The Computer That Ran for School President

In 1975, the Pro-Apathy Party had an IBM 360 at the top of its ticket.

In the spring of 1975, at University of Nebraska-Lincoln, a computer ran for student-body president.

It was the leading edge of the era of personal computers. The IBM 360, first released in 1964, was the first big overhaul of IBM’s computer mainframe since 1952. It had what was, at the time, notable amounts of storage—1024 KB. It was the computer that had helped men reach the moon.

It could probably handle student government.

The IBM 360 ran at the top of the ticket of the Pro-Apathy Party, with Rick Horton as its first Vice President and Ray Walden as its second Vice President. The party had been formed by a group of students who wanted to “make the point that student government was pointless and elitist,” says Walden. (Few students voted, and the party that won always featured candidates from the Greek system, which voted together.) The Pro-Apathy Party planned to declare victory when—yet again—only 10 percent of the student body turned out at the polls.

“We also advocated for pencil sharpeners in every classroom and some other things that seemed funny at the time,” says Walden.

The leadership of the Pro-Apathy Party came from an experimental university program called Centennial, which didn’t have regular classes. Instead, Centennial installed faculty as fellows who proposed and approved projects that students in the program could take on. It was mecca for coeds who wanted to live differently and challenge authority. (It has since been shut down.) Centennial students had previously formed a Surrealistic Light People’s Party, which promised to build an actual 60-by-90-yard platform as part of its platform, and even tried to levitate the campus bell tower. (There were many less-than-totally-seriously student political parties in this era in Lincoln, including a “Cut the Crap” party.)

The Centennial students who formed the Pro-Apathy Party carefully read the school’s election rules and discovered that while students had to submit their names for office, different names could appear on the ballot. So while Horton, Walden, and the party’s slate of senators all ran under their own names, Brian Thompson, the apathetic presidential candidate, did not put his own name on the ballot. He had the IBM 360 run in his place.

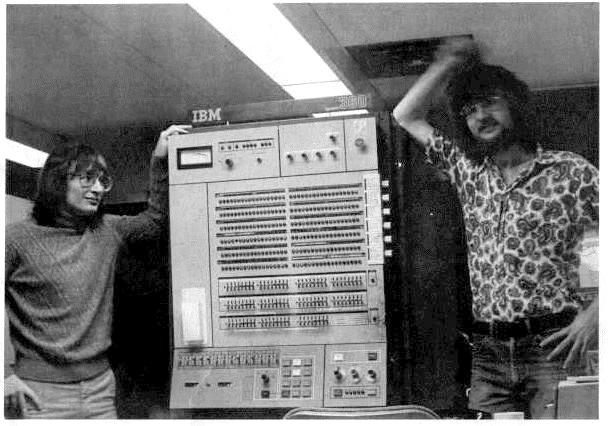

The ploy for attention worked. Pro-Apathy campaign posters featured a shot of Horton, Walden, and the IBM 360. (There were also posters featuring senatorial candidates snoozing in their chairs, and one with the party holding up spoons, a riff on a popular cereal ad campaign.) The party took the race seriously enough to argue for a slot in the debates, where Horton proposed strategies to reform the student government. The campaign also made the Daily Nebraskan, the student newspaper: “Pro-Apathy presidential candidate is a computer,” read the headline.

The competition for student body president that year was fierce. According to the Nebraskan, there were “enough independents to form a football team.” When it came time to vote, however, the Pro-Apathy Party was proven right. Only a fraction of students bothered—around 10 percent, as usual.

The IBM 360 did not win the election, but it did come in third in the large field, with 278 votes. “So we didn’t get to the point of having to deal with having some actually apathetic guy winning the presidency under the name of the mainframe,” says Walden. At least they made their point, and they had great pictures to prove it.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook