The Mysterious Death of the Namesake of the Douglas Fir

Was David Douglas trampled by a wild bull, or lured into a trap?

Hidden off the beaten path on the slopes of Mauna Kea, the dormant Hawaiian volcano, there’s a rough stone spire that marks the spot where the famed botanist David Douglas is said to have died. But what this monument to the namesake of the Douglas-fir doesn’t allude to is the story of the strange events surrounding Douglas’s death. There is no mention, for example, of the former convict who will likely always be implicated.

“One lives through hell, while the other does what British people love most, which is finding things for gardens,” says Peter Mills, a professor of anthropology at the University of Hawaii at Hilo. “These two [men] meet up for breakfast on the other side of the world, and from that moment on, one is dead and the other’s life is forever changed.” Mills has studied the details of Douglas’s death, and to his mind, what happened is less of a mystery than it is a classic case of 19th-century classism.

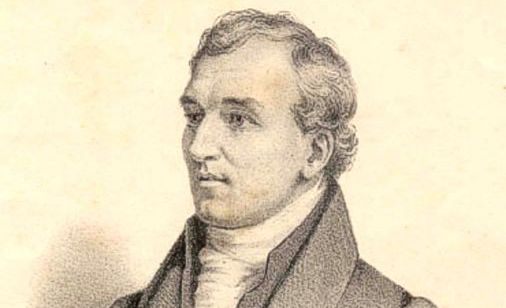

First, some background. Douglas was born in the Scottish village of Scone, and grew up gardening in a nearby palace before attending a series of prestigious schools to learn botany and horticulture. During the mid-1800s, he traveled to America a number of times to research, collect, and catalogue the flora of the country. On his second trip, in 1824, he set out to explore the Pacific Northwest on a plant-gathering mission for the Royal Horticultural Society. It was after this excursion that he became forever associated with Pseudotsuga menziesii, now called the Douglas-fir (even though technically it is not a fir, since it does not belong to the genus Abies, but who’s counting).

Douglas returned to England in 1827, bringing the Douglas-fir and a large number of other plant species along with him. All told, the botanist ended up importing some 240 different species of plant life to Britain, but his adventures didn’t end there. He would make one final voyage to the Americas in 1832. For two years, he explored the Columbia River and the area around San Francisco, before finally arriving on the Big Island of Hawaii in 1834.

Not long after he arrived, Douglas learned that he would have to stay in Hawaii for several months before he could secure passage back to Britain. In the meantime, he decided to hike the area on and around Mauna Kea, staying with some locals on his way. On the morning of July 12, he stopped by the hut of one Edward “Ned” Gurney to ask for directions, and ended up staying for breakfast.

Gurney was an Englishman from Middlesex, about the same age as Douglas, but the two couldn’t have been more different. “Gurney is raised just above street urchin,” says Mills. Where Douglas had come up surrounded by education and palace finery, Gurney had run afoul of the law at an early age and had been paying for it ever since. According to Mills, Gurney had been caught stealing around three shillings worth of lead fixtures off a house, and as punishment, he was sent to the infamous Botany Bay penal colony in Australia. At the time there were only three sentences for those sent to the Australian penal settlements: 7 years, 15 years, and life. Gurney got the lightest sentence.

Eventually Gurney was sent to work on a ship, and by simply disembarking in Hawaii, he was able to start a new life. He became a cattle hunter, establishing himself in a hut on the slopes of Mauna Kea. Gurney had been on the island for years by the time Douglas stopped by for breakfast that fateful morning.

It’s unclear what the two men talked about during their meeting. What we do know is that once Douglas left Gurney’s hut, Gurney followed him for a bit, warning him to look out for some pit traps he had dug to catch wild cattle. Later that day, Douglas was found dead in a cattle pit, having been trampled by a wild bull that had fallen into the pit on top of him.

Gurney was informed of Douglas’s death by a pair of locals, and rushed to the scene. “What Gurney does is, he shoots the bull, he gets the body out, he pays these guys to take the body about seven miles down the hill. [And this is] after sewing it up in a leather hide, so that the body can be brought to Hilo, the main town there where missionaries are hanging out,” says Mills. “Which isn’t, to my mind, the actions of a guy who just killed him.”

Gurney accompanied Douglas’s body to Hilo, bringing Douglas’s terrier, Billy, and the dead man’s remaining possessions with him. He gave his version of the events surrounding Douglas’s death to the local missionaries, and everything seemed to be in order. Yet almost immediately, suspicions began to swirl about Gurney’s role in Douglas’s death. Rumors spread that Douglas had been careless in flashing his money in front of Gurney. “One of the reasons he was suspected was that he was a Botany Bay convict. You say it and immediately you have this sense of a blood-thirsty kind of guy,” says Mills.

Rumors that Gurney killed Douglas continued to dog the cattle hunter for the rest of his known life. Mills says that a thorough investigation into Douglas’s death did take place, and the botanist’s wounds were deemed consistent with being trampled by a bull. But each time the story of Douglas’s death was revisited, mention of Gurney’s possible role just kept coming back up. Even today, Gurney is almost exclusively remembered as the man who may have killed David Douglas, even though he was never convicted of the crime.

Douglas was eventually buried in a common grave at Honolulu’s Kawaiaha’o Church. In 1856, a grave marker was installed at the church, but not on his exact burial spot, as that remains unknown. In 1934, on the centennial anniversary of Douglas’s death, the Hilo Burns Club, a Scottish heritage organization named after the famous poet Robert Burns, erected a stone obelisk and brass plaque on the spot where Douglas’s body was found, along with 200 Douglas firs. The site is now known as “Kaluakauka” or “The Doctor’s Pit.”

What exactly happened to Douglas that morning may never be fully known, but whether his death was the result of a simple hiking accident or something more sinister, the lives of both he and Gurney effectively ended that day. “It’s rather tragic I think, on both sides,” says Mills.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook