About

"The gates of hell are open night and day; Smooth the descent, and easy is the way: But to return, and view the cheerful skies, In this the task and mighty labor lies... "

—Aeneid, book VI, Virgil

Virgil famously described a cave with a hundred openings as home to one of the most famous prophetesses of ancient legend—the Cumaean Sibyl. Written in 19 B.C., the Aeneid chronicles the adventures of Trojan warrior Aeneas, including his encounter with a mysterious ancient fortune teller. It was said this oracle, or sibyl, dwelt in the mouth of a cave in Cumae, the ancient Greek settlement near what is now Naples.

"A spacious cave, within its farmost part, Was hew'd and fashion'd by laborious art Thro' the hill's hollow sides: before the place, A hundred doors a hundred entries grace; As many voices issue, and the sound Of Sybil's words as many times rebound."

In the poem, the sibyl acts as a kind of guide to the underworld, to which Aeneas must descend to seek the advice of his dead father Anchises and to fulfill his destiny.

This was not the first appearance of the Cumaean Sibyl in art and literature, nor the last. The most famous story dates to the time of the last Roman King, Tarquinius Superbus, around 500 B.C.

According to the story, the sibyl approached the king with nine books of prophesy, collected from the wisest seers, available to the king for a very dear price. The king haughtily refused her price. In response, the sibyl burned three of the books, then offered the remaining six books at the original high price. Again he refused. Of the remaining six books, she threw three more onto the fire, and repeated her offer of the final three books, at the original price. Afraid of seeing all the prophesy destroyed, he finally accepted.

These books, which foretold the future of Rome, became a famous source of power and knowledge and were stored on the Capitoline Hill in Rome. In 82 B.C., the books were destroyed in the burning of the Temple of Jupiter, and in 76 B.C. envoys were sent around the known world to rebuild the books of prophesy. The new books managed to make it until 405 A.D., near the end of the Roman Empire.

The Cumaean Sibyl would later appear in the works of Ovid, on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, painted by Michelangelo, in Dante's Inferno, and in the poetry of T.S. Elliott. In his Metamorphosis (book 14), Ovid tells of the sibyl's sad end. She ended up on the losing side of a deal with the god Apollo. Apollo sought her virginity, offering her a wish in exchange:

"I pointed to a heap of dust collected there, and foolishly replied, 'As many birthdays must be given to me as there are particles of sand.' For I forgot to wish them days of changeless youth. He gave long life and offered youth besides, if I would grant his wish. This I refused..."

Because of her refusal, he granted her wish in word, but not in essence, and she lived a thousand years without eternal youth. When Aeneas met her, she was 700 years old and still a virgin.

According to tradition she would have sung her prophecies, or written them on oak leaves which she would leave at the mouth of the cave.

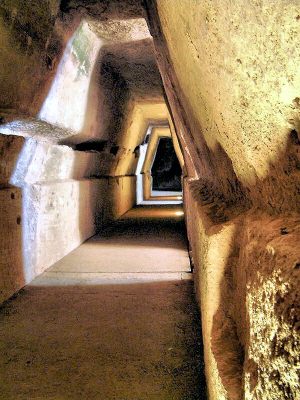

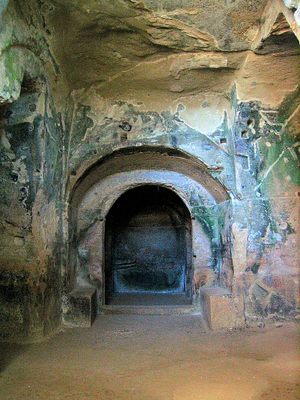

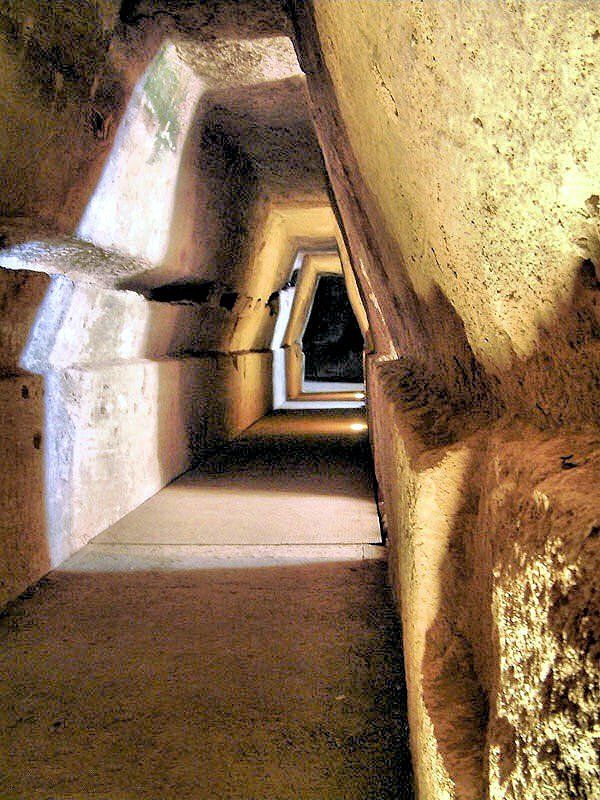

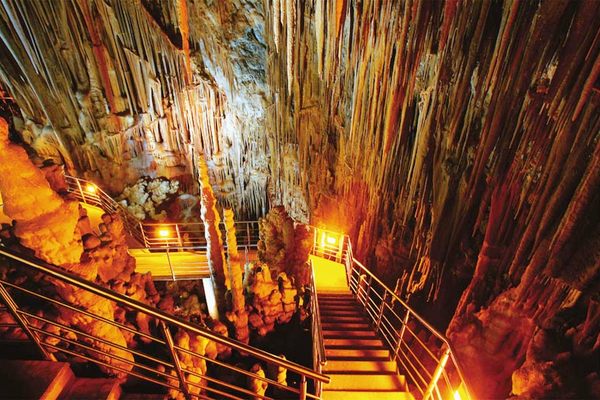

Searches for the famous cave described by Virgil were undertaken in the Middle Ages, and there are other nearby niches that have also been named "the Sibylline grotto," including one closer to Lake Averno. The "official" Cave of the Sibyl was uncovered more recently, in 1932, by archaeologist Amedeo Maiuri, who was in charge of excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum for many years. He was also responsible for the excavation of the Villa Jovis on Capri. It is now thought to be of a later vintage than the cave described by Virgil, but a plaque by the entrance still labels it as Sibyl's cave.

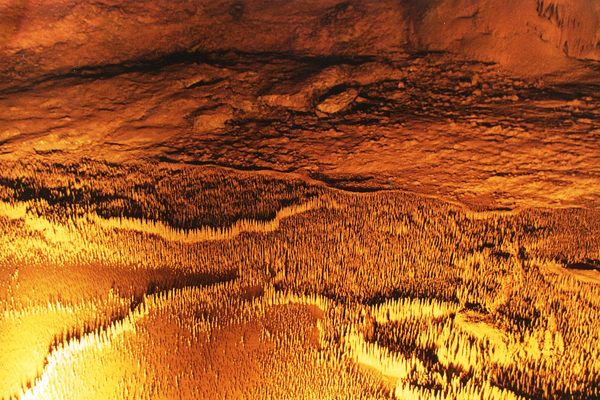

The shape of the cave indicates that it might have been Etruscan in origin, possibly cut by the Etruscan slaves of the conquering Romans around the 6th century B.C. (about the time of the story of the Sibylline Books). The passage has many entrances, though not the hundred mentioned, and is 5 meters high by 131 meters long, with several side galleries and cisterns.

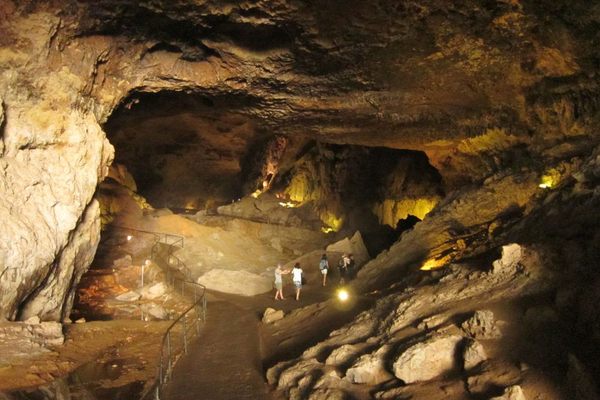

The Sibyl's cave is very close to other famous Roman caves which lead to Lake Avernus, including the Crypta Romana and the enormous Grotta di Cocceio, a tunnel dug through the mountain to access the Lake, which is large enough for chariots to pass through. In the poem, Aeneas reaches the underworld at Lake Avernus by passing first through the Sibyl's cave, but in reality he would have needed to duck into a different one.

All of these literal gateways into the realm of shades have reinforced the long-held associations of this area of Southern Italy with the mythical underworld. The volcanically active region around Naples is known as the Campi Flegrei, or "Feiry Fields." Avernus was named as the opening to Hades by Virgil, but the area's bubbling sulphur pits and volcanic, brimstone-scented islands were also mentioned by early writers as portals to hell.

The Antro della Sibilla is now part of the Cumae Archaeological Site (Parco Archeologico di Cuma).

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

Northwest of Naples.

Flavors of Italy: Roman Carbonara, Florentine Steak & Venetian Cocktails

Savor local cuisine across Rome, Florence & Venice.

Book NowCommunity Contributors

Added By

Published

December 31, 2009

Sources

- http://www.culturacampania.rai.it/site/en-GB/Cultural_Heritage/Archaelogical_areas_and_Nature_parks/Scheda/cuma_parco_archeologico.html?link=storia

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cumae

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cumaean_Sibyl

- http://homepage.mac.com/cparada/GML/Sibyl6Cumaean.html

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aeneid

- http://classics.mit.edu/Virgil/aeneid.6.vi.html

- http://faculty.ed.umuc.edu/~jmatthew/naples/blog22.htm#jul31

- http://andromeda.umwblogs.org/2009/01/14/research-in-cumae-day-2-48-hours-remain/

- http://www.philipcoppens.com/cumae.html

- http://www.napoliunderground.org/en/component/content/article/56-artificial-cavity/2206-the-sibyls-cave.html