How North American Bison Ended Up in the Swiss Alps

The mammals in Geneva’s outskirts are now iconic in the country.

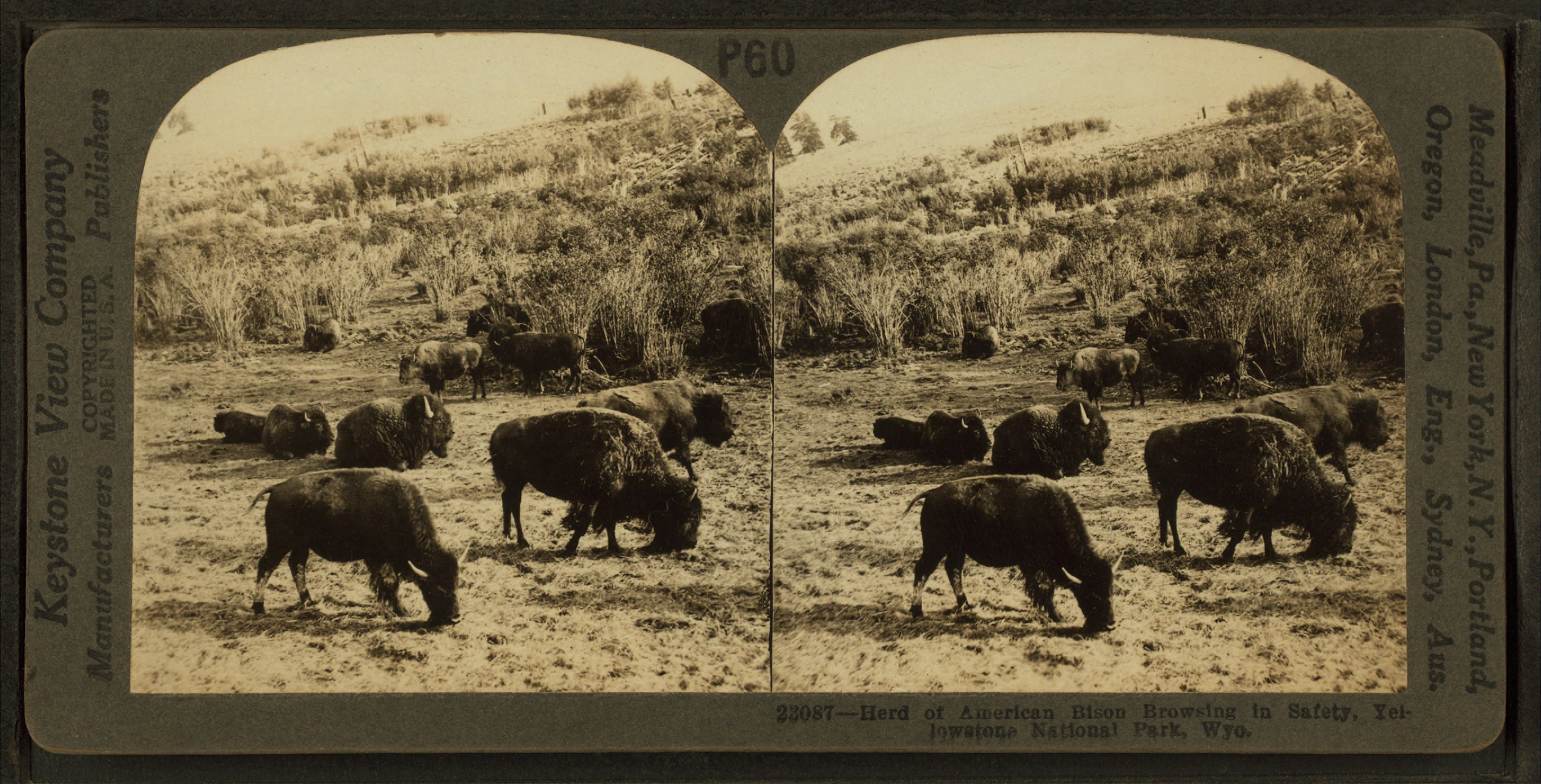

On the drive from the airport into Geneva, Switzerland, you may spot creatures roaming the fields that seem out of place. The hulking figures are too large to be the archetypal cows of the lush Alpine meadows, they’re far more agile, and they sport large humps on their backs. They look eerily similar to North American buffalos, and with good reason: They are the very same animals. But how did they find their way to the Swiss Alps?

Years ago, a young man from a Swiss farming family, Laurent Girardet, ventured to Alberta, Canada. He went to participate in an exchange program, work on a farm, and learn English. During his time there, he unexpectedly fell in love with the bison (the term “buffalo” is often used interchangeably, but in Switzerland they are known as bison, as their scientific name is Bison bison). “I always liked big spaces and everything related to bison,” Girardet says.

He also liked the idea of raising animals naturally—that is, on pasturelands rather than in enclosures, and on a grass diet rather than one bolstered by antibiotic supplements. Compared to Switzerland’s domesticated cows, bison were robust and healthy, too. So he resolved to raise them instead. “We decided to walk away from traditional dairy cattle, to turn ourselves to something more natural and extensive,” he adds.

When Girardet first shared his plan to sell his cattle herd and replace it with bison, his fellow farmers thought he had lost his mind. No one had ever tried to raise these animals in Switzerland. What’s more, no regulations existed for bison farming, nor for the imports necessary to sustain them. Girardet’s paperwork for the unusual cargo especially confused authorities. “Getting the Swiss authorities to sign off on importing bison was quite a tough job,” he recalls. “It was the first time someone wanted to import bison for another purpose than putting them in a zoo.”

Still, Girardet pressed on. He travelled to several United States ranches in South Dakota and Wyoming, and to a buffalo stock show in Denver, to choose the bison. Once he bought his initial stock in the early 1990s—several ten-month-old calves—they were in for a long journey. First, the bison travelled to Wisconsin to go through a quarantine. Then came a long flight from Chicago to Zurich. From there, they traveled to Geneva on a truck, and then arrived in the Alps.

Today, Girardet owns a herd of 150 bison, and 35 to 40 of those are butchered every year. Calves are born every spring, he says. Behind the wire fence where he stands, a young, light brown-tinted calf nuzzles on its mother. Girardet—who is tanned and lean, with a mop of salt-and-pepper curls—extolls on how bison are easier to care for than cows. They are sturdy, healthy wild animals that rarely get sick, and don’t have to be corralled for winter, either. Bison eat grass in summer and hay in winter, as opposed to cows, who are often fed grain, corn, or soy to fatten them up.

It may not come as a surprise to learn that many meat connoisseurs believe that bison cuts are much tastier, more nutritious, and higher in omega-3s than their beef counterparts. “This is simply because grass is high in omega-3s,” Girardet explains. “As herbivores, grass should be their sole nourishment. Corn, soy, growth hormones, and antibiotics should be out of the picture.”

While bringing bison all the way to Switzerland proved challenging, his efforts weren’t all for naught. Bison meat quickly became popular fare, and its place in the country was cemented when other farmers began buying Girardet’s animals for their own farms. From there, the bison migration through Switzerland continued (and continues to this day). “All bison raised in Switzerland come from our herd,” Girardet says.

Christian Lecomte, who owns the Bison Ranch in Les Prés-d’Orvin, about 100 miles north from Geneva, bought several animals from Girardet shortly after they first set their hooves on Swiss soil. At first, Lecomte set out to diversify his offerings and become more competitive in what he felt was a saturated market: Sure, his cows produced a lot of milk, but so did everyone else’s cows. But given his location in the mountains, and the fact that he had plenty of pasture, he thought breeding bison would work well. Lecomte’s herd is smaller than Girardet’s—he has 15 female bison, which bear 12 to 15 calves a year.

But over the past 25 years, Lecomte’s bison have also become a full-fledged tourist attraction. People travel from all over the world to see them roam, and to taste bison meat. The restaurant on Lecomte’s farm serves a wide range of bison dishes, including bison filets, entrecote, and fireplace-roasted steaks. For those who want to take some bison home, he sells bison salami and bison terrine.

On top of that, bison are symbolic creatures, he says, as people know and love them from movies and documentaries, particularly those set in North America. (In the United States, bison have a far more contentious history— they have been a crucial part of life for Native Americans residing in the Great Plains regions, but risked extinction in the 19th century, when settlers slaughtered millions of them.)

Michel Prêtre, of Jura Bison, located about 130 miles north of Geneva, began raising bison more recently. Back then, it was more precarious to raise cows, given the threat of an impending epidemic. “There were a lot of problems due to the mad cow disease,” he notes. So he sought alternatives. He brought 13 bison over from Geneva in 2004, and later six more from the United States. Despite their might and wild temperament, he believes that bison are simpler to care for than cows. “It’s easier to raise bison because they don’t need as much care and maintenance as cows,” he notes.

His farm is popular not only with tourists, but also with local schools, which organize frequent visits. Prêtre sells about half of his meat to local restaurants and distributors, and uses the other half on his farm. During summer barbecue season, he serves steaks, roasted bison sausages, and various tasting selections, as well as bison burgers for kids. People enjoy bison meat so much, he says, that it’s hard to keep up with demand.

Compared to beef, bison meat is still a relatively niche product in Switzerland. It’s not available in supermarkets, and it’s not everyday fare. Raising bison itself is still a slow-growing practice, too, given that bison farmers need a lot of land. Still, the bison’s popularity has benefited from consumers’ interest in humane and sustainable ways of raising animals, Girardet says. “Every bovine should pasture in a spacious grass field, without being fattened in feedlots or undersized paddocks,” he says. “We consider ourselves lucky to be raising such amazing animals, which underwent no selection or genetic manipulations from the hands of men.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook