The ‘Christmas Tree Boat’ Shipwreck That Devastated 1912 Chicagoans

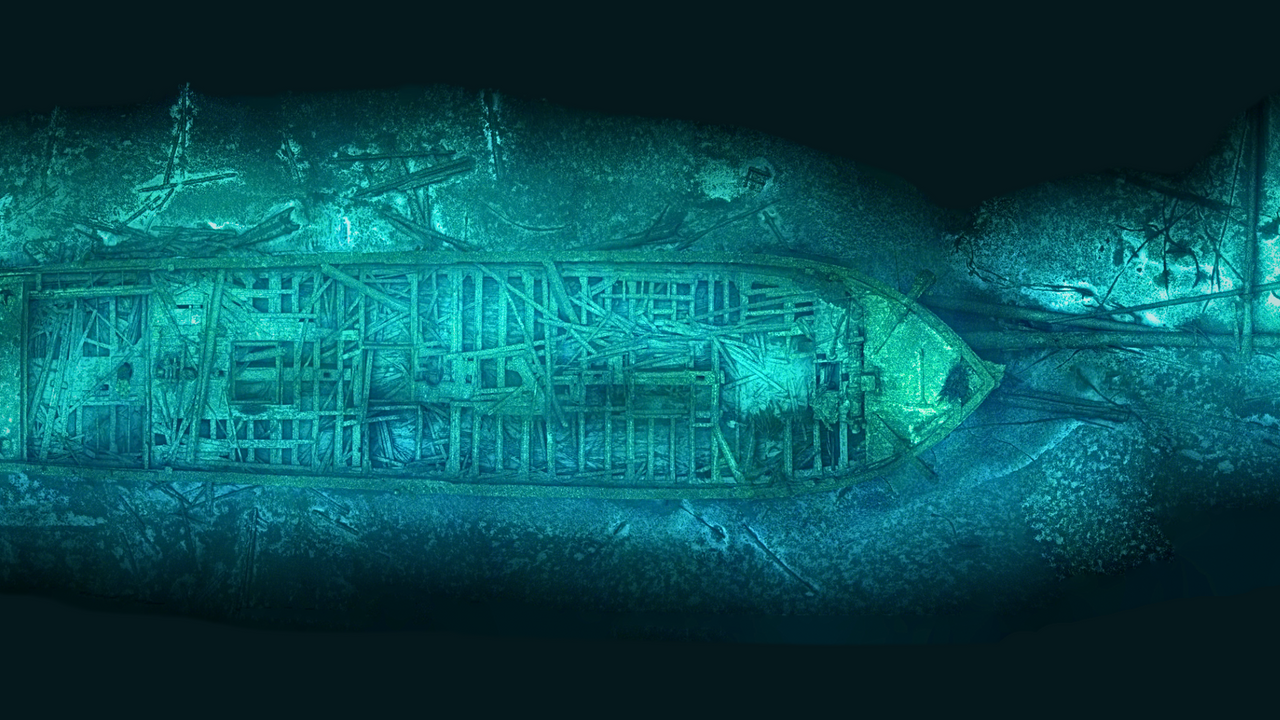

Marine archaeologists are beginning to understand what really happened to Captain Santa’s ill-fated ship.

On November 23, 1912, the storm sweeping down from the north had ships running for cover throughout Lake Michigan—among them, a three-masted schooner, the Rouse Simmons, filled with thousands of evergreens. Having harvested its load from the coniferous forests of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, the Rouse Simmons was eagerly anticipated at its regular berth along the Chicago River. But with no sign of the ship by Thanksgiving, five days later, families of the crew began to fear the worst.

Reports soon reached Chicago of a distressed but unidentified schooner, spotted on the 23rd, seen limping its way along the Wisconsin coast. By December 4th, the city woke to heart-wrenching reports of orphaned trees washing up onto lakeside beaches, driving local anxiety to a fever pitch. A crew member—who had refused to board the Simmons in Michigan for its return south—had since traveled to the booming city by train, and contacted the papers with haunting claims that the vessel had been overloaded and unfit to sail: “RATS FLED DOOMED XMAS SHIP,” the banner headline read. Holding out hope that the boat had simply run aground while seeking safe harbor, the search for survivors continued for weeks. A December 5th edition of the Chicago American, however, did not mince words. “LOST HOPE FOR SHIP,” it blared. “SANTA CLAUS BOAT LOST.”

A century later, the Great Lakes are no longer a marine thoroughfare for schooners and barges loaded with Christmas trees. Today, an apocryphal legend of the Simmons endures, a touching maritime tale of adversity and holiday goodwill. Since 2000, the U.S. Coast Guard has followed the Simmons’s path in a modern vessel loaded with evergreens. They do so in honor, not just of the ill-fated schooner, but of Herman Schuenemann—the enterprising mariner known as “Captain Santa,” who made the “Christmas Tree Ship” a legend.

By 1912, masted sailing vessels like the Simmons often carried as much nostalgia for a bygone era as they did cumbersome cargo. By the Civil War, the schooners’ heyday had passed, with many former workhorses finding themselves stripped of their masts and tethered behind steam-powered barges in a single, dilapidated chain that could stretch a mile.

The Simmons had only recently found itself pressed into service as Captain Santa’s floating, evergreen-toting sled. First-generation German-American Herman Schuenemann had bought a share of the vessel in 1910, having taken over the conifer-trading mantle from his elder brother, August (who had himself gone down with a former Christmas tree ship, the schooner S. Thal, in 1898).

In the decades leading up to the Simmons demise, Christmas had become a booming industry. By the 1890s, Chicago’s flow of German immigrants—a group whose Teutonic roots helped introduce the Christmas tree to American shores in the first place—peaked. At the same time, the country’s burgeoning middle class seized upon Christmas as a testament to their success. The holiday was an opportunity to showcase a bounty unthinkable to their forebears.

Into this consumerist spectacle stepped the brand-savvy Herman Schuenemann. Rather than wholesaling trees through city retailers and middlemen (many of whom received their trees by train), Schuenemann’s vessels would set up shop directly downtown, under the Clark Street Bridge, where Chicagoans could purchase Michigan evergreens straight off the boat for a dollar or less.

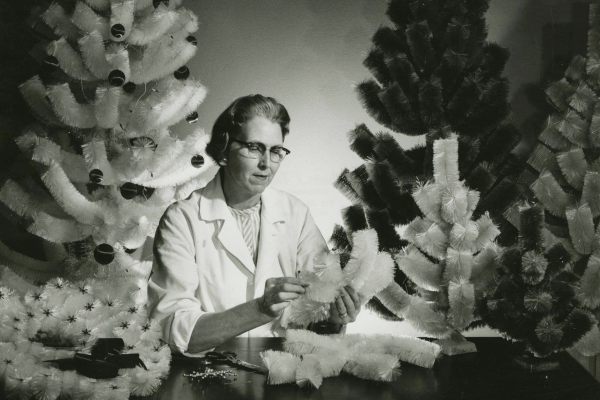

Newspapers would speak of “a score of girls and women”—Schuenemann’s wife and daughters among them—weaving garlands and wreaths on deck. It was as if the ship was part of Santa’s floating workshop. Though lacking the belly of his namesake, Herman Schuenemann was more than happy to step into the ready-made position of Chicago’s “Captain Santa.”

While standing on the ship’s bridge, a pipe-puffing Schuenemann said, “Christmas trees are going to be high this year,” while being interviewed for a December 9, 1909, profile in the Chicago Inter-Ocean. “This is the 23rd trip I’ve made up into pine country for Christmas trees,” Schuenemann said, “and it’s the slimmest cargo I ever brought away. Many a poor little kiddo in Chicago will have to go without his Christmas tree this year because his Santa Claus won’t have the price to buy one.”

Schuenemann’s business acumen, however, had its downfalls. To transport his bulky cargo, he opted to purchase larger vessels that often could only be afforded due to their age and disrepair. Schuenemann also had his share of competitors in a finite and fleeting market. These tight margins may have driven Schuenemann to take a gamble in the notorious Lake Michigan weather on that fateful November in 1912.

“Captain Santa was a two-fisted capitalist,” laughs Tamara Thomsen, an underwater archaeologist for the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Despite being a proud descendant of Wisconsinites, Thomsen never heard the tale of the fabled Christmas tree ship during her childhood in Indiana and Maryland. The legend goes that rescuers spotted the ship, only for it to disappear from view into a raging blizzard. Some tellings mention a message in a bottle purported to be Herman Schuenemann’s last words and a distressed little girl waiting for Captain Santa to dock at Clark Street Bridge in Chicago.

After taking a job in 2004 as a maritime archaeologist for the State of Wisconsin, Thomsen knew full well just how much the beloved legend circulated among aficionados of Great Lakes history. She reckoned that a proper archeological study could make a huge public impact.

“Everyone wants to hear the story. No one likes to hear my end of the story,” says Thomsen, one of the authors of the first-ever archeological survey of the Rouse Simmons resting place, about 10 miles northeast of Two Rivers, Wisconsin. According to primary sources Thomsen uncovered, the Simmons likely never sank amid an evening blizzard; a call into the Two Rivers Lifesaving Station arrived in the mid-afternoon before the snow began to fall. Similarly, records of the rescue efforts indicate that the life-saving vessel never glimpsed the distressed Simmons, suggesting that it likely sank before their arrival.

“I get a lot of groans when I change the ending,” Thomsen ruefully admits.

After a Milwaukee scuba diver discovered the wreck in 1971, the remains of the Simmons quickly attracted a slew of underwater tourists (including a visit in 1973 that recovered its starboard anchor, which has since spent the past half-century adorning the entrance of the Milwaukee Yacht Club).

In waters barely above freezing, Thomsen and the rest of the archeological survey team scoured the wreckage for clues about the ship’s final moments. A pile of anchor chain, still visible on deck, suggested that the crew had been preparing to deploy the anchors while still in open water.

After returning to the wreck site in the summer of 2007, Thomsen and fellow archeologist Keith Meverden successfully located the Simmon’s long-lost port anchor, almost two hundred feet north of the ship’s main hull. Dropping anchor in stormy waters is as dangerous as it sounds. Historians suspect the act may have been a desperate, last-ditch attempt to steady the vessel enough to deploy the lifeboat.

And the tale of a message in a bottle from a doomed captain? It was almost surely a hoax that Chicago newspapers amplified. And while some trees did find themselves pulled up in fishermen’s nets, much of the evergreen cargo never washed ashore—another part of the apocryphal legend. In fact, many trees remain securely in the ship’s hold. Some are so well preserved—snug in Lake Michigan silt—that they still have their needles.

Also surprisingly intact: Captain Santa’s bound oilskin wallet, discovered in April 1924 ensnared in the nets of the fishing tug Reindeer. The wallet contained not only Schuenemann’s business card, and expense receipts for the trees, but clipped newspaper articles about his exploits as “Captain Santa.”

The little girl waiting for the Christmas tree ship may be another bit of truth in the legend. The 1998 obituary for Ruth E. Flesvig, a retired public school teacher, reported that she finally received her much-delayed tree delivery at the “Rouse Simmons Christmas Tree Reunion Party” in 1990.

Historically sound or not, the legend perseveres among Great Lakes mariners. In the summer of 2000, some sailors found themselves aboard the United States Coast Guard Cutter Mackinaw as part of “the Mac,” an annual 333-mile yacht race from Chicago to Michigan’s Mackinac Island. Conversation turned to the Simmons, and how a modern recreation might keep the story alive.

Later that same year, the World War II-era icebreaker Mackinaw embarked from its home port of Cheboygan, Michigan, at the very northern tip of the state’s iconic mitten, with a load of over a thousand Christmas trees from a Manton, Michigan, tree farm.

The U.S.G.C.C. Mackinaw has been making its Yuletide trip ever since. These days, however, the Mackinaw looks a little different—in 2006, the Coast Guard decommissioned the original Mackinaw and replaced it with a smaller, more modern vessel of the same name. The ship still shuttles its Christmas cargo in a race against Midwestern winter as it makes its way south through Lake Michigan to Chicago’s Navy Pier, all while simultaneously hauling up navigational buoys for seasonal maintenance.

The weather that once imperiled Great Lakes mariners still earns its reputation: en route to Chicago this year, the Mackinaw had to navigate a storm that coated the ship’s deck in ice. The ship’s more modern duties can sometimes get tangled up with the history that lines the bottom of the Great Lakes: The Mackinaw had to make a pit stop to return an anchor of another wreck, the Kate Kelly, after the artifact had been “unintentionally recovered” while pulling up a buoy.

“It’s hard not to feel connected to the legacy of ships on the lake,” Mackinaw Captain Jeanette Green later said in a satellite phone interview with “Bob’s ‘No Wake Zone’,” a sailing-themed radio show broadcasting from Lake of the Ozarks, Missouri. “[But] we have so much more safety than those sailors did.” The vessel dropped a memorial wreath directly above the site of the Simmons shipwreck.

Drifting into Navy Pier on the first Friday of December, the Mackinaw unloaded its evergreens over the weekend amidst performances of Christmas carols, Marine Corps hymns, and sea shanties from the Coast Guard Academy glee club. Other commemorative events included a cannon and horn salute and public tours of the vessel. In partnership with local organizations, the trees then find themselves trucked across Chicago, toward their waiting holiday homes: Purchased by funding from private donors, every tree is given away to pre-selected families at no cost.

“It’s not just the Mackinaw,” Tamara Thomsen clarifies. “It’s done also in Toledo at the National Museum of the Great Lakes,” she says. “There are a lot of places that celebrate this tradition [of delivering Christmas trees on the Great Lakes]. It’s pretty cool to bring us back to our maritime past, this culture that used to be really important for these communities.”

“This weekend, I’m going up to Manitowoc,” Wisconsin, Thomsen adds. “They do a [Christmas Tree Ship] recreation,” she says. “I may dress up as Mrs. Claus, and ride on the ship. That’s my thing now.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook