Sentiment Albums Hold the Seeds of Modern Fandom

These socially connected, multimedia 18th-century assemblages were more than the sum of their parts.

To be a fan is to be a perpetual collector, and that doesn’t just mean autographs or action figures. Acquisition is an important part of many fans’ lives, from the material, such as concert merch or rare comic cover variants, to the intangible—facts, memories, interpretations, arguments, ideas. They save images, curated and annotated lists of fanfiction, data about fictional universes for wikis, clips from their favorite shows for vids. They deconstruct their obsessions, and build something new from all the little pieces. Sometimes they do this alone, but often, they do it together—the shared act of creation often defines a fandom.

Modern fandom online is a vast and varied place, and some of its practices are shaped by the platforms where fan communities gather. On TikTok, fans might make videos they hope will reach millions of eyes, while closed spaces such as Discord might only reach a dozen intensely interested people. Tumblr is still home to a great deal of fan activity despite the turmoil of the past few years. There, people spin up blogs for specific obsessions—the stuff they love, or love to hate, or simply spend way too much time thinking about.

I joined Tumblr more than a decade ago, and when I fell for a new show (BBC’s Sherlock—sorry, I know), I began to participate in fandom there. That meant reblogging gifs and fanart, and writing and responding to others’ analysis—what fans call “meta”—which others would then post to their own blogs. The accumulated grid of various kinds of content was a visual representation of the obsessive churn of my brain—I was building a record of my fascination, piece by piece.

Then I think back further, a decade and a half before, to one of the friends with whom I shared a love of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. She kept a large three-ring binder full of images related to the show that she’d clipped from magazines; I decided to copy her, selecting cut-outs from Seventeen and TV Guide and Fangoria to carefully paste into a binder of my own. It was a proto-Tumblr, full of my analog reblogs. I’d flip through the binder from time to time, admiring the accumulation of another record of fascination.

What I was doing in the binder and on Tumblr, what millions today do across the internet in all these various forms, is a practice with deep roots. The desire to collect, compile, and share the things you love stretches back centuries. If there is a seed of modern, connected fandom, it might be in what was once called a “sentiment album.”

For centuries, the creation of a “commonplace book” was a core practice for many in Europe who could read or write. These were places to record information you might not have physical access to again—more a note-taking app than a journal—as well as a way to order your thoughts. “The idea of a commonplace book grew out of the Renaissance, and it was important when people didn’t have access to large personal libraries—when books were really expensive,” says Evan Hayles Gledhill, a gothic specialist who teaches queer cultures and gothic literature at the University of Warwick and Bath Spa University.

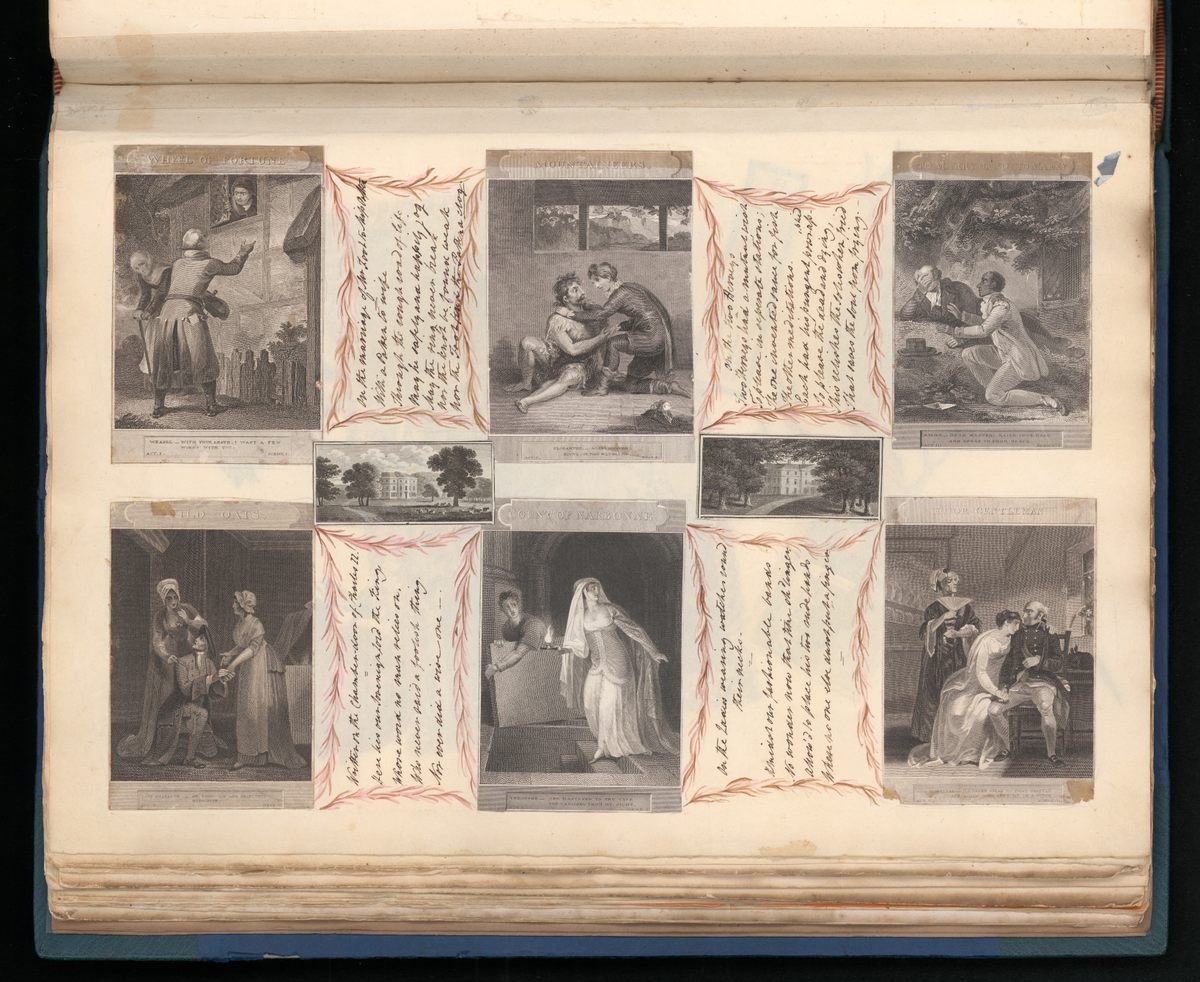

Commonplacing was famously documented by John Locke, one of many Enlightenment thinkers who advocated for its universality as an intellectual exercise—though unsurprisingly, while the practice could cross class lines, it largely remained the province of men. But in the 18th century and into the 19th, a related practice emerged primarily among women, many of them teenagers: “sentiment albums.” Like commonplace books, these albums were places to record meaningful quotations and copy poems (alongside paintings, sketches, and other visual elements). But they were not meant for solitary reflection; they were networked texts, publicly displayed and shared among friends, who might leave autographs or more substantial contributions in the books of their peers. And they were, per their name, affective spaces—catalogs of things their authors found emotionally resonant, not just academically important.

“The phrase ‘sentiment album’ tends to get used to separate out from a commonplace book, which might have a more practical use, in terms of your scholarship being necessary to you,” says Gledhill. “Whereas the sentiment album is very much, in the broader sense of the word, ‘sentiment,’ about feelings. It’s about things that appeal to you, it’s about things that you like. It’s about copying out your favorite quotes from your favorite authors, keeping things close to you.” The contrast between the two practices illustrates a particular sort of irony in the “universality” of commonplacing. “We’ve got this interesting dichotomy between, ‘Commonplacing is for everyone, it’s an intellectual tradition, it is philosophically objective,’” explains Gledhill. “But on the other hand, these guys would absolutely throw a fit if you suggested teenage girls could be equally as good as they were at doing it.”

Many surviving sentiment albums show that their teenage girl creators were certainly as good as any commonplacer (or Tumblr user, for that matter)—intricate, gorgeously constructed books, privately made but publicly shared. Commonplace books, in contrast, were rarely socially circulated. “You might ask someone to send a passage from their library—which you would paste into your commonplace book—if they had a book that you didn’t have,” Gledhill says. “The sentiment album was very much about forging networking and friendships. When you went to visit people, you would take it with you, and get people to circulate things for you, and copy in their favorite poem.”

As so often happens with women’s—and especially young women’s—practices, contemporary commentators didn’t think particularly highly of sentiment albums or their authors. Many objections focused on the transformative juxtaposition of original writing with famous quotations and poems, described by one anonymous commentator in 1825 as “verses on stilts, and prose run mad—elegant extracts without elegance, apothegms without instruction, epigrams without point, and repartees without meaning.” Aside from suggesting women didn’t understand the words they were mashing together, publications at the time complained that album creators were too motivated by feeling, and too interested in the social component of the practice. Commonplacing was an important part of solitary scholarship, but sentiment albums were about speaking to (and performing for) your friends, they posited (as if that was a bad thing).

Both sentiment albums and commonplace books were eventually packaged and sold in more prescriptive ways: Rather than a blank book, you might buy an “annual” with selected (and, importantly, “appropriate”) poems alongside space for you to add your own content. Eventually that prescriptiveness came to dominate the form. Later in the 19th century, sentiment albums gave way to more rigidly formatted scrapbooks and photo albums, just as commonplace books were replaced by collected volumes of quotations and aphorisms.

But it’s easy to see echoes of the sentiment album in modern fandom—especially in a place like Tumblr. In their writing about the practice, Gledhill goes beyond the aesthetic similarities. Album creators, like Tumblr users, used recompositions to make arguments about specific objects of affection, or recast them in new contexts, they say. It’s clear in the social networking parallels, as well, as books were passed around and collectively added to, like a meme that transforms as it spreads across platforms, and it’s clear in the affective parallels. Is crushing on a Romantic poet any different than a TikTok fan edit of your favorite singer? Is writing a poem in your friend’s album not similar to building on your friend’s headcanon in the comments? It’s all lovingly chosen, carefully stitched together, a whole bigger than the sum of its parts.

Elizabeth Minkel has written about fans and fandom for WIRED, The Guardian, The New Yorker, New Statesman, and many other publications. She’s cohost of the Fansplaining podcast and co-curates the Hugo-finalist newsletter “The Rec Center.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook