Meet the Chef Reviving Royal Cambodian Recipes

Inspired by a trailblazing princess, Chef Nak’s cookbook is a celebration of Khmer history.

In Gastro Obscura’s Q & A series A Seat at the Table, we speak with people of color who are reclaiming their culinary heritage and shaping today’s food culture.

In 1960, Princess Samdech Preah Reach Kanitha Norodom Rasmi Sobbhana published one of the first definitive texts on her country’s cuisine. L’Art de la cuisine cambodgienne, or The Culinary Art of Cambodia, was an extensively researched, beautifully illustrated tome years in the making. It came at a pivotal moment, just seven years after Cambodia declared independence, when the nation was fighting to codify an identity beyond that of its former French-colonial rulers.

Only a few years after the princess’s death in 1971, civil war ripped Khmer society apart. The Khmer Rouge, under the leadership of Prime Minister Pol Pot, purged Cambodia’s artists and intellectuals, along with records that detailed much of what came before “Year Zero” on April 17, 1975. Copies of The Culinary Art of Cambodia all but vanished.

Nearly half a century later, Rotanak Ros, better known as Chef Nak, has dedicated her career to preserving and reclaiming thousands of years of Khmer culinary history. After leaving her position at a nonprofit organization in 2017, Ros traveled throughout the Cambodian countryside documenting recipes from home cooks that culminated in her 2019 cookbook, Nhum: Recipes from a Cambodian Kitchen.

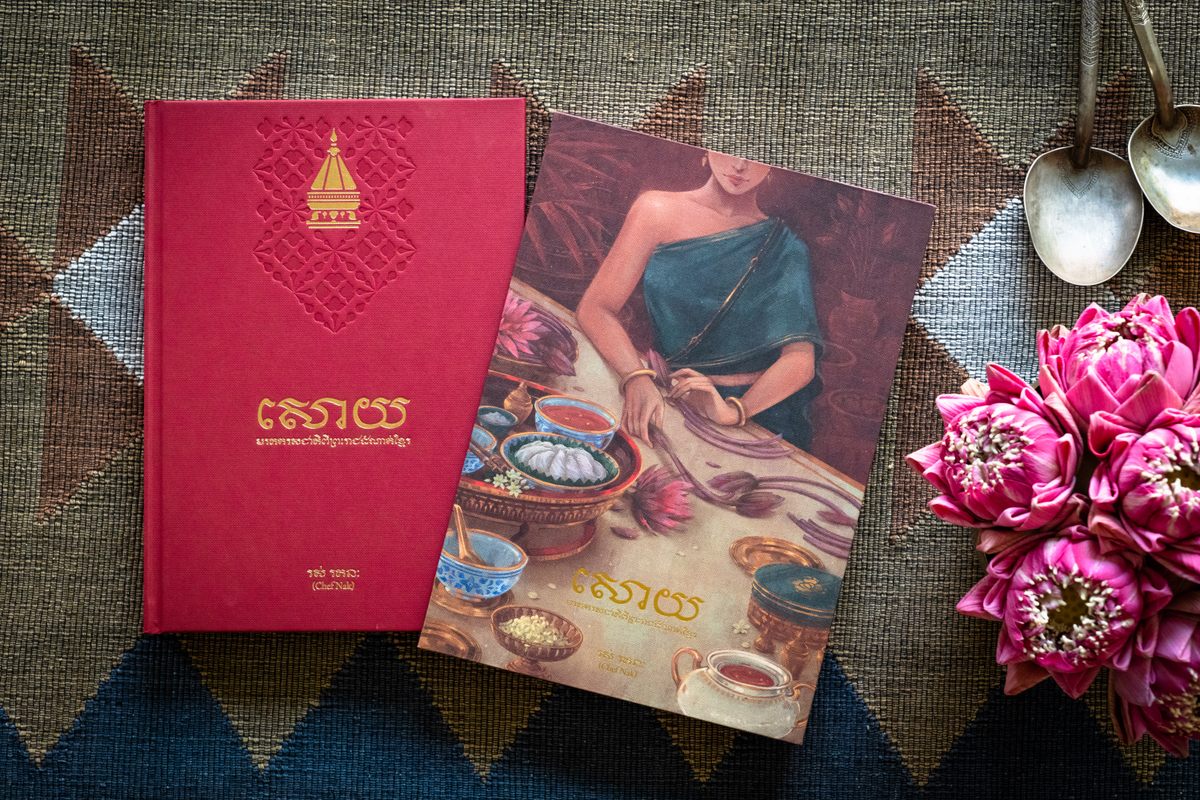

For her second work, Saoy: Royal Cambodian Home Cuisine, Ros turned her lens from home cooking to the lofty kitchens of the Khmer palace at the height of its influence. Saoy roughly translates to “dining in a royal setting” and the recipes here are the kind that might have once been served at state dinners. Princess Rasmi Sobbhana—a highly educated, fiercely independent maverick who met with President John F. Kennedy, refused to marry, and spent her life advocating for women—became something of a personal inspiration for the project. While the recipes in Ros’s work have all been thoroughly tested for a modern audience, the book is very much an homage to this powerful figure in Khmer history.

Gastro Obscura spoke with Ros about unpacking the essence of a cuisine, cooking with flowers, and the unlikely series of events that landed an original copy of the princess’s manuscript in her possession.

What drove you to shift your focus to the cookbook space?

My first cookbook came from a dream to share what I know, as well as to answer a question that I used to be asked: “What is Cambodian food?” After all these years, I still don’t have the answer, but hopefully the book helps explain some of it. It’s just so hard when you want to know about who you are in terms of what you ate if you don’t have anything to use as a reference. I thought that if I didn’t do anything about it, then the next generation of Cambodians would have nothing to show them that this is what we ate.

What inspired your second cookbook, Saoy?

A woman reached out after the first article [about my work] in The New York Times. In the email, she wrote that she used to live in Cambodia between 1970 and ’72. She was the daughter of the ambassador to Cambodia. And she remembers her mother producing a book that was written by Princess Norodom Rasmi Sobbhana. She wrote [The Culinary Art of Cambodia,] a cookbook of recipes she’d been collecting over the years from different members of the royal family. She wrote a book in Khmer and also another book in French and in English.

What do we know about the princess?

She was one of the aunties of our late king [Norodom Sihanouk]. A few things that I learned about her is that she never married. She devoted her life to lifting up women’s education, as well as to cooking and promoting [Khmer] cuisine. She really wanted to spread her cuisine to the world. She was able to do that with the support from the US Ambassador.

At that time, I thought that women in Cambodia were not taught to read or write, and I was wrong about that. But also I realized I was not the first one to start this journey to understand Cambodian cuisine. She devoted her life to this and this book is dedicated to her legacy. But it’s also a part of our culture and history.

What insights does the text offer into life in the Khmer palace?

It shows very different ways of cooking and ways of using ingredients. It also shows the influences of different cultures. So for example, in the book, Sobbhana stated very clearly that in the palace, they cooked French, Thai, Chinese, and Indian cuisines. The royal palace is a place that greets and serves people who come from other parts of the world to visit Cambodia.

Even the dancers, they danced different dances depending on where visitors came from. One of the daughters of the king, she danced more than the Khmer classical dance. She danced Mongolian, Chinese, Burmese dances depending who visited us and where she paid a visit to.

For me, I keep it the way it is, because I would like to honor the decisions of Sobbhana and also it’s part of the history. Also, I want to celebrate the differences, the varieties. No one and no culture exists in isolation. Everyone is influenced by each other.

Were there any French-colonial influences evident in Princess Sobbhana’s dishes?

A few dishes would use butter or milk to cook rice. In some recipes, instead of using cream or butter, she would use coconut cream to soak part of a baguette and then with the steamed or mashed chicken liver, then she would bake it with an egg white that had been whipped until foamy. So she would use some of the [French] ingredients and techniques, but then she would make them her own.

For example, the steamed chicken liver is very in the style of foie gras. But then she would make a sauce with fish sauce, lime juice, garlic, and a little chili. How would you imagine these two things together? But when they are with each other—foie gras is very rich and this sauce on the side is very fragrant. They balance each other out.

What was surprising to you in your research here?

For more than five years, I’ve spent most of my time, energy, and money trying to bring back the forgotten flavors of Cambodia. I’ve gone around the country talking to elderly people to try and dig out the textures and flavors that they still remember. But the process of making this book showed me that there are so many things we didn’t know about [Cambodian cuisine].

For example, I never knew that we used clove or fennel seeds or coriander in our cuisine many years ago. Initially, I thought these were international influences, but the more I learned, it’s written in very old Cambodian recipes. [Spices] had their own specific names. Like “clove” is klampu. When I first read the name in Khmer, I had no idea what klampu was. This is just one example of how what I thought I knew is small compared to what I don’t know.

In Cambodia we have a long mountain range called the Cardamom mountains, but I think at least 95 percent of Khmer don’t know what to do with cardamom. We had to journey to different parts of the country to understand Cambodian cardamom, which looks totally different from the one from India.

The other thing I learned about is that there are so many different ways of using flowers in our cuisine. So for instance, instead of using room temperature water in the cakes or desserts, Sobbhana uses rose water or jasmine water in the dough. Things could be very simple, but they make it in a way that’s on another level.

What is one recipe that stands out to you from your research?

There’s one recipe for “white pearl soup.” It tastes almost like congee, but it’s made with tapioca pearls. That soup really stands out in my mind. It’s very much comfort food. It looks simple, but there’s a lot of work behind it. The broth takes five or six hours to make.

That brings up a good point: Since these recipes were written for royalty, just how complicated are they?

Some soups can look very simple, but just the process of making the paste can take four people three hours to make. The paste contains 15 different ingredients that have to go through being thinly sliced, then sun-dried, then pounded, then sautéed again.

Of course, in the palace, they had people there to prep for the cooking. And I think that’s what makes it different from our day-to-day cooking. According to Ambassador Julio [ A. Jeldres], who was very close to our late king, who wrote one of the forewords in the books, everything needed to be prepared properly and took a lot of time.

Why does it feel so important to you to correct the narrative of what Cambodian food is? Why do you want the world to know about some of these recipes?

We as a people are struggling to really accept who we are. To know that these kinds of ingredients are being used here and there—we used to think we were copying this or that other country, but we had that knowledge a long time ago. It’s a fight that I have to fight. But it’s also a fight that is worth it to reintroduce these ideas and ingredients back.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook