The Itinerant Princess Who Chronicled Akbar’s Mughal Empire

The daughter, sister, and aunt of emperors, Gulbadan Begum wrote of a Mughal Empire few witnessed.

Excerpted and adapted with permission from Vagabond Princess: The Great Adventures of Gulbadan by Ruby Lal, published February 27, 2024 by Yale University Press. All rights reserved.

On the banks of the River Ravi in the prosperous agrarian province of Punjab, India, the city of Lahore was earning a reputation as a grand Mughal city. In late 1585, the Mughal Emperor Akbar moved his government there. For over a decade, the fort of Lahore had been getting a facelift, rebuilt handsomely in kiln-burnt brick and stone, its 11th-century mud-brick foundations barely visible.

In the interior of the solid Mughal fort was the stately harem where Mughal princess and poet Gulbadan Begum had relocated after a 3,000-mile-long pilgrimage to Mecca. A shortage of water, which was in any case of poor quality in Fatehpur-Sikri, the former Mughal capital, was a catalyst for the royals to move. Lahore also was a strategic location for Akbar to keep track of his territories to the northwest; if required, he could take swift military action. Splendid guesthouses, awe-inspiring pilgrimage centers, bustling bazaars, delightful gardens, and a potpourri of languages and cultures added to Lahore’s appeal.

Gulbadan was not in pursuit of legendary gardens, shrines, or mosques—curiosity, she knew, began within. Five years after her return from Mecca, she began another astonishing journey, this time from behind the parapets of the harem in Lahore. A new vision within the ramparts, her venture was linked once with her nephew Akbar’s ambitions.

Around 1587, Akbar made an announcement that would transform the idea of record keeping in Mughal history. His latest declaration was in line with his determination to be remembered as an unprecedented monarch. The emperor could not read or write; he was an ummi, an inspired mystic, or someone whose knowledge came directly from divinity, not schooling. Each evening, select reciters read books aloud to Akbar. Over twenty-four thousand books and manuscripts were in the imperial library and the harem precincts.

The kitabdar, or head librarian, his assistants, and staff cataloged, numbered, and classified works, entering their details into separate registers for each subject, including astronomy, music, astrology, mythology, books of advice, and commentaries on the Quran. Scribes, calligraphers, and bookbinders busily worked in the library and ateliers, encasing manuscripts in silk, binding them with lacquer or leather, and engraving and inscribing them.

This book-loving, greatly ambitious Emperor Akbar arrived at a historic decision. It was time to compile a monumental history of his empire so that posterity would never forget his grandeur or his dynasty. Akbarnama, or “the History of Akbar,” was to be the official history of the Mughal Empire, unrivaled in scope. Abul Fazl, the emperor’s chosen chronicler and devotee, felt that such a history had to start at the very beginning. Even though it was to be all about the emperor and the splendid empire he created, ancestors were imperative to the story, as grand roots gave legitimacy to power.

And so in 1587, Akbar sent out orders to several “servants of the state” and “older members of the Mughal family” to write their impressions of earlier times, which would be used for Abul FazI’s official history. Among the officers and servants, the emperor selected Bayazid Bayat, who oversaw the imperial kitchen, and Jawhar, the former water carrier of Humayun.

Akbar also approached one venerable woman: his accomplished Aunt Gulbadan, now 63, the astute witness of events of the Mughal dynasty who had recently returned from her own glorious adventures in the Arabian peninsula. The emperor considered her the best person he could turn to for accurate and detailed information about his dynasty.

“An order is handed out.” Gulbadan wrote in the first line of her book. Hukm, imperial command, the Persian word she used, was suggestive of the urgency and importance of the royal project. She spelled out the directive: “Write down whatever you know of the doings of Firdaus-makani and Jannat-ashyani,” and featured the posthumous descriptions of Mughal Emperors Babur and Humayun: dwelling in paradise, nestling in paradise.

Akbar’s selection of his aunt for his new project to record the history of the empire speaks of his admiration for her as a dynastic memory keeper—his salute to her unique experiences. He could have asked Hamida, his proficient mother, an ardent book collector and patron of some of the finest visual works of the Mughal atelier. She was more involved in the day-to-day events of his rule. In any case, he knew that his mother and aunt were intimate.

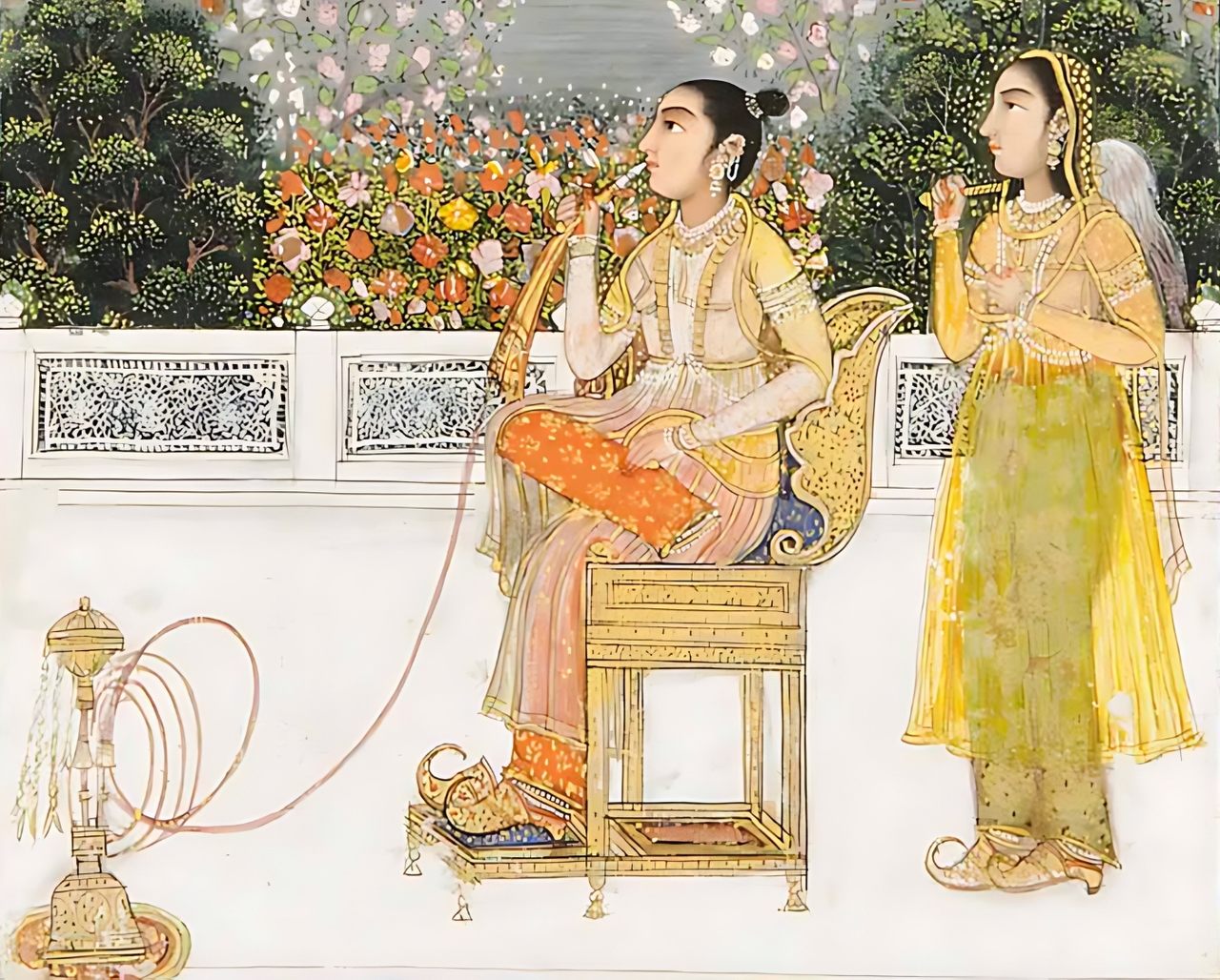

Without doubt, the two would work together in reconstructing the Mughal past. During royal hunting expeditions, the tents of these two women were always next to Akbar’s, signifying their elevated status. In a delightful painting of Hamida’s wedding celebrations that she herself commissioned, Princess Gulbadan sits across from Hamida and Humayun. Joined at the hip through time and space, the two worked in concert in the new imperial endeavor, carefully documenting the polychromatic women’s world in movement.

The men invited to contribute to the new imperial history busied themselves with famed books and tracts by men, met with religious and court authorities to compile the feats of kings, and wrote their own odes to Mughal wars and victories. Meanwhile, Gulbadan began to gather information in storytelling sessions. Stories: that is how royal women spoke and shared the stuff of human history, stories within stories that may have been told over a thousand and one nights or more. The harem in Lahore bustled with women recalling and sharing tales. The princess’s vision, which had unfolded in the peripatetic life that she and her circle embodied, would now be recorded in the pages of her book.

Nearly 60, dressed in a classic long kurta and salwar narrowing at her ankles, her head concealed in a dupatta dotted with sparkling silver sequins, Hamida enlivened the female deliberations. Gulbadan adds the phrase “Hamida Banu says” to her sentences. Queen Salipan, Gulbadan’s companion in adventures across the seas, was part of the assembly. Perhaps she jogged Gulbadan’s memory or fine-tuned her recollections. Queen Harkha, mother of Prince Salim, Akbar’s third son, may also have joined them. Fairly stooped by this time but still sprightly, Bibi Fatima was there. It is certain that the women held many assemblies. Attendants brought food and wine. Together, they looked at prized books and paintings housed in the harem and shared their stories.

Gulbadan’s nieces would add their points of view. The elderly Gulnar would simply be amazed at how far the Mughal household had come since the days of their arrival in Agra.

Women attendants, companions, and caretakers gathered below a red awning in front of Gulbadan’s quarters. Hamida sat beside Gulbadan, the princess relaxed as she looked at the women. Gulbadan typically dressed in a long top, as in Mughal miniatures, as well as embroidered trousers and a dupatta thrown over her shoulders. Her luminous eyes, a striking feature, were agile and attentive to detail.

Her book originated from shared stories, which she wrote in conversational Persian laced with words in Turki, her mother tongue, and Hindavi.

This was an accessible book from a master storyteller who weaved stories within stories and created dramatic pauses in her prose by shifting the narrative from one time to another. Events do not always appear chronologically in Gulbadan’s book, for she would reflect on older times as she wrote about new ones.

Gulbadan offered a unique chronicle suffused with feeling. We saw in the pages of this book that although she did not describe her husband, son, or daughter, she keenly documented childbirth, children killed in war, unfulfilled desires, anticipation in love and marriage, and the simultaneity of war and peace. Individualism does not inform her narration, although she brings individuality to each person. Her recollections of joy, sorrow, matrimony, motherhood, and sovereignty illustrate a collective, universal experience.

Thanks to her recognition of the fragility of human beings, we meet in her book human kings, uncertain leaders, and emotional, demanding women who raise with Babur and Humayun the thorny subject of the lack of time spent together. Heart-wrenching discussions; the pain of infertility; the bold questions that Hamida posed to Humayun before she agreed to marry him; royal women’s abductions; special pleading by matriarchs on behalf of their sons; women dressed as men; anguish, laughter, and tears are all part of her narrative. Odd places, ordinary people, kind and evil servants, gentle eunuchs, resourceful women, and playful children—and the lives of people who do not normally appear in the annals of the Mughal Empire—all take center stage in Gulbadan’s history.

Her writing was distinct from anything that official chroniclers or servants produced. Invited male contributors favored tarikh, a historical, chronological narrative; takireh, a linear biographical or autobiographical mode; qanun, a normative account or legal text; vagi’at, the narration of happenings, events, and occurrences; or nama, a genre that includes histories, epistles, or accounts of exemplary deeds. All of these were firm assertions of male thinking.

The power of Gulbadan’s book is that it is a constellation, not a categorizing of episodes. Patterns of peripatetic Mughal times emerge in her assembling, but not through an instructive mode. She called her book Ahval-i Humayun Badshah, or “Conditions in the Age of Humayun Badshah.”

Conditions, states, and circumstances—an open-endedness animates the word ahval, perfectly befitting the Mughal era in which men and women were frequently on the move while celebrating births, mourning setbacks and losses, and learning new philosophies of artful living.

In the first portion of her two-part book, Gulbadan explores her father’s, the Emperor Babur’s, daily life. We see the dynamic facets of his wanderings in Afghanistan and Hindustan, his desperation and longing during wars and victories, and the messy early years of Mughal rule in Hindustan. We also find rare, nuanced, and complex accounts of Mughal home life—especially in comparison to how those issues are discussed in other chronicles. We meet the young Gulbadan in Kabul, amazed at the curiosities of Hind, a southeastern Sasanian province near the Indus River, traversing the Khyber Pass to begin a new life in Agra in the aftermath of her father’s victories. This is the only fully autobiographical part of her writing.

In the second part, she devotes substantial space to her favored half-brother Humayun’s exile and kingship. We glean fabulous details of his desert wedding to Hamida and her legendary prenuptial negotiation. We learn about Mughal women lost in wars, the debacle in Chausa where the Afghan leader Sher Shah Suri defeated Humayun in 1539, Akbar’s birth in the harsh circumstances of his parents’ itinerant life, and senior women’s feasts at Humayun’s accession and Hindal’s, Babur’s youngest son’s, wedding. The lost world of the court in camp is animated in a way that no other chronicler of the time even approaches.

![Anne Bonny and Mary Read were both "convicted of piracy at a Court of Vice Admiralty [and] held at St. Jago de la Vega on the Island of Jamaica, 28th November 1720," according to the inscription accompanying this 1724 Benjamin Cole engraving from <em>A General History of the Pyrates</em>, by Daniel Defoe and Charles Johnson.](https://img.atlasobscura.com/5_kDHgENxQkc0QzZuPs_kICvmEP5JNCV8bcXDI7m5Do/rs:fill:600:400:1/g:ce/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy81NDQ0ZGNiMi1m/YzRkLTQ4YjUtYTVh/MC0xYzU2ZDliOTY0/YjY1NGNkMWI4MWEw/OTExMDM5ZTZfQW5u/ZSBCb25ueSBhbmQg/TWFyeSBSZWFkIC0g/RmVtYWxlIFBpcmF0/ZXMgaW4gMTgwMHMu/anBn.jpg)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook