From Indonesia to Ingonish, Some Bones Won’t Stay Buried

As seas and storms erode coastlines, cemeteries are giving up their dead.

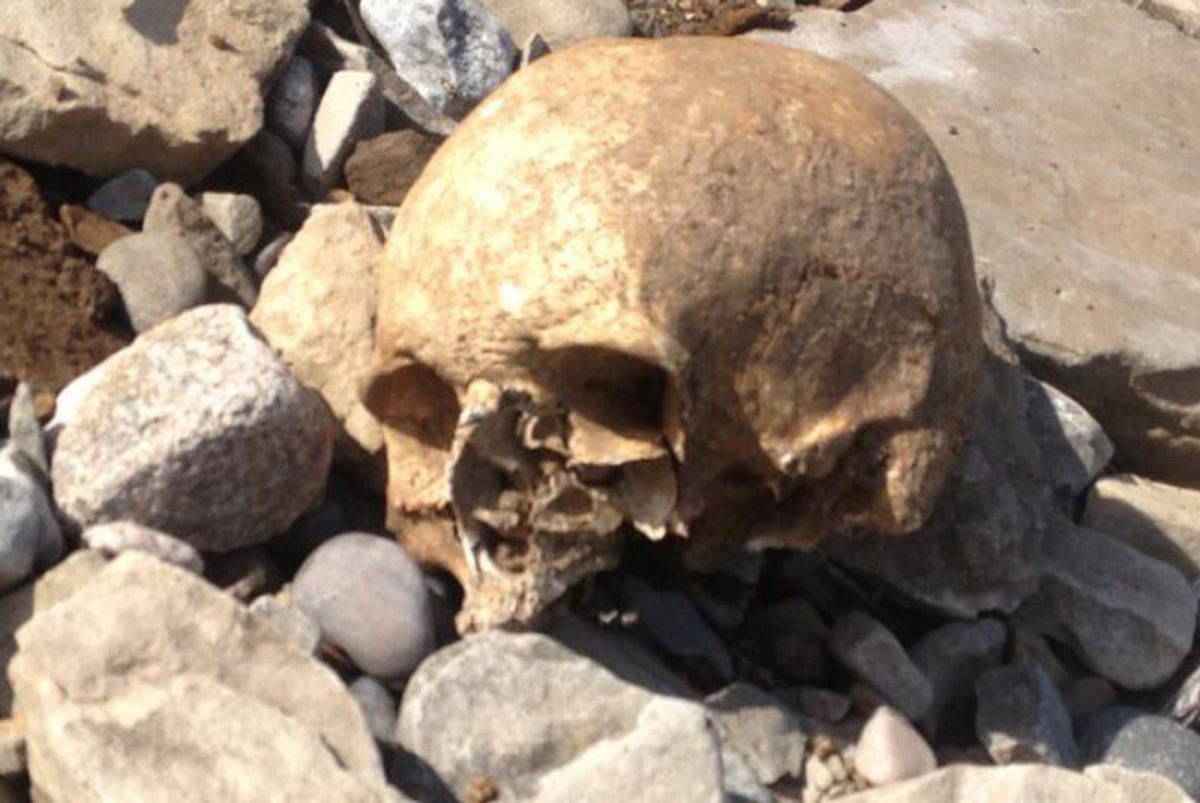

A skull drops into the sea in Nova Scotia. A femur juts out of a stream bank in Texas. A coffin breaks through the soil in New York. A fisherman nets a tombstone off the coast of Virginia.

So much for eternal rest. Cemeteries around the world, especially coastal plots, are losing the fight against the elements as seas, storms, and floods ravage once-stable soils, leaving human remains strewn in their wake.

“We have a long-standing battle with the sea,” says Hector Murphy, longtime caretaker of a church cemetery, some 200 years old, hovering on a cliff in Ingonish, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. For decades rising waters near this fishing village, on the famed Cabot Trail, have been chewing on the land—high craggy faces and soft sandy shores alike—and spitting out its bones. Walking the beach below the church’s high perch, Murphy himself has found skulls and other skeletal remains scattered in the sand.

“These people were buried well back from the shoreline, but the water has moved in at least 100 feet,” he says. Little is known about the interred there—cemetery records were lost in a fire years ago. With no funding to shore up the site, “it’s upsetting, but there’s nothing we can do.”

Some 350 miles down the Atlantic coast, a cemetery at Rochefort Point, at the famous 18th-century Fortress of Louisbourg, has gotten more attention: Scientists there are excavating and moving remains before the sea washes them away. To help make sure they accomplish this mission, Amy Scott, a bioarcheologist at the University of New Brunswick, has turned the effort into a multi-year field project for her students.

So far, teams have relocated 104 bodies—they’ve had to sift through mixed bones, as unmarked plots were sometimes inadvertently reused—but there may be 1,000 still interred. “There’s a lot of information already about this historic place,” Scott says. Now, its bones are helping “tell the stories of the everyday people who lived here.”

Scott says that while she can’t ID particular people from remains, bones offer enough general information for a snapshot of their lives. For instance, “here’s a woman who died in her 30s. She has certain markers that tell us what she ate, that she did heavy labor, and that she grew up in southern France.”

Remote seaside towns aren’t alone in their grave troubles. In a cemetery near Buffalo, New York, last spring, a mother who went to visit the grave of her son discovered him missing. Shifting soils and a collapsing hill had forced officials to relocate more than 100 coffins, including her son’s, to more stable plots. “Do you know how sad that is to come on Easter and have your son’s grave look like this?” she said to Spectrum News.

Yet coasts are particularly vulnerable, with storm surges joining rising waters for a one-two punch. “It’s a bit macabre,” says William Neal, emeritus professor of geology at Grand Valley State University. “But when these storm events occur and groundwater levels rise, coffins can burst forth from the ground. Not the resurrection expected!”

Consider Louisiana’s grave upheavals during Hurricane Katrina, when flooding sent nearly a thousand coffins and vaults floating along the Gulf Coast, some for miles, scattering skeletal remains hither and yon. Identifying the displaced was a logistical—and emotional—nightmare. One resident told the New York Times that he discovered his grandmother’s remains disinterred, still in her pink gown. Another whose family was affected told reporters it was vital that these lost souls go back underground. “The problem,” he said, “is trying to figure out how to put them back together.”

“Cemeteries by the sea are classic examples of how humans erroneously accept that nature [is] static,” says Neal. Even without rising waters, “normal coastal erosion would cause shoreline retreat. But sea level has been rising [for some 8,000 years] since the Ice Age ended and the glacial ice caps melted.” It was rapid initially and then slowed, he says, “but accelerated again in the late 19th or early 20th century. While some people on low-lying coasts may not have alternatives for burials, “others do have a responsibility not to ignore Nature.”

Coastal communities represent more than a third of the global population. According to the UN, over 600 million people (10 percent of the world’s population) live in coastal areas that are less than 100 feet above sea level, while 2.4 billion (a little less than 40 percent) live within 60 miles of a coast. While coastline recession is widely variable from place to place, it can be 25 or even 50 feet per year. In the U.S., at least 40 percent of coastlines are suffering significant erosion. In some spots the land, and whatever is on it—or buried in it—is melting away like ice.

Over in Great Britain, St. Mary’s Church graveyard, in Whitby—the inspiration for a scene in Bram Stoker’s Dracula—began giving up its bones in 2013, after heavy rains contributed to a landslide. Bones that tumbled from the cliff were collected and reinterred, but cracks at the top continued to form. Engineers worked to stabilize the cliff—with netting, soil nails, and drainage—but natural forces will continue to threaten the famous site.

In a coastal village cemetery in Thiawlene, Senegal, not far from Dakar, graves are packed in tight, their tombstones jumbled and crumbling. Families there have stacked cinder blocks atop plots in a futile attempt to keep remains in place. Kids on the beach play with the human bones they find, as entire tombs are swept away by the unstoppable sea. Meanwhile, the Senegalese government estimates that 50 percent of its coastline is at high risk of destruction from the rising sea and increasing storm surges.

Back in the U.S., scientists have found a (relatively) bright side to all this dark news. Dated grave markers can help them measure the ocean’s expanding reach. Along the Eastern Shore of Maryland, tombstones discovered in salt marshes offer time-stamped evidence of rapid shoreline retreat. Joe Fehrer of The Nature Conservancy is studying a small family cemetery in the Robinson Neck Preserve on Taylor’s Island, Maryland, where markers indicate burials took place from 1818 to 1851.

“This area was once on relatively high wooded ground”—probably at least 1.5 feet above the water, he says. Now, water sloshes over his boots as he hikes in. To reach the spot and avoid sinking into the marsh, he recently had to reroute twice. “So much of this region is being inundated,” he says. “We’re losing a lot of cultural history as these cemeteries—entire communities—go under water.”

Changes in the landscape can signal where losses will occur next, he says, such as sites “where high marsh grass is thriving where it wasn’t before.” Another sign: the appearance of “ghost forests,” which appear when rising groundwater, often salty, kills a stand of trees. As the grove topples, any graves beneath it are exposed.

“Especially in low-lying areas,” Fehrer says, “it’s not uncommon now to see a burial with a heavy concrete lid so the casket doesn’t pop out of the ground in a storm or flood.”

A longer-term fix is to move remains—as people have done throughout history. At Louisbourg, for example, Amy Scott says a number of cemeteries were relocated during the outpost’s active years, in the 1700s. For modern cemeteries still in use, families whose loved ones are unearthed say they expect reburial in more permanent plots.

Engineers do have ways to bolster hillsides and slow erosion. On Hart Island in New York, the bodies of more than a million New Yorkers—people who were poor (and often HIV-positive) in life, or whose corpses were unclaimed at death—are interred in a still-active public cemetery (the largest in the country). Officials there have promised to reconstruct the eroding shoreline to stabilize graves that have been losing bones to the Long Island Sound. (Bones recovered from the shores are now being reburied—by Rikers Island inmates.)

But hardscapes such as seawalls, which deflect wave energy instead of dispersing it the way natural shorelines do, are often prohibitively costly. They’re also usually temporary solutions as nature continues to work against them.

Nobody knows how many village and family plots, how many unmarked mass graves—of soldiers and slaves, of prisoners of war and the poor—remain along the edges of North America and around the world. But especially in places where there’s no one left to claim them, the dead face continued disturbance.

Where moving isn’t feasible, says Fehrer, “the best we can do is document these places, these people, with the realization that at some point it will all be history.”

Neal, too, advises a practical approach to these vulnerable sacred grounds: “Move [them], or let [them] fall in,” he says. “But don’t waste resources trying to hold back the sea.”

Because the sea keeps on coming. Rising waters lap at the fence of an 18th-century Maori graveyard in the Coromandel Peninsula that’s still in use today. At high tide, the sea threatens the remains of many elderly people and children who were victims of disease epidemics, plus members of local families more recently interred. Decades ago there was talk of building a seawall, but nothing came of it. More recently, families have started debating whether to move the dead before it’s too late.

“I hear them calling,” a local woman told a reporter for Teaomaori in 2017. “I hear them saying, do something.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook