You Probably Share Your Home With at Least 100 Kinds of Bugs

And cleaning more often won’t change a darned thing.

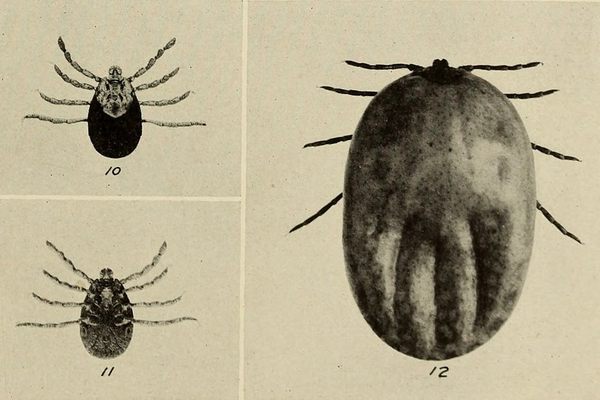

Long before humans had pets or roommates or any other beasts of questionable hygiene sharing their homes, we lived with bugs. The average household has around 100 species of arthropod, happily passing their days: centipedes in your storage area, booklice in your books, cockroaches literally … wherever. But it’s only recently that scientists have begun to understand how the physical attributes of your home can make it more, or less, hospitable to insects, arachnids, diplopods, and others. Basically, if you live in a ground floor apartment, with carpet and windows, and you wear shoes inside, you might as well have invited them in.

“We are just beginning to realize—and study—how the home we create for ourselves also builds a complex, indoor habitat for bugs and other life,” Misha Leong, lead author of a study on the topic published this week in Scientific Reports, said in a statement. To investigate what arthropods look for in a home (besides natural light, energy-efficient appliances, and location-location-location), scientists surveyed 50 homes in Raleigh, North Carolina. Carpeted rooms attract a much wider variety of insects than those with bare floors. Anything that contributes to “indoor-outdoor flow” (say, a door) is similarly appealing.

You might think, “Oh, but we’re very tidy here,” but cleaning makes little difference. Only cellar spiders favor cluttered spaces—the others simply don’t care. And Fido, or your affectionate houseplants, also don’t make a difference one way or the other. On top of that, the study shows, you’ll find different invertebrate communities in different rooms of the house. The living room, it turns out, is for living: booklice, fruit flies, and ladybugs will happily spend their days there. Bathrooms, kitchens, and bedrooms have less diverse clienteles. Deep in the basement, camel crickets vie for space alongside ground beetles and many-legged millipedes.

The thought of creepy-crawlies burrowing through your shag may seem gross, but bugs, in a roundabout way, might be making you healthier, Michelle Trautwein, one of the study’s authors, said in a statement. “A growing body of evidence suggests some modern ailments are connected with our lack of exposure to wider biological diversity, particularly microorganisms,” she said, “and insects may play a role in hosting and spreading that microbial diversity indoors.”

In short, every room is an ecosystem, a collection of ecosystems, in fact. Predators stalk prey, scavenger beasts scramble for scraps, and grazers consume whatever they can find—wild ecological dramas playing out on levels we rarely see. “We’re learning more and more about these sometimes-invisible relationships and how the homes we choose for ourselves also foster indoor ecosystems all their own,” said Leong.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook