Theia and the Collision That Gave Birth to the Moon

Evidence deep within the planet suggests that remnants of Earth’s catastrophic twin might still lie below.

Not long after the light first burst from the furnace at the heart of the realm, chaos reigned. Cosmic islands were careening into one another, fracturing and shattering, then melding and building. The most colossal orbs emerging from the pandemonium often had companions of rock or ice dancing around them. One stood largely alone, its fiery surface bubbling away, as another, Theia, approached at breathtaking speed. Soon a white-hot, soundless blast sent an eruption of diamantine matter out to the stars. It took an eon to see the outcome of this massive collision. In the end: a world of green and blue, and its pale companion, Selene.

As far as scientists can tell, this 4.5-billion-year-old creation story is no myth. Not long after the Sun formed, and the planets were beginning to take shape in the cloud of rock, dust, and gas around it, a protoplanetary object roughly the size of Mars (about half the size of Earth) slammed into our still-cooling, mostly molten planet. The collision jettisoned matter into space, mostly from Earth, as the protoplanet was almost entirely vaporized. The wreckage fell into orbit and, after a few million years or so, clumped together.

Scientists refer to the rogue impactor as Theia—an ancient deific entity from Greek mythology. Theia is the mother of Selene, known in Roman mythology as Luna, goddess of the Moon. And this story wasn’t haphazardly assembled by guessing astronomers. They put it together from fragments they could observe.

Lunar rocks have a chemical signature similar to many of Earth’s own volcanic rocks, suggesting a shared origin story. Radioactive matter within those rocks, which acts like a stopwatch that started running when the rocks formed, show that the Moon emerged very shortly after Earth did. And computer simulations demonstrate that you can get the Moon we know and love today if you slam a Mars-size projectile into a magma ocean–smothered Earth.

The one issue with this scientifically grounded saga is what happened to the culprit, Theia. To really establish the hypothesis, some of Theia would ideally be found—but it has long been thought that any surviving fragments were sent screaming into the neverending void billions of years ago. Part of the Moon is almost surely made of Theia matter, but it’s so thoroughly mixed into lunar chemistry that identifying it is all but impossible.

Perhaps, this last part of the scientific story needs to be updated.

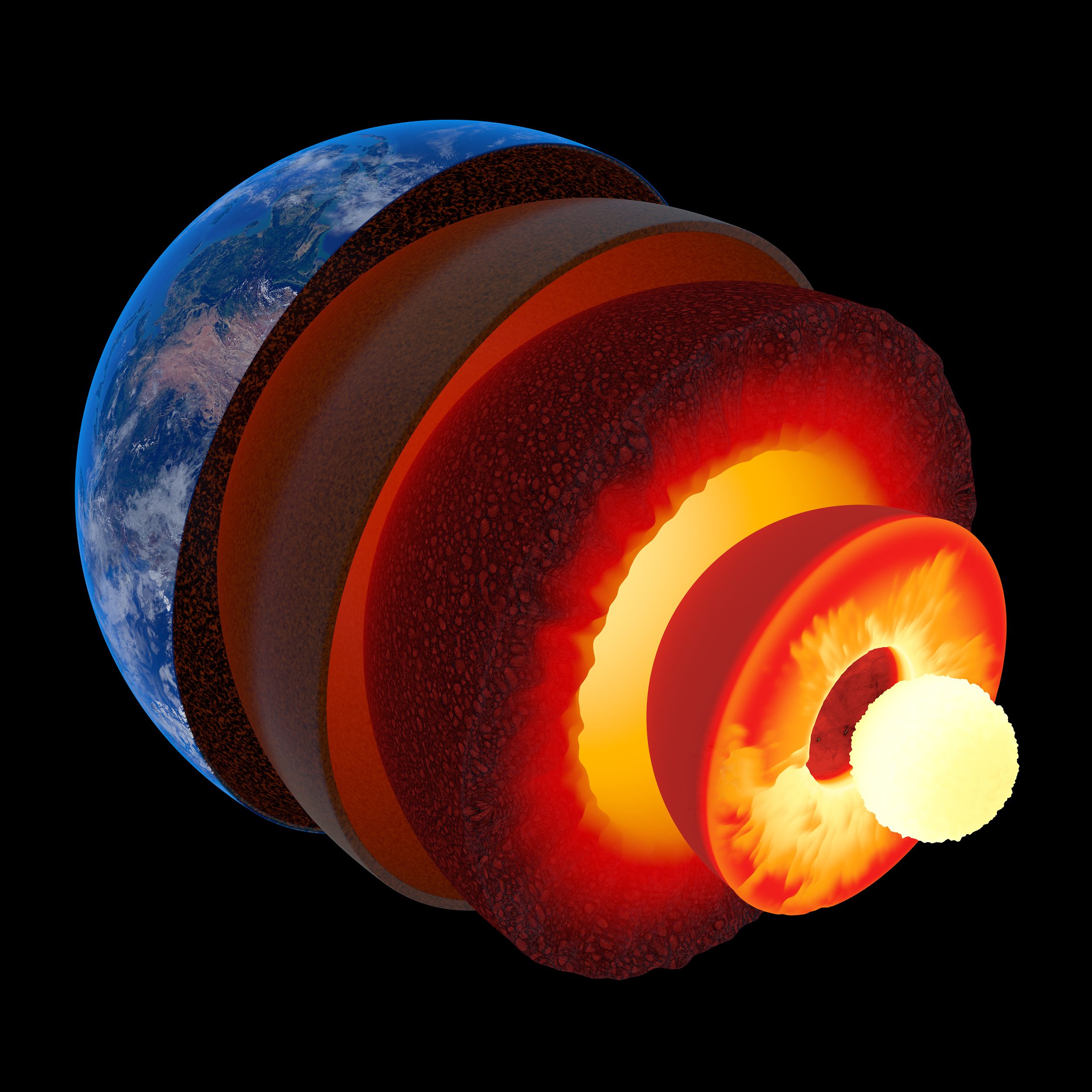

On the fringes of Earth’s core are two giant blobs—one beneath Africa, the other below the Pacific. Nobody is quite sure what they are. Seismic waves that pass deep through the planet reveal their existence, and their expansive size—continental, about 30 percent of the core-mantle boundary. But their chemistry, their nature, their provenance have been unclear since they were discovered decades ago.

Eventually, some scientists wondered: What if these two blobs were the carcass of Theia—or parts of it, at least?

Remarkably, according to a study published in Nature in November 2023, that looks to be true. Cutting-edge computer simulations of the hypothetical collision show that Theia’s outer crust would have been obliterated during the collision, but its putty-like molten mantle below would have partly survived. Some of it would have fallen into the magma-covered Earth. Being iron-rich and therefore very dense, these titanic shards would then have sunk to the greatest depths and settled atop the recently formed iron core, where they remain today.

The evidence is circumstantial, really; there is no way to extract unadulterated pieces of Earth that deep to confirm their identity. But this new study does align with the pile of other clues that suggests Theia was responsible for making the Moon—and the idea that pieces of this world-shattering, satellite-forging spectacle have been hiding inside Earth for billions of years is something close to magic.

Part of the appeal of the Earth and space sciences, for me at least, is how much they resemble myth—the gods and monsters of lore. These mercurial, towering creatures and figures were often said to exist outside of time and space, beyond our limited understanding. They went to war, betrayed each other, engaged in deception and combat that could make or break entire worlds.

In a way, volcanoes, earthquakes, comets, and asteroids aren’t that dissimilar; they ruled the solar system long before we arrived, and will continue to reign long after we’re gone. They have the power to create and destroy—they’re real primordial gods, only they’re made of rock, metal, and ice.

The making of planets, including Earth, is something that happens on such an epic scale that it’s difficult not to see it as a celestial stage for empyrean characters. The creation of the Moon fits this notion perfectly. Theia, satisfied that the Earth now had a companion to illuminate it dark nights, control its tides, and inspire countless stories, had performed her part. With that, she closed her eyes and sank into an unbroken slumber, dreaming of the stars.

As it happens, these blobs that may be the remains of Theia aren’t passive. The heat of Earth’s core-mantle boundary seems to be causing a stir within them, which has caused them to sprout fountains of superheated matter. Some of these plumes, over the course of millions of years, reach the base of tectonic plates, where they cook up batches of magma and fuel volcanic eruptions all over the world—including those that pour lava into the ocean and build islands from the waves.

Theia’s slumber isn’t so restful, after all—and it seems crafting the Moon wasn’t quite enough for one lifetime. So she became a writer of volcanic stories, her words pouring across the surface of the world, just waiting there until someone came along to read them.

At its heart, that’s what Earth science is about: turning myths into reality. And these stories are always grander and more fantastical than anything you’ll find in fiction, poetry, or legend.

Robin George Andrews is a doctor of volcanoes, an award-winning freelance science journalist, and the author of two books: Super Volcanoes: What They Reveal About Earth and the Worlds Beyond (2021), and the upcoming How to Kill an Asteroid: The Absurd True Story of the Scientists Defending the Planet (2024).

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook