About

During World War II, a blind brush maker named Otto Weidt had an idea to help some of the most vulnerable of the Jews who were being rounded up by Nazis in Berlin at the time. His secret weapon? His brush-making factory, which was equipped with machines designed to be used by the sightless.

Weidt's workshop was first opened in 1936, a few years into the Holocaust, and moved to 39 Rosenthaler Straße in 1940, just after the start of World War II. Since his brushes were purchased by the German army, his business was deemed important to the war effort. They were also sold as wedding presents on the black market.

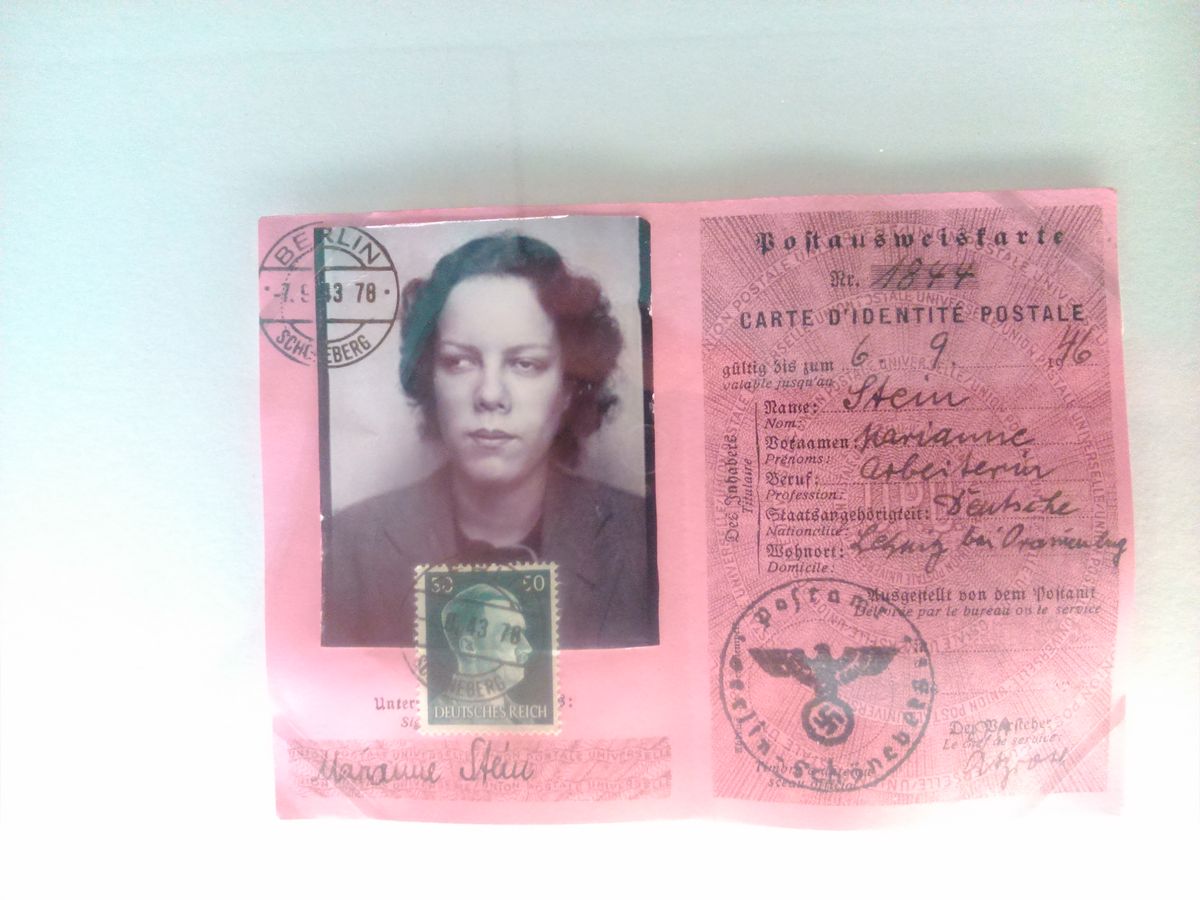

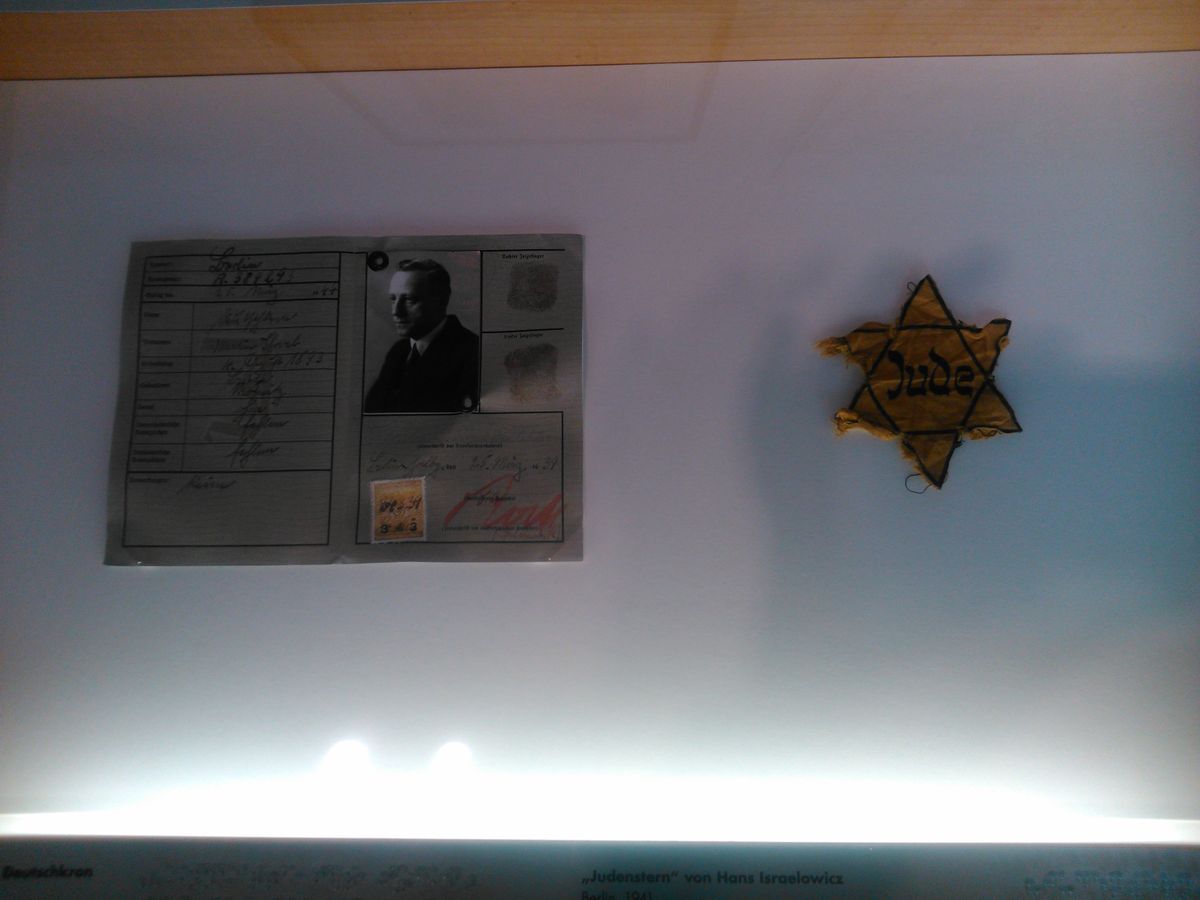

An anarchist and pacifist, Weidt hated the Nazis and resolved to be part of the resistance. His workforce was mostly made up of blind and deaf Jews, and throughout the war he employed every means he could to protect them. When members of the Gestapo came for his employees, he bribed them with fancy champagne, cigars, and perfumes he had purchased with the black market brush money. He falsified documents, including passports, for his workers, and toward the end of the war, when it was declared that Berlin should be completely Jew-free, he hid them in a room behind a backless cupboard in his workshop, and at locations around Berlin.

He even supported some from afar, sending food parcels to a young employee of his, Alice Licht, who had gone to join her deported parents, before helping her escape the death camps. It is believed he was in love with her, since part of his efforts to help her included traveling to Auschwitz. After the war ended, and in Weidt’s final years, he established an orphanage for concentration camp survivors.

Take special note of the collection of postcards, sent from the Theresienstadt concentration camps to Weidt's workshop. The message from Alice Licht's father, George, includes a coded message, referring to Weidt as a 'Potato Handler'. A remarkable statement smuggled past the censors, to highlight the deception the Nazis were employing in their propaganda campaign depicting Theresienstadt as a retirement facility.

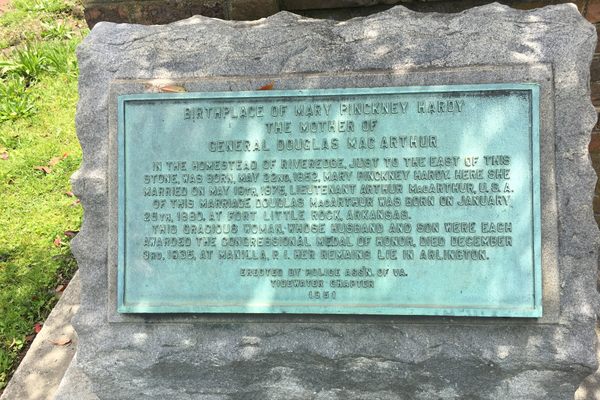

The museum that commemorates his efforts was first established by Museum Studies students from a local Berlin university. They found the building and set up an exhibit called “Blind Trust” in one of the rooms in 1999. With the help of one of the Jews that Weidt had employed and helped, Inge Deutschkron—by then an award-winning author and journalist who, in 1993, had arranged for a plaque to be placed on the building commemorating Weidt’s efforts—set up a foundation to preserve the space.

The museum presents the rooms as they were in the '40s, with brushes and brush making machines on display, and also features pictures and documents from the time. A video of interviews with survivors who were helped by Weidt is an emotional highlight. The building also houses the Anne Frank Center and the Silent Heroes Memorial Center.

In 2001, the site became an affiliate of the Jewish Museum in Berlin, and in 2004 the building was purchased and placed in the care of the German Resistance Memorial Center Foundation, which preserves the memories of individuals and organizations that resisted Hitler and the Nazis in whatever way they could, whether hiding Jews or trying to assassinate Adolf Hitler.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

It's located in a courtyard in the Haus Schwarzenberg alley, entered beside Café Cinema. It's open daily and there's free admission.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

April 3, 2017

Sources

- http://www.museum-blindenwerkstatt.de/en/first-of-all/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Otto_Weidt

- http://www.visitberlin.de/en/spot/museum-blindenwerkstatt-otto-weidt

- http://www.berlin.de/en/museums/3109648-3104050-museum-blindenwerkstatt-otto-weidt.en.html

- https://www.lonelyplanet.com/germany/berlin/attractions/museum-blindenwerkstatt-otto-weidt/a/poi-sig/1104124/359364

- http://www.orte-der-erinnerung.de/en/institutions/institutions_liste/museum_otto_weidt/druckversion.html

- https://www.museumsportal-berlin.de/en/museums/museum-blindenwerkstatt-otto-weidt/

- http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/the-blind-hero-new-film-tells-of-unsung-schindler-otto-weidt-who-saved-jews-from-nazi-death-camps-9042395.html