Found: A 400-Year-Old Bible That Was Stolen From a Pennsylvania Library

It is one of hundreds of documents taken from the Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Library collection.

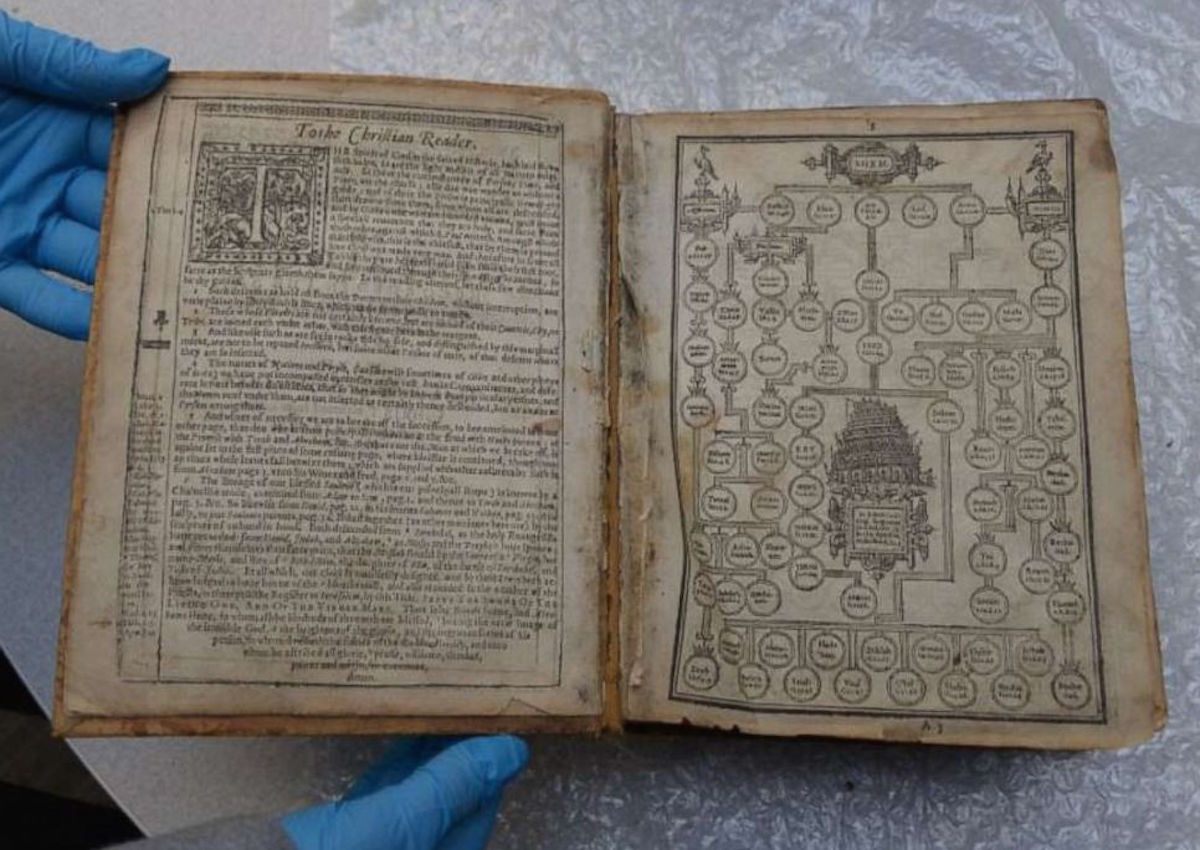

A 400-year old Bible has returned home to the Carnegie Library in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, after being declared stolen in 2017.

The theft was discovered during a routine appraisal of the library’s collections two years ago, in which it was determined that over 321 items, including books, maps, and photographs, had been stolen. Among the missing works were first editions of Isaac Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principe Mathematica from 1687 and a first edition of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

A former Carnegie Library archivist and a rare books dealer, who owns a local bookshop located just up the block from the library, have been accused of teaming up to funnel valuables, including the newly-returned Geneva Bible dating to 1615, from the library into the shop over a period from the late 1990s to 2016.

Geneva Bibles were mechanically printed and mass produced beginning in 1560. This was the version of the Bible that would have been available to William Shakespeare as well as working people. Protestant pilgrims would have brought this version with them to America. The stolen Bible had made its way to the American Pilgrim Museum in the Netherlands before the director discovered it was stolen and restored it to the Carnegie.

According to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, the recovered Bible is a variation of the Geneva referred to as a “Breeches Bible” because in its translation of Genesis it says that when Adam and Eve discovered they were naked, “they sewed figge tree leaves together, and made themselves breeches.” Those breeches became aprons in the King James translation, which appeared 51 years after the first Geneva Bible was printed.

“Conservative Protestants of the early 17th century preferred the Geneva Bible to the King James,” says David Szeczyk, proprietor of the Philadelphia Rare Books Company. “The significance of it is more mythological than it is real … it was a book that meant something to a large portion of the Protestant community.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook