Found: Ancient ‘Ghost Dunes’ on Mars

There might be surprises inside.

It’s not a great idea to sunbathe on Mars. But if you really wanted to, and you lived a few billion years ago, we now know where you might have gone. In a recent study in the Journal of Geophysical Research, planetary geomorphologist Mackenzie Day and astrobiologist David Catling announced their discovery of about 800 “ghost dunes”—the imprints of ancient sand piles—clustered in two different locations on Mars. Examining these former dunes can tell us more about the red planet’s historic climate, and might contain more surprises as well.

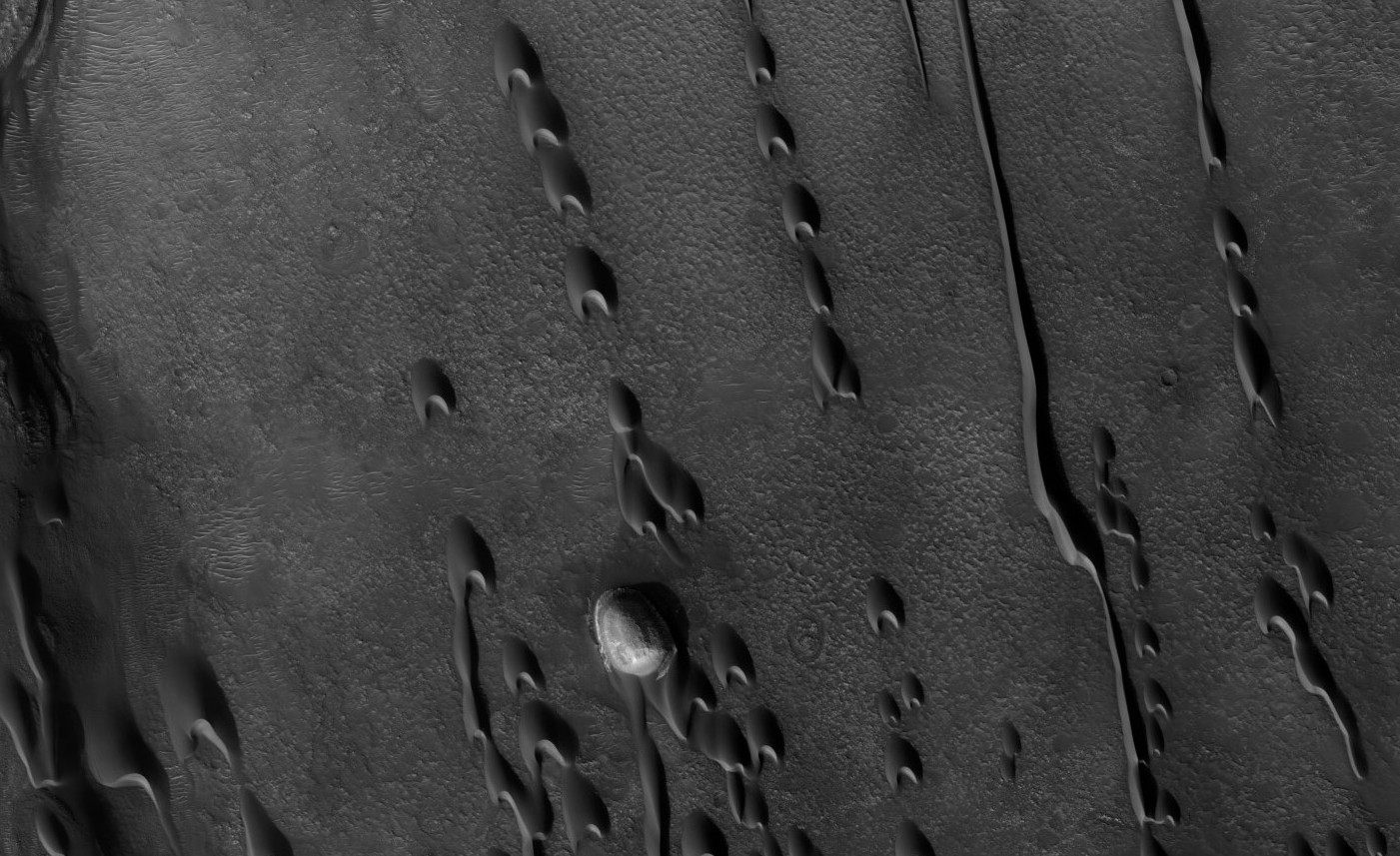

As Liza Lester explains at the American Geophysical Union’s GeoSpace blog, when the dunes formed, Mars was a little more exciting, with flowing water and active volcanoes. About two billion years ago, streams or lava flows began covering the dunes with sediment, which hardened around them like a mold. Then wind blew the sand away from the inside, leaving an empty shell behind—a “ghost dune.”

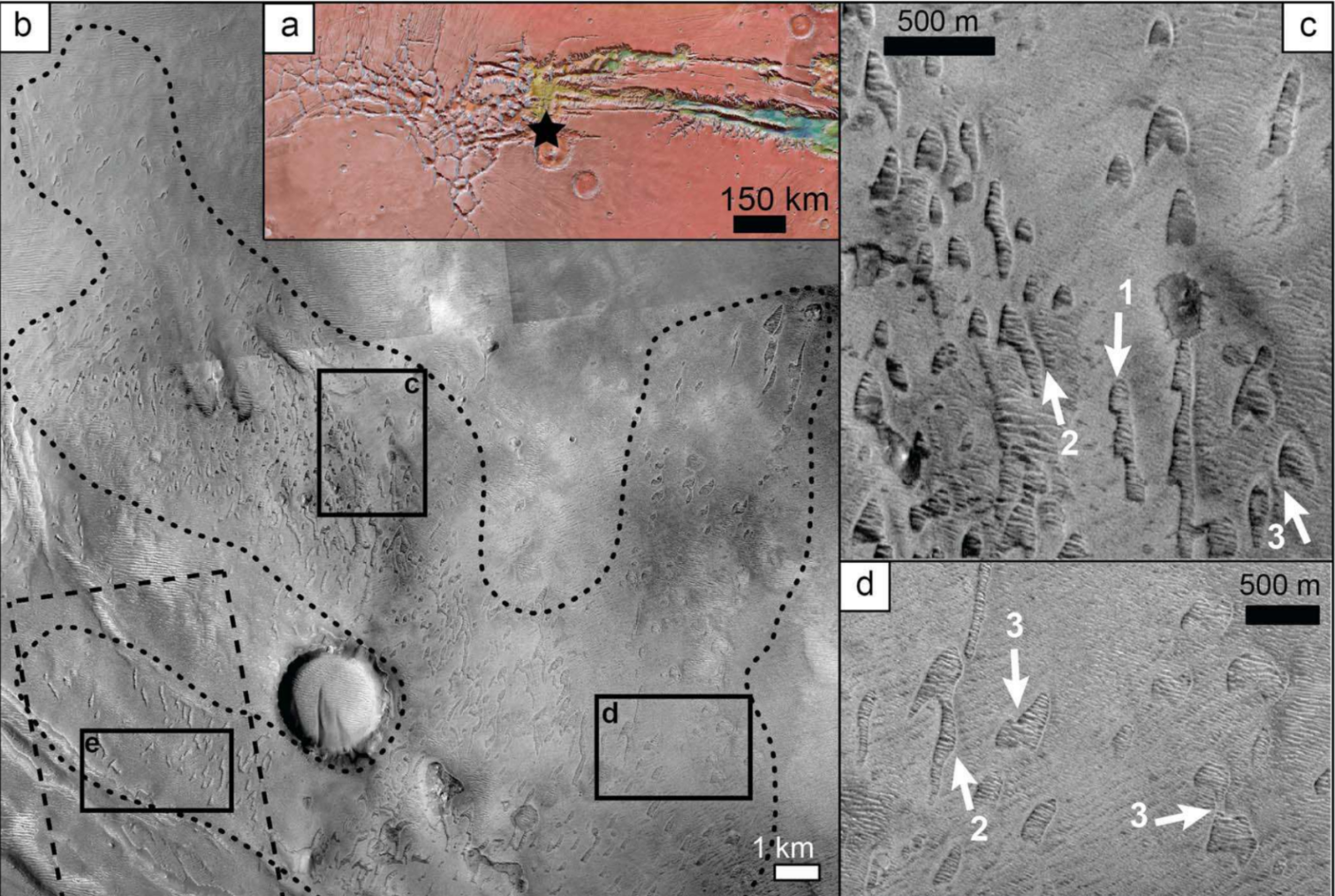

On Earth, you can find ghost dunes in the Snake River Plain, in Idaho. (They date back to the late Pleistocene.) They have also been spotted on Mars before: there’s a really good field near the Medusa Fossae formation, for example. In this new study, Day and Catling identified about 300 previously undiscovered ghost dunes in the Hellas Basin—a 1600-mile long impact crater that also boasts volcanic flows and canyon systems—and nearly 500 in Noctis Labyrinthus, a mazelike tangle of steep valleys.

They found them by examining images of Mars’ surface for clusters of crescent-shaped pits, “aligned like croissants on a baker’s tray,” as Lester puts it. This particular shape indicates that the dunes were “barchan dunes,” which form on flat surfaces in unidirectional winds.

By taking note of the dunes’ orientation, the researchers were able to figure out which way the wind was blowing. In both cases, it was coming from the north, and slowly pushing the dunes south—different than the winds there today. This indicates that the environmental conditions on Mars have changed over time.

By comparing these ghost dunes to existing Martian ones, the researchers were also able to size them up. They found that the Hellas Basin dunes averaged around 250 feet tall, while the Noctis Labyrinthus dunes were about half that.

If we’re really lucky, the dunes might be able to tell us even more about the ancient landscape. As Day and Catling point out, it’s possible that the wind didn’t manage to completely clear out the molds. In that case, some ancient sand—and whatever it contained—might still be stuck in them, protected from surface radiation and other destructive elements.

“There is probably nothing living there now,” Day told Lester. “But if there ever was anything on Mars, this is a better place on average to look.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook