptions on sundials (“It is later than you think,” or “The last hour to many, possibly you”). Far from being regarded as morbid, these reminders of mortality were prompts to embrace life.

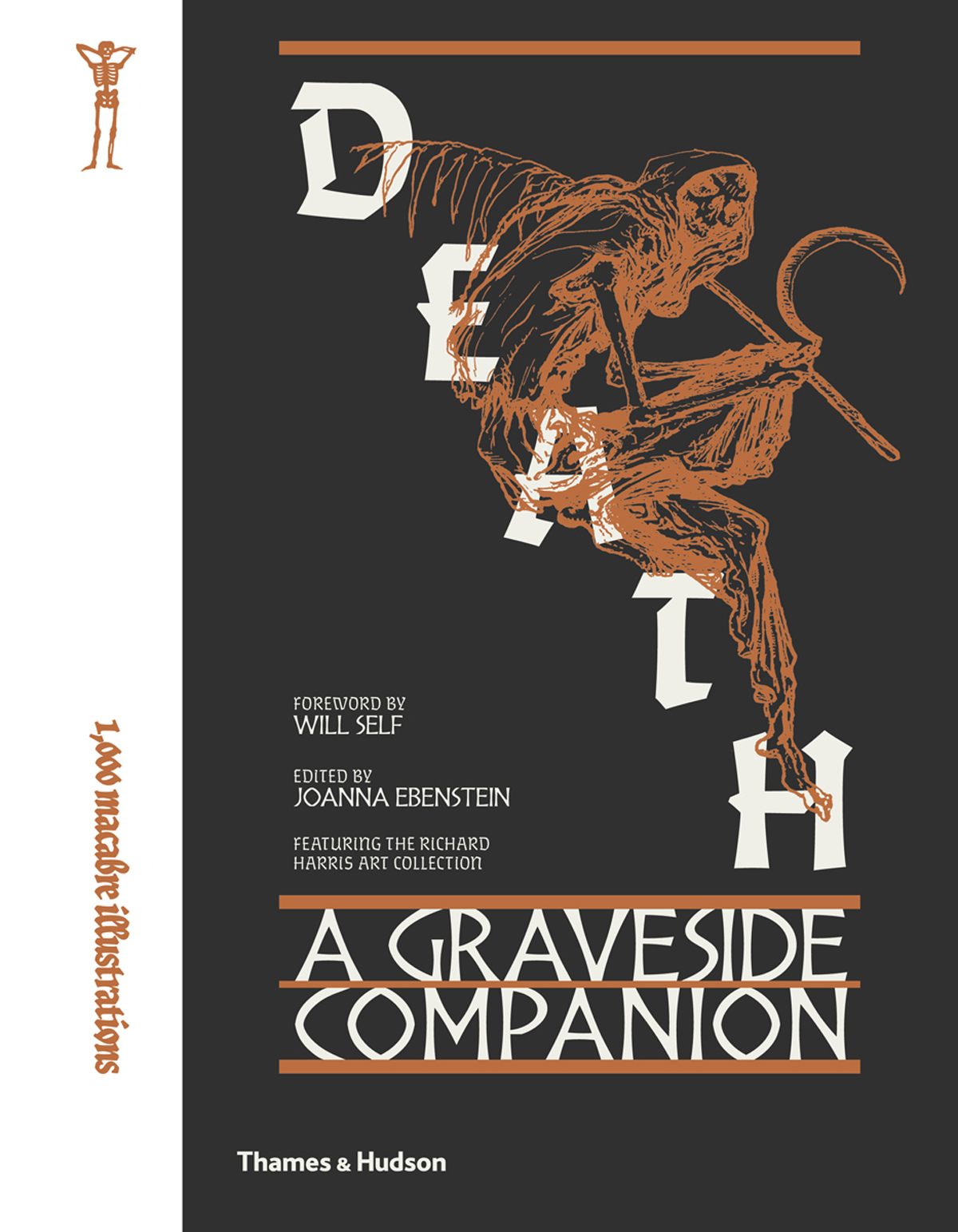

Yet today, argues Joanna Eberstein in the new book Death: A Graveside Companion, mortality is a fact to be ignored—or fixed. “The contemplation of death is no longer seen as a tool for living a better life,” she writes in the book’s introduction, “it is instead a problem to be solved.” Ebenstein is an expert on the subject. As the founder of the Morbid Anatomy blog and Museum (which closed in 2016), she is immersed in the realities and depictions of human mortality.

The images in the book include everything from The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, tiny dollhouse murder scenes created in the 1940s for forensics students, to the tradition of the danse macabre, popular artworks that show skeletons cheerily ushering people—irrespective of age, status, or wealth—to their graves. There are also more literal reminders, such as the portraits of half-skeleton, half-human figures, or optical illusion postcards in which scenes from life form the shape of a skull.

Atlas Obscura has a selection of images from the book for you to savor—while you still can.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook