DNA Says ‘Yeti’ Evidence Comes From Bears, But Will Believers Be Convinced?

One expert sees the value in maintaining a little mystery.

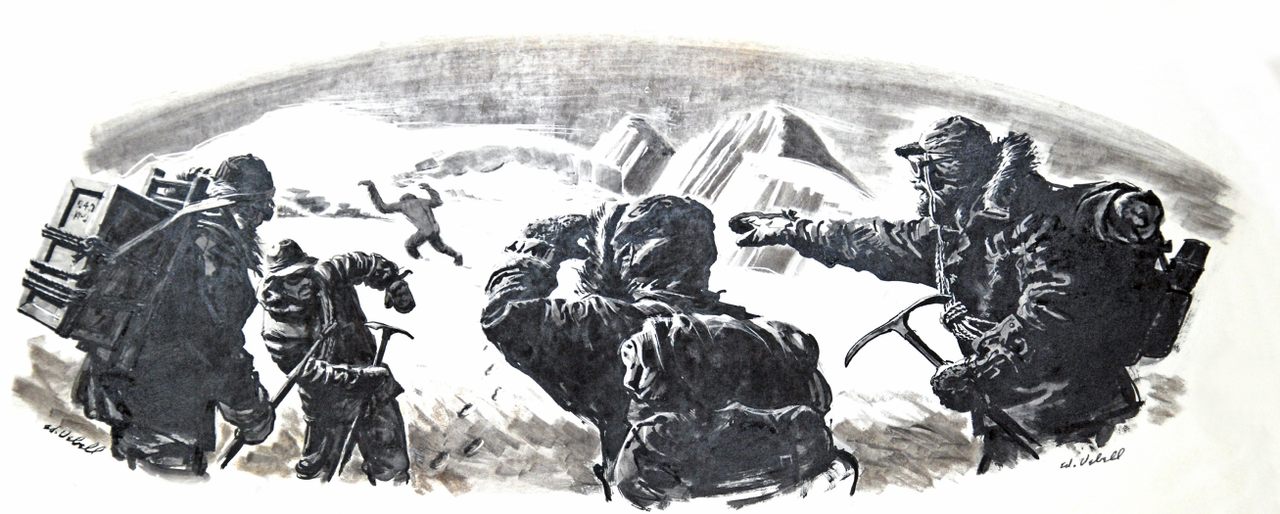

When Daniel Taylor gives lectures on the relationship between humans and the wild, he often clambers out on stage clad in a Chewbacca costume. It’s not quite a yeti suit, but it does the job. He then unzips the head-to-toe shag to reveal the human underneath. Taylor, author of the book Yeti: The Ecology of a Mystery, released last month, has spent upwards of six decades on the trail of the humanoid creatures that are central to the folklore of the Himalayas. As the conservationist and ecologist explains in the book, he believes he’s found the explanation for the snowy footprints they’re reported to have left in the snow, and the culprit is large, furry, and decidedly non-mythical.

Now a new study, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, is supporting his conclusion with DNA. The research involved assessing DNA from 24 samples of hair, bone, skin, and feces reported to have come from yetis or other unidentified mountain dwellers. The samples, collected around the Himalayas or the Tibetan Plateau and housed in museums, zoos, and private collections, were then compared with the newly sequenced mitochondrial genome for the Himalayan brown and black bears. “Our findings strongly suggest that the biological underpinnings of the Yeti legend can be found in local bears, and our study demonstrates that genetics should be able to unravel other, similar mysteries,” said the lead scientist Charlotte Lindqvist, of the University at Buffalo, in a statement.

It’s definitely not the first time that DNA has been used to affirm or debunk the yeti legend.

One frenzied episode began in 2014, after a team at Oxford University and the Museum of Zoology in Lausanne, Switzerland, solicited submissions of alleged yeti hair. They were able to chuck more than a dozen of the 57 submissions right away—some were plant material, glass, or other “obvious non-hairs.” Thirty-seven samples, spanning 50 years, passed the eye test, and DNA analysis concluded that a couple of the samples might represent some kind of Paleolithic polar bear. The findings were swiftly disputed by other academics, who charged that the researchers had misinterpreted a DNA sequence to come up with an unprecedented creature instead of a more plausible, extant source. Lindqvist and her collaborators acknowledge the shortcomings of the previous paper, and write that theirs is “the most rigorous analysis to date of samples suspected to derive from anomalous or mythical ‘hominid’-like creatures.”

Taylor hasn’t spoken to Lindqvist and her team, but appreciates that their work seems to jibe with his own findings. In his book, Taylor makes the case that the tree-dwelling Asiatic black bear was responsible for the most famous yeti tracks, in particular the ones photographed by mountaineer Eric Shipton in 1951. Taylor managed to recreate those prints with the help of a tranquilized Asiatic black bear at India’s Kamla Nehru Zoological Garden. (Its thumb-like digit, which helps the creature cling to trunks and branches, explains the thumb-like indentation in Shipton’s photos that sparked so much speculation.) But Taylor stresses that DNA evidence, despite its iron-clad reputation, is only one part of the story.

For example, he points out that the raw material in the study could have come from anywhere, and may not have been associated with other yeti evidence. One sample in the new study turned out to be from a dog, and a hair in the earlier study had once graced a raccoon. “The method is precise, but material that went into the machine is highly questionable,” Taylor says. “What evidence do we have that is absolutely, conclusively yeti? That’s only footprints.”

Beyond the question of whether footprints and hair are reliable data points, Taylor poses a bigger, more slippery quandary, which started to snowball for him as he conducted his search. Do we need to poke and prod the legend in the first place? Is the puzzle of the yeti one we really want to solve and shelve, or is the uncertainty important to who we are?

In some respects, myths such as the legend of the yeti are designed to be unverifiable, Taylor says. He cites the uneasy relationship between wanting tangible, quantitative facts to make sense of the world and the gnawing desire to be awed by it. Out in nature—beyond the Anthropocene’s urban parklets, in huge, humbling landscapes—there’s magic. To that end, Taylor has helped establish protected areas in those expanses thought to be “anomalous hominid” stomping grounds. In the introduction to his book, Taylor invokes, as an antidote to a nature-free life, Rudyard Kipling’s instructions to set out wide-eyed and ready for anything:

Go and look behind the Ranges–

Something lost behind the Ranges.

Lost and waiting for you. Go!

That’s why Taylor thinks that DNA evidence is unlikely to make humans abandon the possibilities of unconquered wilderness. He feels them, too. “I know the footprints, but I haven’t answered the enigma,” he says. “There is no mystery in my mind about any of the evidence, but there’s mystery in my heart.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook