How Chinese Food Won Over the World

Chinese-Canadian filmmaker Cheuk Kwan tells a story of innovation and survival.

THIS ARTICLE IS ADAPTED FROM THE APRIL 1, 2023, EDITION OF GASTRO OBSCURA’S FAVORITE THINGS NEWSLETTER. YOU CAN SIGN UP HERE.

When I was in Guatemala, my friends took me to try what they called “Thai empanadas.” I saw a group of people tending to a griddle while speaking Mandarin, and immediately realized that these cooks were Taiwanese, not Thai. I ordered five-spice empanadas in Mandarin—a welcome relief from my poor Spanish—and immediately felt a little more at home.

As a Chinese-American, I’m always on the lookout for new versions of Chinese food. I’ve encountered Portuguese-Chinese food prepared in a clandestine third floor apartment-restaurant in Lisbon, chūka ryōri (Japanese-style Chinese food) in bustling Tokyo streets, and Chinese takeout in the mall of a South African resort town.

I’m not the only Chinese person who travels this way. Chinese-Canadian filmmaker Cheuk Kwan spent four years filming Chinese Restaurants, a 2006 documentary series spanning six continents and 14 countries. During the pandemic, he chronicled these experiences in a book, Have You Eaten Yet? Stories from Chinese Restaurants Around the World, named for a common greeting in the Chinese-speaking world.

Kwan, who now lives in Toronto, grew up between Hong Kong, Singapore, and Japan and speaks five languages. Everywhere he goes, he finds a taste of home in Chinese restaurants, peeking into the kitchen to connect with cooks and owners.

“Running a Chinese restaurant is the easiest path for new Chinese immigrants to integrate into a host society,” Kwan writes in Have You Eaten Yet?. “It’s a unique trade where no other nationalities can compete, and it provides work for new arrivals, whether legal or illegal, helping them get on their feet.”

Kwan’s project was inspired by a restaurant in Istanbul whose Muslim Chinese founder, a political leader in the Nationalist Party, fled China on foot over the Himalayas after the Communist Revolution. At a meal with the restaurant’s owners, Kwan was treated to halal Chinese dishes such as braised mutton and pan-fried dumplings with beef swapped in for pork.

In 2000, Kwan interviewed Noisy Jim who immigrated to Canada in 1937 during the Chinese Exclusion Act. In the 1950s, Jim opened the beloved New Outlook Cafe in the prairie town of Outlook in Saskatchewan, Canada. He built such close relationships with his loyal customers, who would come to chat and eat hearty Canadian and Westernized Chinese food, that he would lend them keys to the place so they could cook outside of business hours.

Restaurateur and minister Kien Wong was drawn to Haifa, Israel by faith. A member of Vietnam’s large Chinese population, Wong fled his home country by boat in 1978 and volunteered to be interviewed for refuge by an Israeli official so he could “spread the gospel in the Holy Land,” as Kwan writes in his book. He opened a restaurant and became a chef-preacher, proselytizing to Chinese immigrants and cooking them dishes like Cantonese-style St. Peter’s fish, caught fresh from the Galilee.

In the multi-ethnic island nation of Mauritius, Kwan interviewed Collette Li Piang Nam, a Hakka Mauritian woman who devised a fusion menu for her restaurant nestled in a sugarcane field. Since the 1800s, the Hakka Chinese minority has deeply integrated into the island’s Creole culture. Nam makes Kwan her house special: wok-fried fish in tomato sauce.

I spoke with Kwan about Malagasy wonton soup, the challenges faced by immigrant cooks, the global appeal of Chinese cuisine, and what he wishes more people knew about Chinese restaurants. Here is our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity.

Q & A with Cheuk Kwan

What would you say is the Chinese food culture overseas that surprised you the most?

Nothing surprised me as much as what I saw in Madagascar.

They were serving wonton soup for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Any Malagasy restaurant will serve it. Malagasies who run the restaurants call it soupe chinoise. It’s a “you-don’t-have-to-be-a-German-to-serve-a-hamburger” kind of thing. Authentic Chinese food is actually served as a national dish.

Were there any dishes that you tried in Chinese restaurants that seemed completely new to you?

No, not really. Because of my background, I’m very used to having all kinds of Chinese food. [But] there are cases like this: where I had ostrich meat, stir-fried in black bean sauce in South Africa. But that’s still identifiably Chinese, even though the ingredient is totally off the books for me.

Do you crave Chinese food when you travel?

Yes, that’s how I got into Chinese Restaurants. I always want to have some white rice and green veggies. After a while, all this pizza and pita bread gets to you. It’s just that Chinese stomach in me [laughs].

What’s the most memorable meal that you had?

[A] meal that I really enjoyed was in Argentina. It was parrilla [barbecue], and it was in the cottage of this guy we met. It was a beautiful, sunny afternoon and we were all eating and drinking in the garden and on the patio. I was meeting with my Chinese restaurant owner and his friends. They’re all kind of an older generation. They came from China, and here they are so far away from home. To me, that’s very poignant, in terms of meeting as friends and partaking in a meal that happens to be not Chinese, but also very local.

Why do you think Chinese restaurants have had such a big impact on the world?

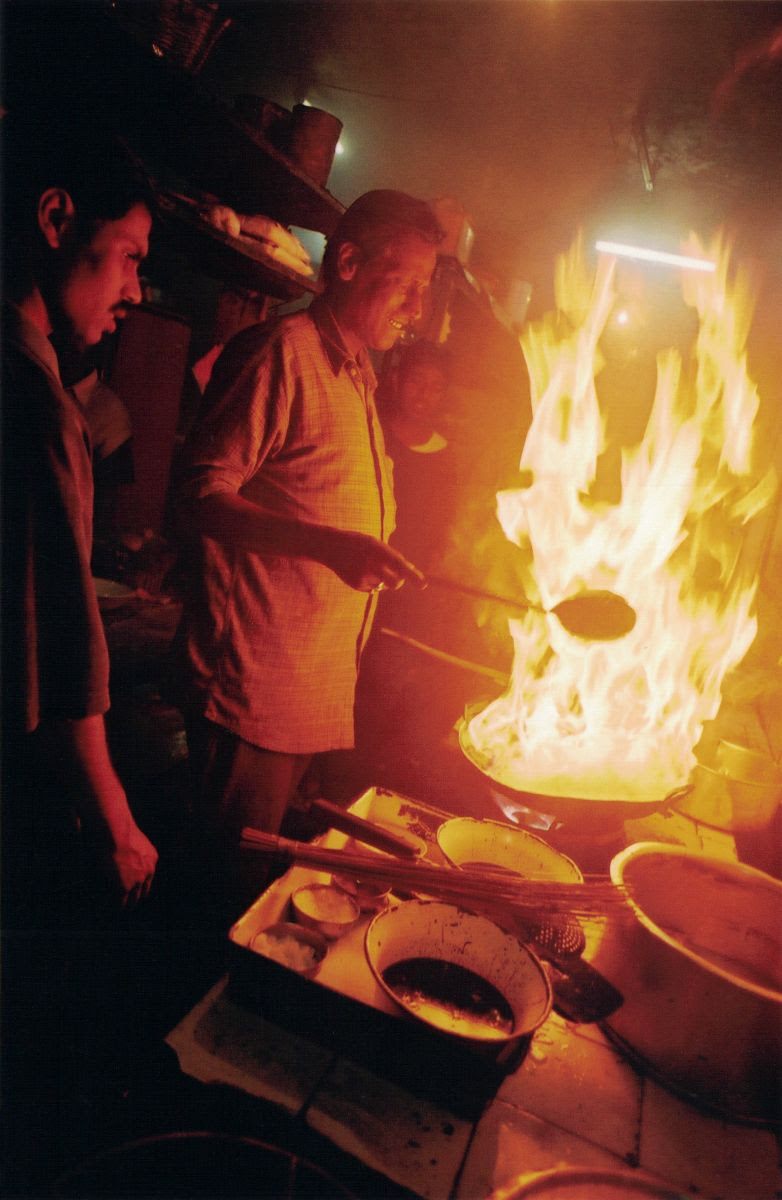

First of all, [Chinese food] is [often] distinctive enough from the native culture for people to really enjoy it and share it. But also, it’s appetizing enough for people to say, “I can have it every day.” You can do very elaborate Chinese food, but you can always do simple Chinese food as long as you have a wok.

A lot of it is the food, but also a lot of it is the people behind it. And that’s the crux of my storytelling: Who are these people who are behind this kitchen, behind the woks, and making up this fresh food that is adaptable to local tastes?

It’s that entrepreneurial spirit that you can even taste in your food.

Do you think that the people cooking Chinese food all around the world see themselves as trailblazers and entrepreneurs?

I don’t think so. I think the whole global phenomenon is a byproduct of just individual hard work, of people trying to survive. I think, if you look behind most Chinese restaurants—not the commercial ones, but the Mom-and-Pop family restaurants—it’s basically a story about immigration, diaspora, survival, and probably hardship and discrimination.

Is there a specific story of discrimination that’s coming to mind for you?

In Peru, Chinese people were really blatantly discriminated against and [were] indentured laborers. So you congregate in Chinatown and try to protect yourself in the enclave. They had to do a lot of incorporation of Peruvian food into Chinese food to survive, but then it took off, and people really liked it. So chifa [Chinese-Peruvian cuisine] then became the national cuisine of Peru.

Is there anything that you wish more people understood about Chinese restaurants?

A Chinese restaurant has that image of being a cheap eating place. People in Chinatown are saying, “Why can’t we be treated more like French food? You value that kind of thing, right?” Don’t treat Chinese restaurants like a cheap joint that you can go to for convenience.

In your book, you talked about the diversity of the Chinese diaspora itself. Why was that important to you?

I wanted to make my films for Chinese people and say, “You are not as pure as you think.”

All those maritime voyages and the Silk Road all brought cultures and people from everywhere, and they got mixed into the population. And of course, food-wise, too, Chinese food is not as pure as you think either. A lot of influences from other places.

That’s my message. When it comes down to it, we’re all one world.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook