The Tale of the Mad Stone, the One-Time ‘Cure’ for Rabies

Before vaccines, pseudoscientific folks remedies for the deadly virus involved mysterious animal-vegetable-mineral hybrids.

One August morning in 1923, a farmer in Missouri named Adam Rarely heard his pigs squealing and went out to investigate. He found a strange dog in the pen. As Rarely attempted to defend his livestock, the dog attacked and bit him on the leg before he could manage to kill it. Neighbors came and quickly concluded that the dog was rabid, which meant Rarely was in serious trouble. He quickly got on his horse and rode 25 miles to the town of Buffalo to see the Reverend William Newton Sutton. Sutton, Rarely believed, was his only hope for survival.

Sutton welcomed him in, had him sit down with his leg elevated, and sent his youngest son to fetch some fresh milk. The reverend then went upstairs to retrieve his prized possession: a small, grayish-white stone. It had been in his family’s possession for decades, since some time after the Civil War—an ancestor had acquired it from a German immigrant who’d settled in Arkansas. This stone, a mad stone, they believed, had the power to cure rabies.

Sutton had treated more than a thousand people with his mad stone, never charging anyone, as the objects were sometimes said to lose their efficacy if they were involved in monetary transactions. The curative power of this rock was widely known; multiple doctors had tried to buy it from Sutton, who’d vowed never to sell it.

Sutton soaked the stone in the fresh milk and then placed it gently against Rarely’s wound for four or five minutes. As Sutton removed his hand, the stone stuck. This, as far as Sutton and Rarely were concerned, was proof positive that the farmer had been infected with rabies. So they waited.

After six hours, the stone fell away on its own. Sutton washed it, and then put it in a pot on the stove that he filled with milk. As he warmed the milk, a green scum formed on the surface, which, Sutton explained to Rarely, was the poison. Then the reverend placed the stone back on the wound, and this time it stuck for two hours. The process was repeated a third time: 45 minutes. On the fourth try, the stone would not stick at all—Rarely was healed.

I first read about Rarely’s story in an article on mad stones by folklorist and musician Loman Cansler, who claims to have heard it firsthand from Sutton, and I’ve kept it in my files for some time now—a story that, even as I have the means to explain what happened, unsettles me in ways I can’t quite explain. There is the strangeness of the ritual—the milk, the green scum, the waiting. There is the terror of the alternative, the slow, inevitable, painful death by rabies. But mostly there is this strange and anomalous object at the center of it, inert but somehow radiating power.

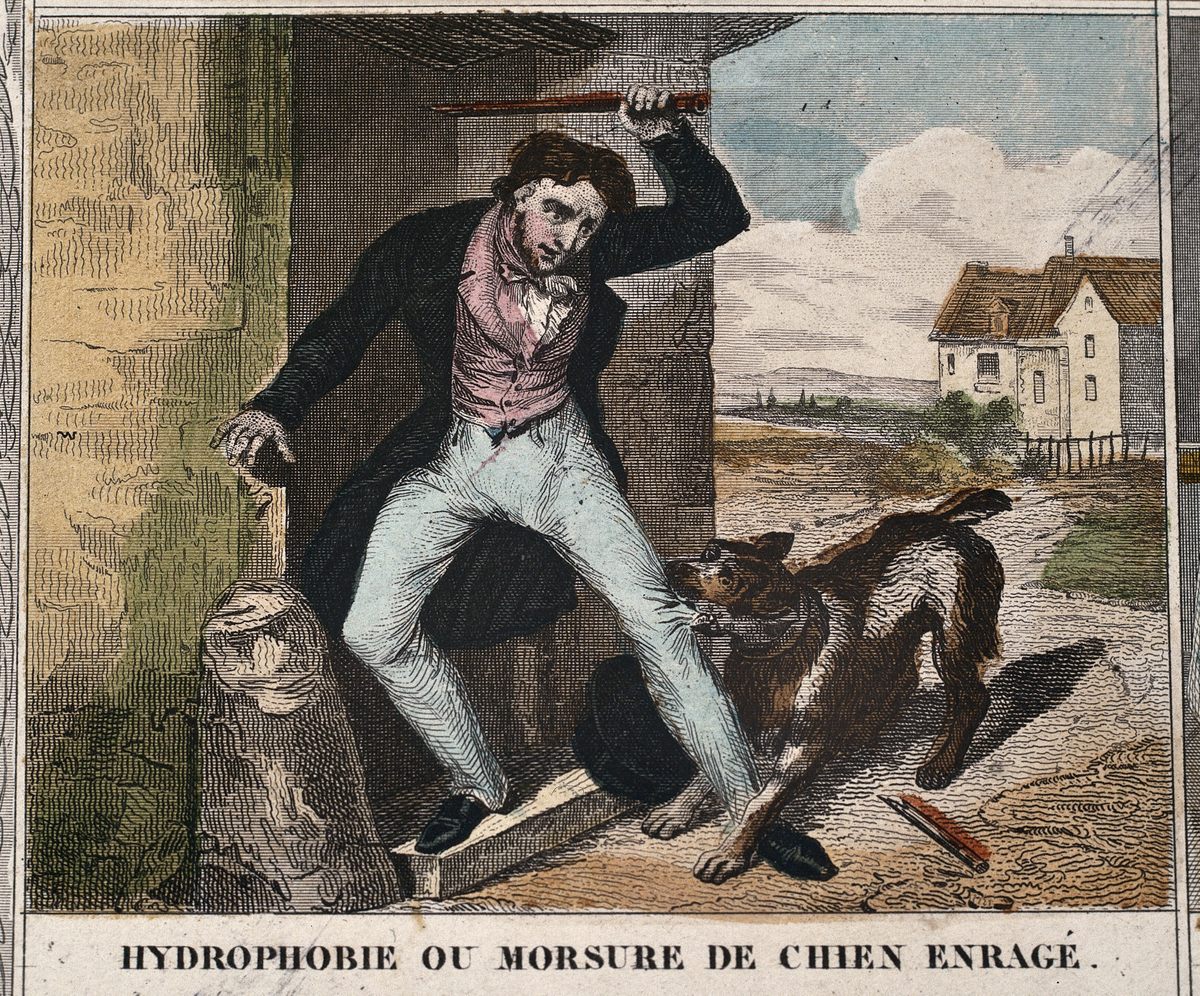

For centuries, rabies was one of the great scourges of humanity. A disease that famed 11th-century Muslim physician and philosopher Ibn Sina (commonly known in the West as Avicenna) once referred to as that “serious and venomous melancholy,” it attacks the central nervous system, from the point of contact on a one-way path to the brain. Believed to be particularly prevalent in late summer, particularly in the so-called Dog Days (July 24–August 24), when the dog star Sirius rises in the sky around the same time as sunrise, it terrified because it was highly visible and inevitably fatal, if somewhat rare. (Between 1840 and 1906, New York City recorded no more than seven cases of rabies a year, as opposed to thousands of deaths annually from tuberculosis.)

While rabies can be spread by numerous wild animals—from bats to raccoons—it’s long been associated with dogs. As Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy write in their study of the disease, Rabid: A Cultural History of the World’s Most Diabolical Virus, “Rabies coevolved to live in the dog, and the dog coevolved to live with us.” The appearance of rabies is an uncomfortable reminder of this proximity, this recognition that the worlds of the human and dog are coterminous. Beyond that, there’s something far more terrifying about the sickness itself; the person exhibiting symptoms of rabies has, in some sense become canine: increasingly feral—less human—as the disease takes its awful toll. “The rabid bite,” Wasik and Murphy write, “is the visible symbol of the animal infecting the human, of an illness in a creature metamorphosing demonstrably into that same illness in a person.” Rabies reminds us all how perilously thin the barrier between human and animal really is.

Prior to Louis Pasteur’s invention of a vaccine in 1884, there were precious few treatments for rabies, preventive or otherwise. One was cauterization—known as St. Hubert’s Key (after the patron saint of hunters). Usually a piece of iron in the shape of a nail or a cross, it was heated white hot and pressed against the wound. While it seems barbaric and superstitious, at least in theory it could work if carried out quickly enough after an infected bite, since it has a chance of killing the virus at the site of the infection before it begins traveling up the nervous system. In some cultures, when someone would finally begin exhibiting symptoms of the disease—such as hydrophobia, a severe aversion to water, which is often how the disease is termed in older sources—relatives would come together and throw a heavy blanket over them and smother them, not only to hasten the death but also so no one person had to feel responsibility for the killing.

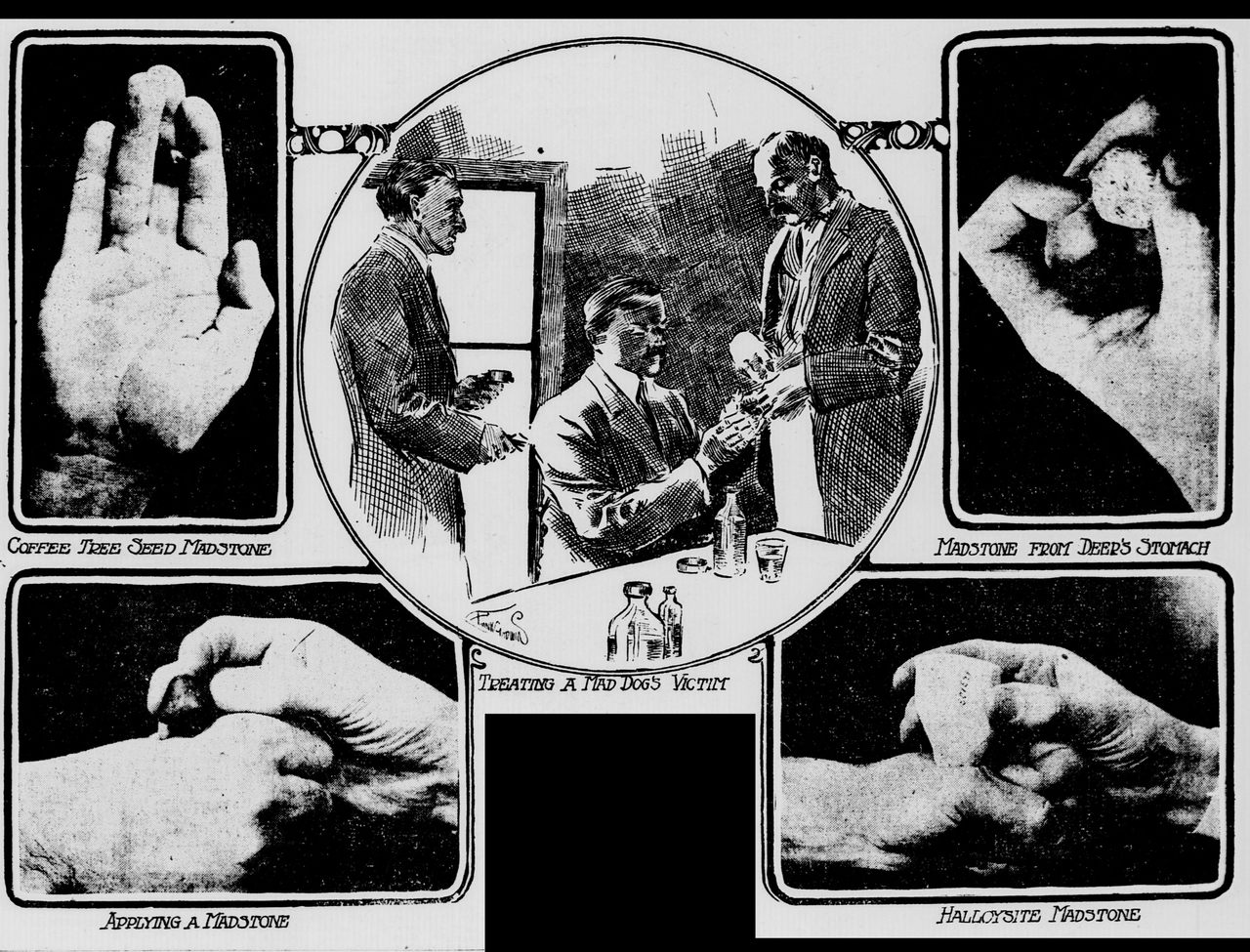

The other widely used remedy was the mad stone, used largely the way it is described in Adam Rarely’s story: fresh milk, adherence to the wound, boiled in milk to remove the poison, reapplied until it would no longer stick. (A variation on this treatment, in which fur from the rabid animal itself was pressed against the wound, ultimately gave us the expression “the hair of the dog that bit you.”) It could only be used on humans and was temperamental in the way that magical things are. In addition to concern about charging for its use, if a mad stone was applied to animals, it would lose its power to heal people. Importantly, the patient had go to the stone—it could never be brought to the patient. There’s no definitive account of mad stones or how they were used, just newspaper articles, guides of folk remedies, and legend.

Perhaps the most famous person to seek out this cure was Abraham Lincoln. In 1852, Lincoln traveled with his son Robert from Springfield, Illinois, to Terre Haute, Indiana, after Robert had been bitten by a dog. As Edgar Lee Masters recorded in his 1931 biography Lincoln the Man, “He believed in the madstone, and one of his sisters-in-law related that Lincoln took one of his boys to Terre Haute, Indiana, to have the stone applied to a wound inflicted by a dog on the boy.” In 1936, historian Max Ehrmann attempted to verify this story, and found numerous secondhand witnesses who testified that Lincoln had indeed made the trip for this purpose, though he could not verify whose mad stone it had been.

Describing what a mad stone is supposed to do is easy; describing what it is turns out to be much harder. They came in any number of shapes and sizes: black, brown, gray, shades in between. They ranged in size from a several inches to not much larger than a pumpkin seed. Different thicknesses and widths, innumerable shapes—the only defining feature the stories share is their ability to cure this specific, deadly, viral infection.

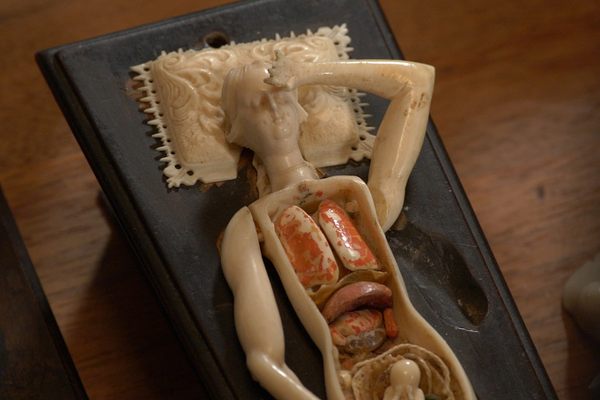

Most of the stories agree that mad stones were not geological in origin, but came from animals. Some say the stomach, some the head or neck or heart or shoulder. Some claim they were found in moose, others elk or buffalo, or deer—particularly white deer or otherwise rare ruminants. The New York Times gave a largely credulous account of them in May 3, 1885, stating that mad stones were said “to be formations found in the bladders of deer and only exist in those animals that live in a high, dry climate where there is not a full supply of water and the water drank is impregnated with limestone.” In general, people believed that mad stones form when a deer or other ruminant swallows a foreign substance that gradually become coated in the stomach with layers of hair, along with magnesia or phosphate of ammonia. As one source explained, the mad stone was “a compact of Vegetable and Mucus Matters, and formed by a freak of nature in the small or second stomach of a Hermaphrodite Deer, and so constructed with its innumerable cells that when applied to the lacerated flesh, it adheres at once and every cell exercises a suction power, but does not absorb any substance except Virus; because the cells are too diminutive in size to take in even blood, which is too coarse and tough to gain entrance.”

The mad stone, in other words, is a variation on the bezoar: a real phenomenon that occurs in ruminants whereby a mass of swallowed matter is compacted into a small, hard orb that is passed through the animal’s digestive tract. The word “bezoar” comes from the Persian for “antidote,” and such objects were long believed to have medicinal properties. In fact, modern chemical analyses have shown that certain bezoars, when immersed in a solution that includes arsenic, can indeed extract the poison from the liquid.

Many mad stones, it turns out, were not formed this way at all. One, owned by a J. M. Dickson of Kansas City, was found to be fossilized coral; another, presented to the doctor W. J. Hoffman in North Carolina turned out to be just an interesting-looking pebble. In 1976 Yale School of Medicine faculty Thomas R. Forbes gathered up a number of reports of mad stones and found them to be, variously, aluminous shale, white feldspar, halloysite, and other minerals. One, offered to the Smithsonian as a genuine mad stone for the low price of $1,000, turned out to be the polished seed of a Kentucky coffee tree. While some indeed could have been bezoars of various kinds, what seemed to matter far more is not what they were made of, but rather they looked like: A mad stone candidate had to look different, strange, not quite like stone—either through texture or color—that made it seem somehow organic in origin, something once living that had ossified. Its magic came from this singularity and belief.

Lincoln’s son Robert lived to be 82 years old—a mad stone success story. Most believed that a functional mad stone was infallible—they always worked, if operated properly. The few times a mad stone failed, it was because of a shortcoming of the patient. One man, bitten on the chin, died of rabies because his beard was too thick to properly accommodate a mad stone. Another person, bitten on the lips, accidentally swallowed some of the poison from the bite before the mad stone could take effect. In addition to Sutton’s prolific stone, the Milam Mad Stone of Collin County, Texas, supposedly saved more than 400 lives in its 47-year career, failing only twice. The Lightburne Stone was in use for over a century, with its owners stating it was called into action at least once a week, and more in the Dog Days of August. The papers were full of reports of successful mad stone treatments. “A Son of William Stittles, of Mecklenburg County, severely bitten on the leg by a mad dog, went to Charlotte to be treated by Mr. Butler,” noted The New York Times on June 19, 1885: “the stone adhered for two hours, and on a second application adhered for 30 minutes. The test was witnessed by a doctor and several citizens.”

Of course, all of this seems dubious now. Any kind of poison- or pathogen-sucking capillary function is impossible to replicate a scientific environment. Rabies viruses don’t appear as green scum. Milk can be naturally sticky without some kind of mystical suction. Given that rabies is inevitably fatal, it seems unlikely that the stones were so successful at curing people who had actually contracted the disease. Many may have just been bitten by animals without rabies. It appears that stories about effectiveness may have just been inflated with time, built on a confirmation bias from the few times people didn’t get sick and die. There are plenty of documented examples of mad stone failure: a family in Fort Worth in 1886, as reported in Science, a railroad worker in Missouri described in the Missouri Republican, a man in New Albany, Mississippi, who was bitten by a rabid dog in February 1886, used a mad stone in nearby Waterford, only to succumb to the disease two months later.

But the appeal of the mad stone is simple given the alternatives—painful cauterization or certain death—as a measure of power and control over an unstoppable foe. The explanation of the stone’s mechanism as drawing out the poison suggests that at least on some level believers thought it might be scientific rather than folk magic. Perhaps it is better to describe the belief in a mad stone’s powers not as anti-science so much as bad science.

Perhaps the clearest evidence that they didn’t ever work is the verdict of medical history: They more or less disappeared once Pasteur’s vaccine became widely available. But for a time, they compelled, particularly for their strange origin as amalgam of animal, vegetable, and mineral. In her 1966 book Purity and Danger, anthropologist Mary Douglas describes how humans create culture by classifying the world with taxonomies. Using the Book of Leviticus as an example, she suggests that those things that fit our scheme of categorization can be considered “clean.” Violation of that human-imposed order, however, might be “unclean.” It is the relationship of the sacred and the profane. “In that sense the universe is divided between things and actions which are subject to restriction and others which are not; among the restrictions some are intended to protect divinity from profanation, and others to protect the profane from the dangerous intrusion of divinity,” Douglas wrote.

In this light, the mad stone crosses boundaries by blurring our neat categorizations of life and non-life, the sentient and the inert, and that is the source of its healing power: Transgression.

This, perhaps, also explains why its primary purpose is to cure rabies, of all diseases—the one that reminds us, terrifyingly, that wildness is around us and in us, and welcomed into our home. A disease that transgresses the boundaries between nature and society requires an antidote that also straddles worlds.

Colin Dickey is the author of five books of nonfiction, including Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places, and, most recently, Under the Eye of Power: How Fear of Secret Societies Shapes American Democracy. He also hosts Atlas Obscura’s Monster of the Month.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook