The Ultimate Rich Kids Were the Children of Famous Explorers

Wealthy and entitled, as only the scions of conquistadors could be.

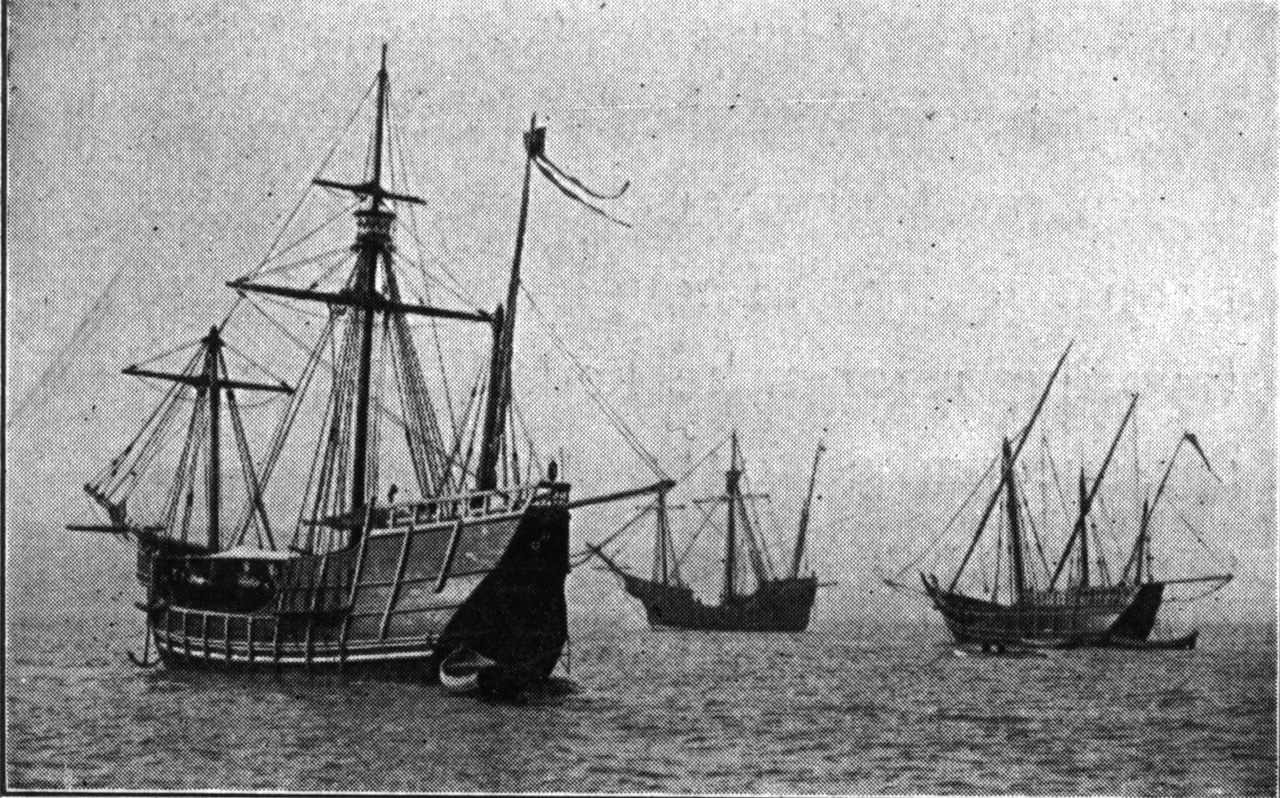

In 1523, Diego Colón, the eldest son of the man known as Cristóbal Colón—whom the United States calls Christopher Columbus—crossed the Atlantic Ocean for the last time, called back by the Spanish crown to answer for his actions in “New Spain.” Since his father had died, in 1506, Diego had been fighting to claim the wealth and power he believed he was owed, that Spain had promised his family.

He had managed to win the support of Charles V, the most recent king, but after Diego raised taxes in Hispaniola and invested in slavery and sugar plantations, the new king had started to see him as a rebel. For decades, the monarchy and the Colón family had been caught in a legal battle, a battle that would stretch on for centuries, over the wealth ripped from the “New World”—the labor of the people in colonized lands, the natural resources, and a share of the tax revenue sent back to Spain. Diego wanted more of it than, in practice, the monarchy was willing to hand over.

In history books, when the story of European exploration and colonialism is told, conquistadors and their sort take center stage. But after they died, whatever titles they’d been given or land they controlled passed to their children. While the names of these explorers are familiar—Ponce de León, Hernán Cortés, John Cabot, Francisco Pizarro—the fates of their children are less remembered, like many people who inherit wealth rather than make it.

Some took up their fathers’ profession, commanding ships of their own across the ocean, while others concentrated on keeping, or just spending, the wealth they’d been handed. Often, like Diego, they fought for more—whatever they thought their parents had been promised. Just as some wealthy families today turn their riches toward a legacy beyond the business, usually in culture or philanthropy, some explorers’ kids tried to solidify their family’s place in the elite and elevate their status. Thus the plundered wealth of the Americas became libraries, gardens, titles, and monuments (to the glory of the heirs).

The Colón Brothers

Of the two Colón brothers (half-brothers, actually), Fernando more closely fits the image of a rich kid today. Born into an exalted position thanks to his father’s accomplishments, Fernando lived a charmed life. Early on, he was inducted into the halls of power, serving alongside his brother as a page to the royal family. When he was 14, his father brought him along on business—a fourth voyage across the Atlantic to Hispaniola and back.

But for Fernando, colonialism didn’t stick. After his father’s death, he took a quick trip with Diego to Santo Domingo, and then returned to Spain just two months later, to oversee the legal battles between his family and the state.

In Europe, he pursued intellectual projects. He became a respected cartographer and an avid collector of books, using his family’s money to build one of the largest and most impressive libraries of its time. Fernando had a taste for modern innovation: Rather than focus on manuscripts, he bought printed books, some of the earliest made in Europe. He invested in his family’s legacy, writing one of the first biographies of his father and planting a garden filled with specimens brought back from the Americas.

While Fernando was spending money, Diego was trying to consolidate his family’s status as one of the most powerful families in the “New World,” with control over Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and Cuba. Before his father’s first voyage, in 1492, Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand had agreed that, if his quest succeeded, Cristóbal Colón would be entitled to 10 percent of the takings of his voyage, plus a bevy of titles. Every time Diego tried to claim what he thought he was owed, the crown fought back. When he died, his father’s legacy was still contested.

The monarchy’s legal case rested on the idea that it wasn’t Colón, but one of his ship’s captains, who had first discovered the Americas. Ultimately, Diego’s widow went into arbitration with the crown, and his son, Luis Colón de Toledo, came out with a title—Admiral of the Indies—control of Jamaica, an estate in Panama, and a 10,000-ducat annuity that was meant to last in perpetuity.

It was, perhaps, less than the Colón family thought they were owed and less than Cristóbal’s contract specified. But the Colón family came out ahead of other scions of conquistadors. These families represented a threat to the existing elite, and as more Spanish wealth-seekers and bureaucrats crossed the ocean, the ascendant heirs of explorers were often viewed with suspicion. The Cortés brothers, for instance, came close to being killed for their push to join the ruling class.

The Cortés Brothers

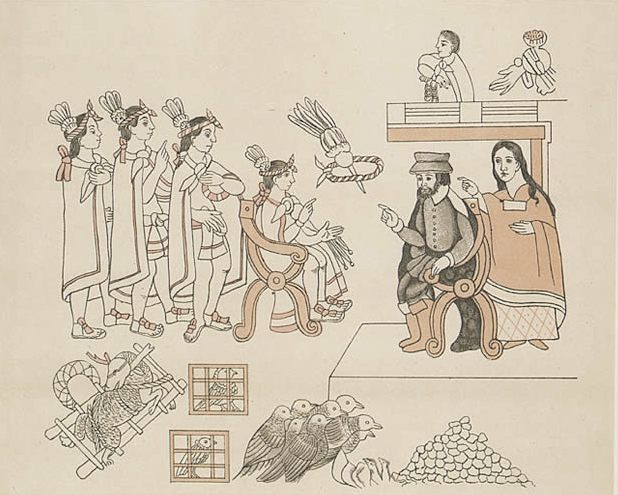

For Cortés’s first son, Martín, being the child of an explorer meant growing up without a mother. Born early in the 1520s to Malinche, an enslaved native woman who traveled with Cortés as his translator, Martín was separated from his mother early in life. Cortés made his eldest son part of the life of the Spanish Empire. He brought him to Spain and petitioned Pope Clement VII to legitimize the boy. His father’s status came with privileges: Like the Colón brothers, Martín joined the court as a page and eventually became a knight.

By then, Cortés had another son, also named Martín, with his Spanish wife. The second Martín, a noble don by birth, became his heir. When Hernán died, don Martín became the Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca and one of the richest people in the Americas. As heirs like him began to chafe against the rules imposed on them by representatives of the king, don Martín became a central figure in the fight for power in Mexico.

By the time both Martíns had returned to Mexico, in the 1560s,* tensions were rising between the crown and the second-generation heirs of the Spanish colonists, who believed they were owed a monopoly on the enslaved labor of native people. Don Martín was not the most restless among them, but he did enjoy an exalted position. The king’s viceroy had already begun to complain that don Martín “postured as royalty,” addressing nobles as if they were below him on the social ladder and forcing other elites to join his entourage when he traveled.

His downfall came in 1566, when he and other heirs put on a masquerade commemorating his father’s victory over Montezuma, staging a meeting of the two leaders and a fake fight between the two sides. At the party, according to later accusations, two brothers, the Avila boys, allegedly started making plans to crown don Martín ruler of New Spain.

If such a plan existed, it didn’t last long. Soon dozens of these second-generation colonists had been arrested, including the first Martín Cortés. The Avila brothers were beheaded and their heads left in a central plaza to rot on spikes. The first Martín was captured, imprisoned, and tortured.

Don Martín was saved by his relationship with the king. He was allowed to go to Spain and plead his case. His older brother was eventually allowed to follow him. The Martíns spent the rest of their lives in Spain, as punishment for imagining (or allowing the king to imagine) they could become a dynasty of their own. It wasn’t a hard life—don Martín was still wealthy and enjoyed himself. And they got to keep their heads.

Not all explorers’ children were seen as such threats. Some, like Sebastian Cabot—son of John Cabot, the Venetian who explored the coast of North America for the English—were explorers in their own right. Others took the wealth they were given and faded into history. Some, like the children of Ponce de León, barely escaped coups in which other Europeans took over the colonies their parents were overseeing. But some traded on their names to ascend far up the traditional social ladders of Europe.

Pizarro’s Daughter

Like the first Martín Cortés, Francisca Pizarro Yupanqui, born in 1534, had a European father and a native mother. Charles V recognized her as the official heir of Pizarro in 1537. Like Martín, she was separated from her mother early in life and was raised by a relative. When, in 1541, a rival of Pizarro’s assassinated him and took power, she was hidden away in a convent.

Her father was dead, which left Francisca Yupanqui a wealthy young woman, with a powerful name. By the time she was 15, an uncle on her father’s side had traveled to Peru and soon formulated a plan to marry her and start a new dynasty in South America. After the crown discovered this act of rebellion, Francisca was ordered back to Spain, where she encountered yet another uncle who took an interest in her and her wealth. This one she did actually marry, and together they set about consolidating the spoils of the New World their family had been promised.

In the world of the Spanish Empire, Francisca managed to rise still higher. When her first husband died, she became a wealthy widow in a strong position. She quickly remarried a man with more political power, Pedro Arias Portocarrero—who had helped found Panama, and governed Nicaragua—and joined the Spanish court. She used her wealth to build, in Trujillo, Spain, a “Palace of the Conquest,” which had a luxurious corner balcony and busts of Francisca, her father, her first husband, and her mother, Inés Yupanqui, as part of its elaborate decoration—a monument to a family and to colonialism itself, which still stands today.

*Correction: This post previously stated that the Cortés brothers returned to Mexico in the 1650s, not the 1560s, and has been updated.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook