Solved: The 300-Year-Old Mystery of Barbados’s Pigs

Spoiler alert: They were probably peccaries.

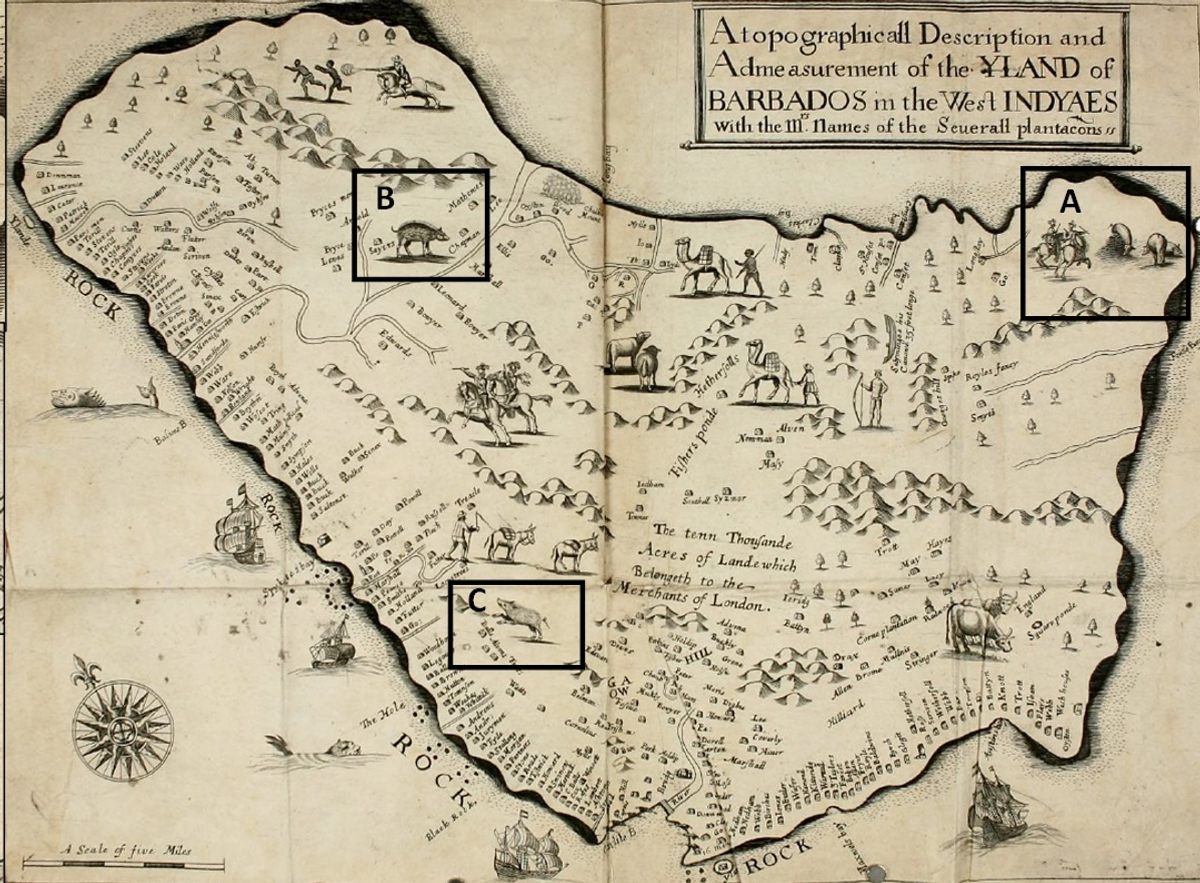

Richard Ligon’s 17th-century map of Barbados shows an island surrounded by sea monsters. Their tails are like mermaids; their faces like dogs. On the island’s interior, camels, part of a short-lived pack-animal importation scheme, raise their proud heads. Europeans on horseback shoot at an escaping slave. A lone Native American stands in the middle of the island. But the most mysterious inhabitants of Richard Ligon’s Barbados are also the most banal: five curly tailed pigs. Half of them are hairy and feral; the other half are smooth.

According to Ligon’s accompanying treatise, these pigs were dropped on Barbados by 16th-century Portuguese sailors, who counted on them as a food source for future expeditions. This was a common practice of early European sailors, who ensured themselves a decent meal by unleashing livestock in the most far flung of places, often harming ecosystems in the process. When the British arrived on Barbados in the 17th century, they described an island devoid of human inhabitants, but overrun with pigs.

For more than 300 years, most scholars accepted Ligon’s explanation of the pigs’ origins. (The Americas had no pigs prior to the arrival of Europeans.) But absent archaeological evidence, the story couldn’t be proven. Who really introduced the pigs to the island? Were they the same animals depicted in Ligon’s map? Could it be that, as one 19th-century scholar wondered, the animals weren’t pigs at all, but physiologically similar, though evolutionarily distinct, New World peccaries?

This debate over long-dead livestock may sound quaint. But in the contentious field of early American archaeology, these details flesh out an elusive history. The European colonization of the Americas was, perhaps, the most momentous event in human history, catalyzing unimaginable movements of people, animals, and cultures—and the deaths of 90% of America’s indigenous inhabitants, who were wiped out by war and disease. That’s an estimated 56 million people, or a tenth of the world’s population.

In the course of this cataclysmic transformation, European colonists drastically altered the American landscape, introducing horses, wheat, rats, sugar cane, and pigs. Once let loose, these pigs multiplied across North America and the Caribbean, disrupting local ecosystems and devastating entire indigenous communities with disease. By the time Ligon’s map was published in England in 1657, more than 150 years had passed from the moment of first contact, making it difficult for contemporary researchers to tell how colonization had altered these sometimes fanciful landscapes. The mystery of the Barbadian pigs, then, is part of a longstanding effort to understand the transformation of an entire world.

When Christina Giovas sifted through the Barbados Museum and Historical Society collection in 2014, she wasn’t thinking about pigs at all. An Assistant Professor of Archaeology at Simon Fraser University, Giovas studies Caribbean prehistory, tracing the species indigenous people introduced to the Caribbean long before Europeans arrived. While the British claimed to encounter no indigenous Barbadians—some scholars argue they had already fled or been captured in 16th-century Portuguese slave raids—Giovas says Barbados was first settled as far back as 2400 B.C. She was searching for traces of these early people’s ecological impact in the mammal bone collections of the Barbados Museum.

But Giovas found something surprising: a single, sharp-toothed fragment of a peccary jawbone. “That’s completely unexpected because we didn’t have any records of peccary introduction,” Giovas says. Giovas took the bone to her collaborators, George D. Kamenov and John Krigbaum, both of the University of Florida. By comparing the concentration of strontium isotopes in the peccary’s tooth to levels characteristic of Barbadian geology, Krigbaum found that, indeed, the peccary had lived on the island, most likely from 1645 to 1670. It looked like the mysterious Barbadian pigs weren’t all pigs—many were peccaries.

Giovas’s team suggests that, in accordance with the hairy and smooth specimens illustrated on Ligon’s map, there were actually two kinds of pig-like creatures on Barbados in the 17th century: smooth-skinned, domesticated pigs, and hairy, wild peccaries. While the peccaries could have been introduced by earlier Native Americans or by the British themselves, she says the time frame suggests that Portuguese or Spanish sailors let them loose, possibly while sailing by Barbados en route from their South American colonies.

There are no longer peccaries in Barbados. Like the brief, failed introduction of camels illustrated on Ligon’s map, their short-lived stint on the island is just one of the many strange, and often disastrous, ways in which Europeans shaped the ecosystems of the lands they colonized. For Krigbaum, these livestock histories don’t just tell us about people’s farming practices, but about their relationships to culture and the natural world. “Animals have as much to say about humans as do humans themselves,” he says.

While Giovas’s team found flaws in Ligon’s account, his map of the Barbadian pigs reveals much more than literal, factual history: It illustrates the desires that Europeans brought to the New World. It’s an imagined land brimming with violence and possibility, where sea monsters could mix with camels and psuedo-pigs—a land that Europeans, tragically, exploited as their own.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook