In Mesopotamia, Being ‘King for a Day’ Could be Deadly

Total solar eclipses were an omen of death for rulers of the Assyrian Empire. The fix? Install a fake king and then kill him.

The eclipse is coming. Preparations are underway, and everyone is buzzing with anticipation. You are getting anxious.

It is early June, in the year later known as 763 B.C. You are a prisoner of war in Nineveh, the capital of the Assyrian Empire, and you have good reason to be afraid.

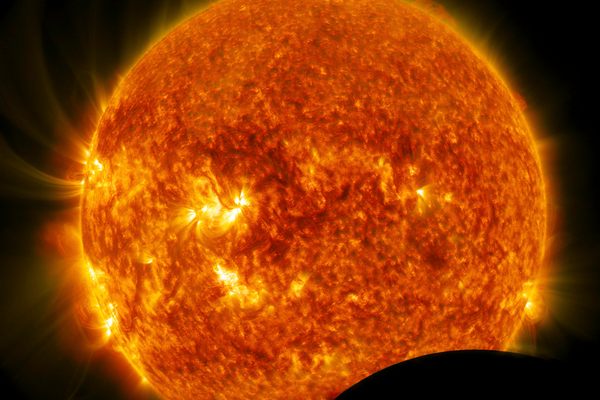

The Assyrians worship the Sun God, the Moon God, and other sky deities, so a total eclipse of the Sun—even though you are not quite sure what, exactly, will happen during such an event—holds tremendous spiritual and political significance. The empire’s sky priests were skilled diviners of nature, studying the motions of the Moon, the planets, and the stars from their temple academies to read omens from the gods. They knew a total eclipse could be very bad news: If it was forecast to fall over Assyria, like the one in June 763 B.C., the eclipse would foretell the death of the king.

And this is why you are afraid: You’ve heard the rumors, and don’t want to be chosen as his substitute.

Across cultural groups and political dynasties on every continent, eclipses of the Sun and Moon have long been profound spiritual and cultural events. The banishment of the Sun behind the Moon in particular has represented many things, from a demonic dragon devouring the Sun in both Inca and Chinese lore, to the death of the sun in Navajo Dine cosmology. In northern Mesopotamia, by the 10th century B.C. at the height of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, the priests knew that if the planet Jupiter was visible as the eclipse passed overhead, the king was doomed. The empire’s scholars could predict eclipses, and priests used that information to enact safeguards that could mitigate the bad omen—or at least transfer its curse to someone else.

The most important such ritual was called šar pūḫi in Akkadian, the “substitute king ritual.” It is one of the most elaborate yet lesser-known human sacrifices of antiquity. If priests divined an ill omen in a forthcoming eclipse, the real king would go into hiding, while a substitute was placed in his stead for anywhere from a few days to three months. The substitute king would enjoy all the trappings of regency before being ritualistically killed to fulfill the prophecy. He would be wined and dined, presented with gifts, and, according to some accounts, even provided with a virginal queen as his consort. Meanwhile, the real king would continue conducting palace business somewhere safely out of sight. On the appropriate day, decided by royal diviners and astrologers, the doppelgänger was sacrificed. Sometimes the person was given a poisonous drink; sometimes he met his end by more violent means. But only after the substitute king was killed could the real king resume his duties publicly.

Though they probably reached their height during the Neo-Assyrian Empire, substitute king rituals outlasted that empire’s rulers and continued into the second century B.C. The last records of the substitute king tradition dates to 194 B.C., long after the fall of Babylon to the Persian Empire.

The ritual may date to the deepest roots of the Assyrian Empire. There is a potential reference to it as early as 1500 B.C., in the Old Babylonian period, when scribes first compiled the astronomical compendium known as Enuma Anu Enlil. The document is something like a Babylonian-Assyrian star chart augmented with thousands of omens that specify events that will occur based on celestial alignments. For instance, one tablet warns that if an eclipse in the springtime month of Nisannu coincides with a certain planetary alignment, “the king of Akkad will die.”

The records in Enuma Anu Enlil and other ancient Mesopotamian texts were used to divine bad omens and prepare for them. What their record-keepers probably did not intend, but what happened anyway, was the beginning of scientific record-keeping. The careful records of Mesopotamian sky priests enabled the first exact science in antiquity: the science of astronomy.

Over time, the rituals designed to prevent the death of the king got increasingly complicated. By the eighth century B.C., a substitute king would have had his own court, including cooks and entertainers. Only a few members of the real king’s inner circle would know about this; most of the public wouldn’t know what the real monarch looked like anyway, so he could continue working while his substitute lived the (time-limited) high life.

People may have volunteered as tribute, so to speak, but more often the sacrificial rex would be a prisoner of war, criminal, or peasant—someone who wouldn’t be missed by the general populace.

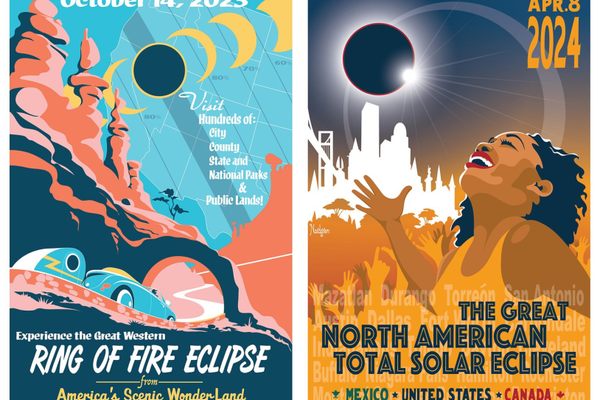

Nearly 3,000 years after prisoners of war and other unfortunate souls dreaded being named the chosen one, be grateful that the only risk you face for the April 8 total solar eclipse is a potential sunburn (because we know you’ll definitely be wearing your protective solar eclipse glasses, right?). It could be much worse.

Wondersky columnist Rebecca Boyle is the author of Our Moon: How Earth’s Celestial Companion Transformed the Planet, Guided Evolution, and Made Us Who We Are (January 2024, Random House). She is a featured speaker at Atlas Obscura’s Ecliptic Festival, April 5-8, 2024, in Hot Springs, Ark.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook