The Massively Friendly World of Competitive Giant Pumpkin Growing

Big gourds, small egos.

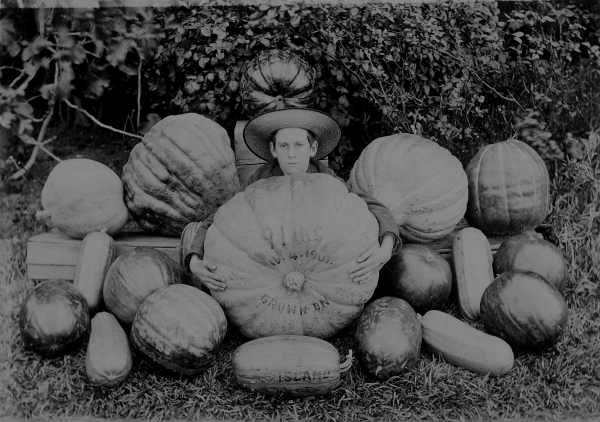

Some stand tall and sturdy in their orange armor. Others seem lumpier, like balloons deflating one week after a birthday party. All of them, however, are immense. These giant pumpkins, which are on display at the New York Botanical Garden, belong to growers who compete to create the season’s largest gourds. Some of them weigh over 2,000 pounds; all of them required time, land, and obsessiveness to grow. But a curious fact contributes to these gourds’ gargantuan size: They are the product of very friendly competition. In the charming world of competitive giant pumpkin growing, veterans and newcomers alike help each other get better.

Joe Jutras brought his 2,118-pound green squash to New York after setting a world record for heaviest squash at the Southern New England Giant Pumpkin Growers Pumpkin Weigh-off. The win made Jutras—a retired, high-end cabinet maker—the first grower to win the prestigious trifecta, a sort of Triple Crown feat that includes the heaviest squash, longest long gourd, and heaviest pumpkin titles.

Joel Holland brought his 2,363-pound pumpkin from California, where he won an annual weigh-off at Half Moon Bay. Holland owns Land O’Giants, a company that sells fertilizers, instructional books, and seeds for growing giant pumpkins.

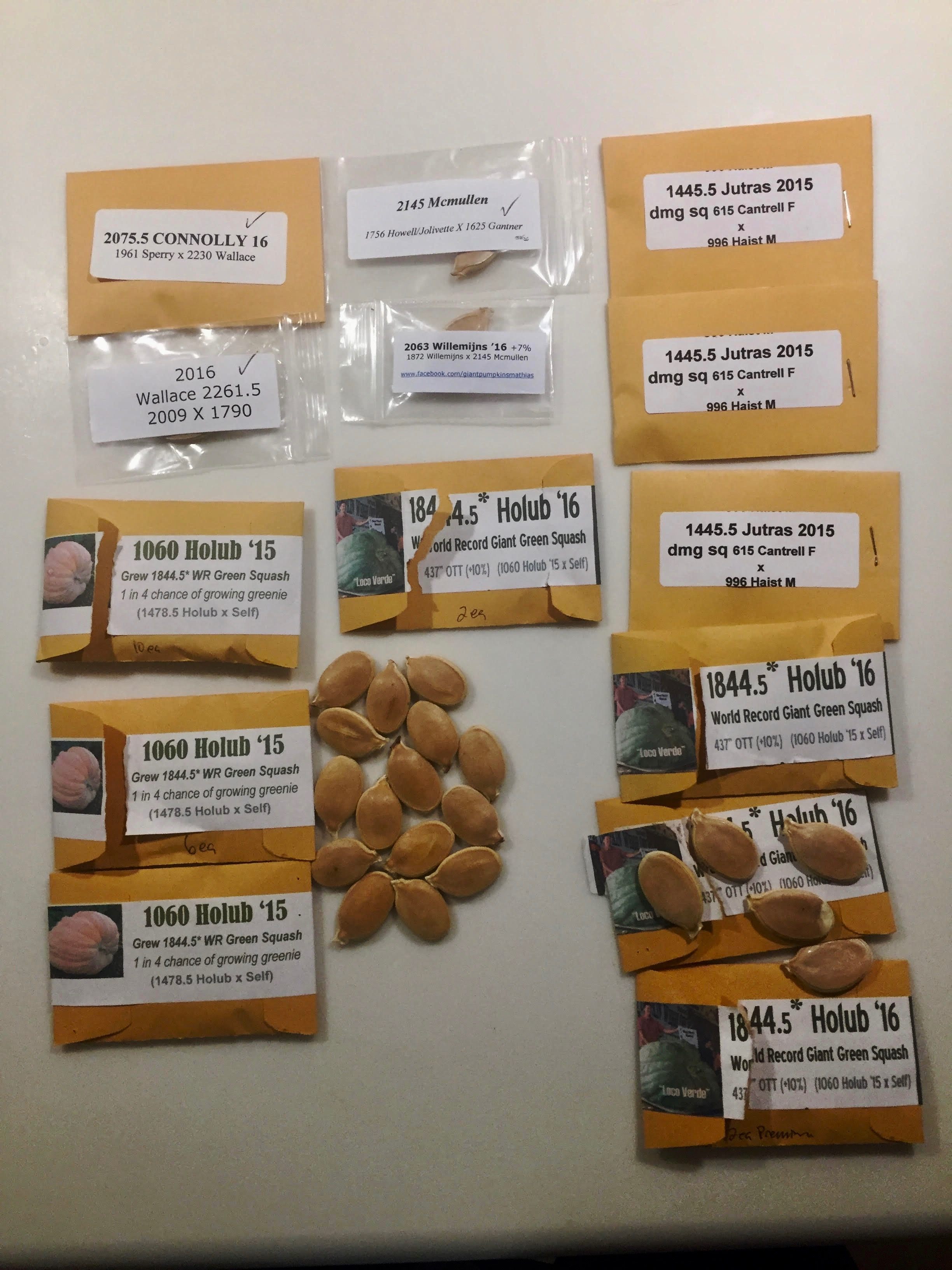

Holland’s willingness to share his hard-earned techniques is indicative of the growing world’s inclusivity. Giant pumpkin growing is rooted in spectacular competitions. Yet growers are far more likely to swap seeds than to, say, sabotage competitors’ crops.

“I think it’s a lot more open than it used to be,” Holland says. “When I first started, several growers were keeping their information secret, not always sharing seeds like they do now.”

On forums such as Bigpumpkins.com, growers debate fertilizers, discuss the exact dates when they hand-pollinate blossoms, and share photo diaries of their preferred growing methods. Jutras says growers around New England buy fertilizer together and hold yearly seed-starting parties where they “shoot the baloney” over a meal. “You don’t normally grow something this big without asking a lot of questions and having a lot of help from people,” he says.

What leads someone to care year-round for a fruit of nearly comical proportions? Both Jutras and Holland’s interest in big pumpkin growing (a sport or hobby, depending who you ask) stemmed from a lifelong enjoyment of gardening. The two men say they grew their first big pumpkins on a lark, and were surprised and encouraged by how easily they grew epic pumpkins. Holland’s first attempt weighed 244 pounds and won the largest pumpkin prize at the Washington State Fair. Jutras planted Atlantic Giant pumpkin seeds and “watered them like anything else.” His best pumpkin swelled to 212 pounds, and he was hooked.

The field has grown considerably since Jutras and Holland’s first experiments. A pumpkin first clocked in at over 500 pounds in 1984. But thanks to better fertilizers, a more talkative and international community of pumpkin growers, and improved seed stocks, one can now feasibly grow a pumpkin weighing over 2,000 pounds and still not be a top-ranked grower.

“That’s why these squash have gotten so big lately; it’s got pumpkin in its genetics,” says Jutras, who won this year’s competition with a seed bearing both the qualities of a pumpkin and squash. “Us pumpkin growers know the genetics of our giant fruit better than our own families.”

This understanding of genetics leads Jutras and Holland to build a portfolio of plants. “You have to kind of hedge your bets by planting several different seeds and having several different plants,” says Holland. That way, growers can suss out the best seeds, preferably from prize-winners of the past. Holland planted six pumpkin plants this year. While he planted them indoors in April, he didn’t know until August which one would be a standout. “Every little seed is a little different, so it’s a little element of luck involved,” Holland says. “You can extract two seeds out of the same pumpkin and get far different results.”

Similarly, Jutras started with twenty plants in twelve different greenhouse spaces. The experimentation paid off: Jutras’ record-breaking green squash grew about 39 pounds a day at its peak. He credits a series of new soil techniques involving solarization (in which people mulch and cover soil with plastic), “resting” the soil for a year (meaning he grew nothing on it), and putting mustard, a natural fumigant, and chicken manure on the soil.

In the spirit of competitive gourd growing, Jutras plans to share all his secrets. He will speak to local growers at an annual seed-starting party, and in February, he’ll likely regale a crowd of several hundred at the Great Pumpkin Commonwealth’s international conference in Portland, Oregon—an organization likened to the NFL of giant fruit and vegetable growing.

“We’re to the point where we pass out seeds, hand out information, invite everybody to come to our meetings and tell them everything we know,” Jutras says. “If people want to do the work, I hope they do and grow a personal best … We have a saying: ‘You don’t grow these from the couch.’”

Though growers’ main motivation is competitions, a market does exists for giant pumpkins and squash. Experienced growers find clients ranging from Las Vegas’s Bellagio Resort and Casino to nursing homes. At 75 cents to a dollar per pound, the heaviest pumpkins sell for several thousand dollars. Less heavy pumpkins can go for around $500. But the average grower doesn’t seen much of a profit, as costs range from several hundred dollars to $800 per plant, according to Jutras.

“It’s more of a labor of love than of profit,” Holland says. “But the joy of growing a giant pumpkin probably outweighs any monetary gain.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook