One Man’s Fight to Preserve Pakistan’s Perfect Cooking Pot

The gorkon is a marvel of heat retention that’s at risk of disappearing.

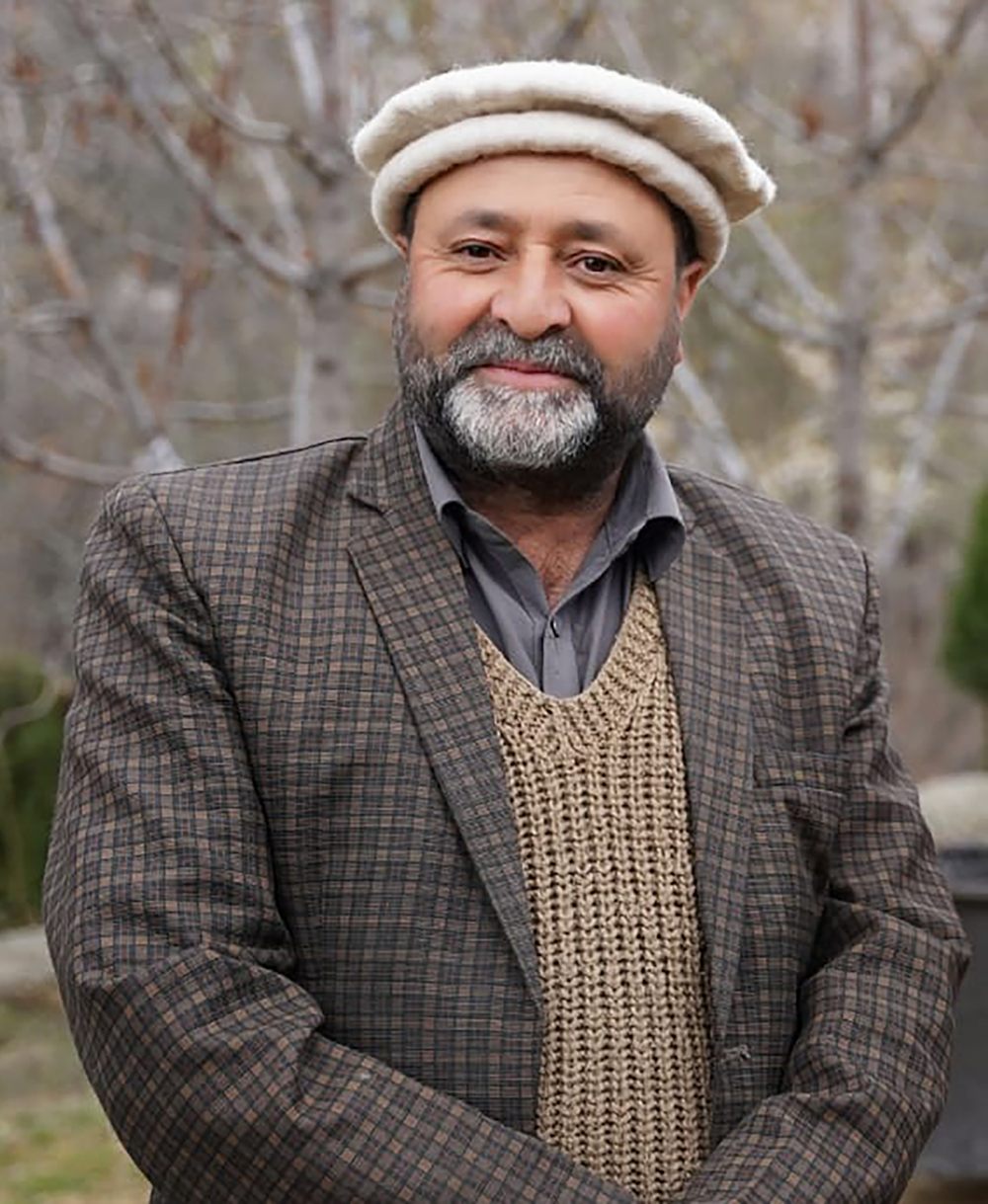

In 2000, a Japanese tourist walked into Syed Israr Hussain’s guest house in Minapin, Pakistan. While most visitors come to the village, nestled in the Nagar Valley below Rakaposhi mountain in the Karakoram range, to hike or summit the peak, this tourist had a different agenda.

The tourist asked—no, “he demanded,” remembers Hussain—to be served a very specific meal. He had fond memories of a delicious chicken stew he had eaten when he visited the village 30 years earlier. The stew, he noted, had been cooked to perfection in a gorkon, a lidded pot carved from local stone. Hussain was taken by surprise by the request. Although he had memories of his grandmother cooking meat and turnips in a gorkon during winters when he was a small child, it had been a long time since he had seen one being used—long enough that he had almost entirely forgotten about them.

Undaunted and curious, Hussain began looking for gorkon pots within Minapin. He found a local who had a long-since used one and let him try it. Hussain brought the gorkon to the guest house, soaked it in water to restore it and clean it of decades-old dust, and made chicken stew for the guest. The stew was exactly what the tourist remembered. Hussain says this episode led him to bring back this old tradition by introducing the cooking method in his restaurant.

The gorkon is a bit of a marvel. Once removed from a heat source, it will keep the stew inside boiling for over half an hour, depending on the size of the pot, and warm for much longer. Traditionally, the gorkon was carved from a stone known in the local language as balosh, though other types were also used. Before modern iron tools, artisans used the hard horns of the local Himalayan ibex to carve the stone into pots. This process took two to three years for one single gorkon, making them prized possessions passed down from generation to generation.

But over the past several decades, the treasured vessel has disappeared, a victim of a changing culinary landscape in Gilgit-Baltistan, the region where Minapin is located. The completion of the Karakoram Highway in 1978 ushered in a cooking revolution in the area, and once-common foodways were replaced by new ones. For one, pressure cookers arrived, bringing with them an ease and speed of cooking that the gorkon couldn’t match. The gorkon, which means “sizzling pot,” had been a staple of the kitchen in this area for hundreds of years, if not more (no one knows its exact origin). But with the arrival of the pressure cooker, steel, and other modern cooking methods to this once-isolated place, gorkon cooking began to fade away.

And it wasn’t just the cooking methods that changed; what locals cooked changed, too. Whereas food once revolved around simple, local ingredients like apricots and their oil, walnut oil, and homemade butter (known as desi ghee), today you can find a variety of foods that are more heavily spiced and that migrated from elsewhere in Pakistan.

Osho Thang, Hussain’s guest house, has become a hub for restoring some of these lost traditions. For the past few years, Hussain has collected old pots from Minapin and the surrounding villages in the Nagar Valley and cooked in them for his guests. Today, he has a large collection of gorkons, some almost 200 hundred years old. The pot, Hussain explains, has become his trademark. The food his restaurant cooks in the gorkons is very traditional: “No masalas, because in the old times there were no masalas here, only simple things,” he says.

But simple does not mean bland. The food cooked in these pots—typically chicken or mutton stew with onions, tomatoes, and some spices—has a distinctive taste that cannot be achieved by other cooking methods, according to locals. The slow cooking renders the meat so tender you don’t need a knife, and the gorkon itself imparts the sort of earthy flavor that stainless steel can only dream about. The spices are mild and let the fresh flavors of Hussain’s free-range animals and organic ingredients shine. And outsiders agree: Hussain’s gorkon food attracts tourists, both local and foreign, and Osho Thang has become a culinary destination.

“It is our culture, you know, and it is tasty,” Hussain says. “Back in the big cities in Pakistan they have modern pots,” but in Minapin, they have the gorkon. “They like to eat pizza,” he says of city-dwellers with Westernized diets. “But this is not our culture.”

Others in Gilgit-Baltistan have taken notice of Hussain’s work. When he began to experience success with gorkon-made meals by attracting attention and guests to his restaurant, other guest houses and restaurants started offering them, too. Some of these places are located in the same village as Hussain, but others are in different parts of Gilgit-Baltistan.

Some notable visitors to Osho Thang seeking gorkon food, according to Hussain, have included the prime minister of Pakistan and the U.S. ambassador. The allure of the gorkon draws people into a region that is difficult to access, bringing with them much needed tourist money and the promise of a new audience for old traditions. Some tourists even want to buy a gorkon and take it home, and to accommodate that demand, a few local shops now sell gorkons, both old and new.

Unfortunately, buying new gorkons may soon become impossible. With lower demand for the pots in the post–Karakoram Highway age, combined with other cultural changes, fewer artisans are learning the craft of producing the vessels. Hussain, who has become a respected authority on gorkons, says that, to his knowledge, there are only two artisans still carving gorkons in all of Gilgit-Baltistan.

But even if only old gorkons remain, Hussain’s quest revived a tradition on the brink of extinction, and in the process brought attention to Gilgit-Baltistan’s culture and foodways. Local families, too, have taken up gorkon cooking once more, keeping the tradition alive. Hussain, for one, is grateful for what the gorkon has done for the region and himself: “I’m thankful to this pot.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook