The World’s Oldest Botanical Gardens

Ever since most of us stopped being nomads and settling in cities and towns, civilizations have set aside green spaces dedicated to plants, flowers, and the general enjoyment of nature. From the simple to the complex, gardens seem to embody the aesthetic tastes of the cultures that crafted them.

In this rundown of botanical gardens around the world, we take a look at the oldest of these botanical gardens, and explore a bit of their unique histories.

ORTO BOTANICO DI PADOVA

Padova, Italy

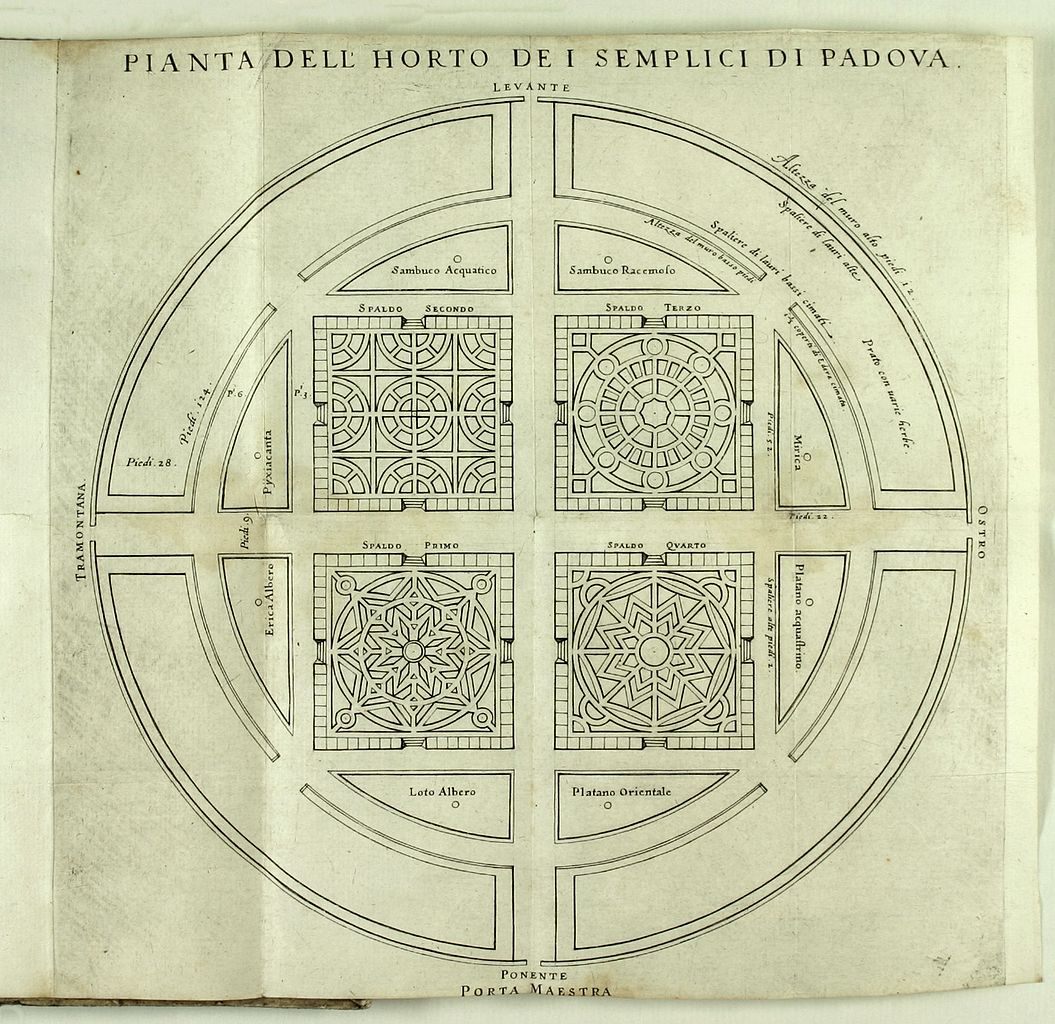

16th-century illustration of the Orto Botanico di Padova (via Esculapio/Wikimedia)

16th-century illustration of the Orto Botanico di Padova (via Esculapio/Wikimedia)

Established in 1545 by the Senate of the Venetian Republic, the Orto Botanico di Padova can be proud of being the world’s oldest academic botanical garden that is still in its original location. With over 6,000 types of plants, the garden is committed to nurturing medicinal flora that produce natural remedies. Lookalike and poisonous plants are also grown here, so that students can distinguish the useful plants from the harmful and false ones. The central fountain is fed by a hot spring that runs underneath the garden, which keeps the aquatic plants healthy and happy.

For its valuable plants, thieves would often scale the circular walls around the garden, risking fines, exile, and jail time if they were caught.

Botanical garden of Padua (photograph by Rollroboter/Wikimedia)

Botanical garden of Padua (photograph by Rollroboter/Wikimedia)

Botanical garden of Padua (photograph by Rollroboter/Wikimedia)

Botanical garden of Padua (photograph by Rollroboter/Wikimedia)

16th-century map of the Botanical garden of Padua, by Girolamo Porro (via uni-mainz.de)

GARDENS OF VERSAILLES

Versailles, France

Latona Fountain with the Grand Canal in the background (photograph by Kal-El/Wikimedia)

Latona Fountain with the Grand Canal in the background (photograph by Kal-El/Wikimedia)

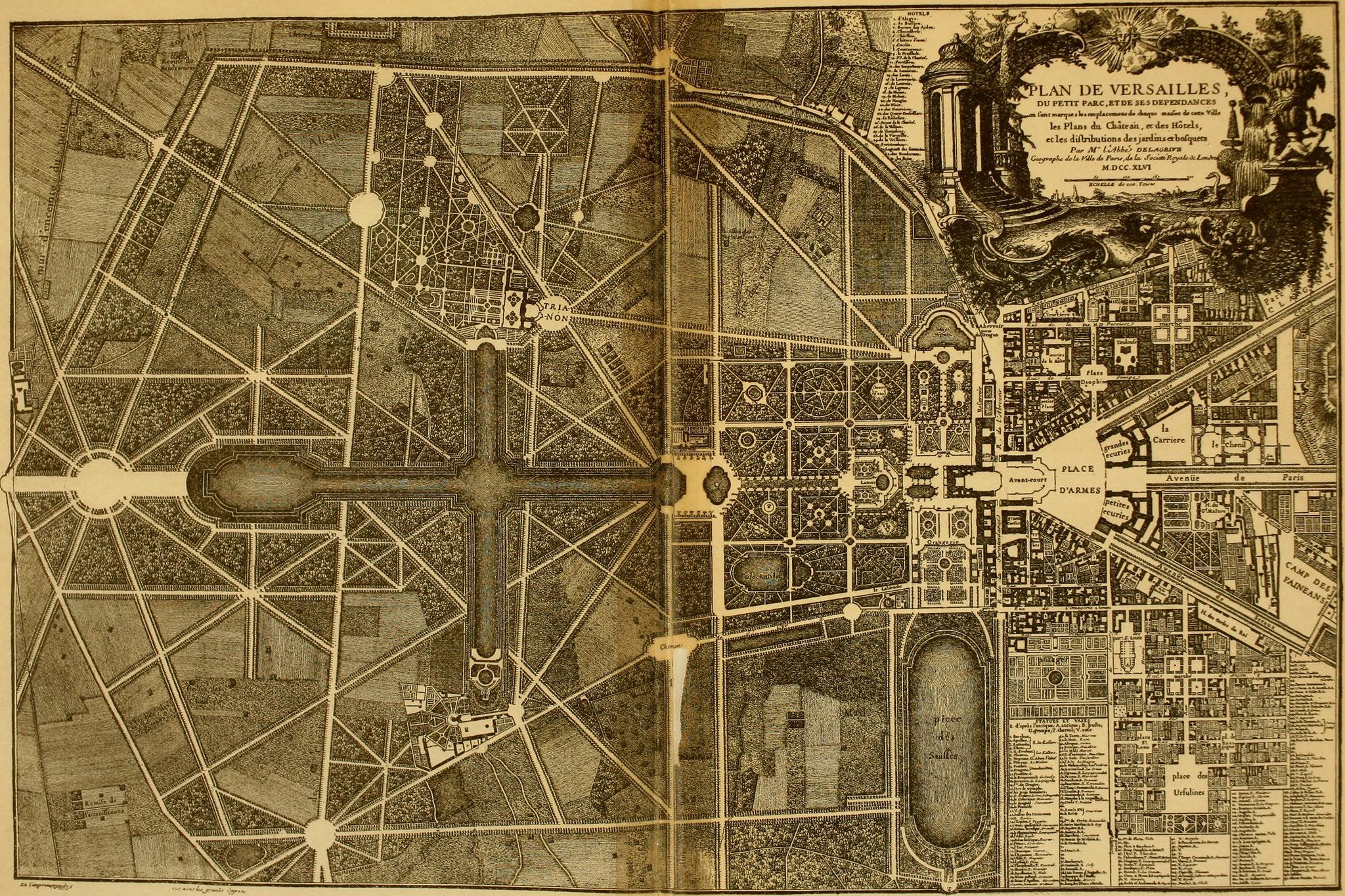

In 1661, Louis XIV chose André Le Nôtre to begin the 40-year task of constructing the grand gardens of Versailles. Located behind the famous Versailles Château, the 800 hectares of classic French Garden-style are now visited by over six million people a year.

A Grand Canal bisects the gardens for nearly a mile, and the massive waterway also served as a convenient place for boating parties. Extensive numbers of fountains flow throughout the gardens, and many follow the theme of Apollo and solar imagery as metaphors for Louis XIV, the Sun King. A key element is the Grotte des Bains d’Apollon, which is a massive sea cave decorated with shell-work. Statutes of the sun king attended by nereids are surrounded by elaborate fountains.

Map of Versailles from 1905 (via Internet Archive Book Images)

Map of Versailles from 1905 (via Internet Archive Book Images)

Bassin d’Apollon, one of the fountains in the gardens of Versailles (photograph by Allison Meier/Atlas Obscura)

Bassin d’Apollon, one of the fountains in the gardens of Versailles (photograph by Allison Meier/Atlas Obscura)

Panoramic view of the Versailles Gardens (photograph by uggboy /Wikimedia)

Panoramic view of the Versailles Gardens (photograph by uggboy /Wikimedia)

THE LOST GARDENS OF HELIGAN

Mevagissey, England

The Italian area in the Lost Gardens (photograph by Chris Wood/Wikimedia)

The Italian area in the Lost Gardens (photograph by Chris Wood/Wikimedia)

Known in Cornish as the Lowarth Helygen, the Lost Gardens of Heligan near the fishing village of Mevagissey were planted by the Tremayne family in the middle of the 18th century. Fallen into disrepair after the First World War, the estate later restored its botanical holdings to their full glory in the 1990s.

Visitors to the Lost Gardens can admire Europe’s only pineapple pit — an ingenious way discovered by Victorian-era gardeners to coax pineapples from colder environs. The pit consists of shallow trenches covered with glass and connected with outer troughs filled with up to 15 tons of fresh horse manure. This rich decomposition radiates heat through the pit walls, and the pineapples are kept toasty in the heart of the troughs.

While most of the gardens are potagers or ornamental, the Lost Gardens also have vast slopes of valleys that contain much wilder plants, as well as more contemporary sculptures of lounging giants. These areas are named the Jungle and the Lost Valley, and much of the garden drains through it.

The pineapple pit at the Lost Gardens (photograph by Deb Collins/Flickr)

The pineapple pit at the Lost Gardens (photograph by Deb Collins/Flickr)

The Lost Gardens of Heligan (photograph by Robert Pittman/Flickr)

The Lost Gardens of Heligan (photograph by Robert Pittman/Flickr)

Sleeping Goddess of the Lost Gardens (photograph by Loco Steve/Flickr)

Sleeping Goddess of the Lost Gardens (photograph by Loco Steve/Flickr)

THE DURBAN BOTANIC GARDENS

Durban, South Africa

Durban Botanic Gardens (photograph by Alf Igel/Flickr)

Durban Botanic Gardens (photograph by Alf Igel/Flickr)

The oldest thriving botanical gardens on the African continent are in Durban, South Africa, in KwaZulu-Natal province (“the garden province”). Intended to supply the Kew gardens in England with economically valuable and novel plants, the Durban Botanical Gardens were set up in December of 1849. Cash crops like sugar cane, coffee, pineapples, and tea were quickly established.

One of the unique structures at the Durban gardens is the Living Beehive, a dome structure with walls incorporating dense mats of creeping vines. This allows enough air to circulate into the rich forest and wetland growths of the interior. Check out the Living Hive pictures here (courtesy of the garden designers).

The Durban gardens now host local music bands, indigenous plant fairs on an international level, and Victorian tea parties.

Durban Botanic Gardens (photograph by Wayne77/Wikimedia)

Durban Botanic Gardens (photograph by Wayne77/Wikimedia)

Durban Botanic Gardens (photograph by YattaCat/Flickr)

Durban Botanic Gardens (photograph by YattaCat/Flickr)

SIGIRIYA GARDENS

Dambulla, Sri Lanka

The Lion Gate that leads to the gardens (Image by Cherubino via Wikimedia)

The Lion Gate that leads to the gardens (Image by Cherubino via Wikimedia)

As the site of an ancient palace from the Fifth century BC, Sigiriya in Sri Lanka is one of the oldest instances of urban planning. The Lion Rock that dominates the landscape here overlooks the ruins of the royal quarters that also served as a Buddhist monastery until the end of the 14th century.

Extensive terraces of gardens are cut into the rock, and there are many cisterns in the cliffs that once held water for the rich plant life. The water gardens feature an ancient style called Charbagh, which is a quadrilateral garden divided by flowing water or paths into four smaller parts.

Lion Gate at Sigiriya (photograph by Paul Mannix/Flickr)

Lion Gate at Sigiriya (photograph by Paul Mannix/Flickr)

Stairway on Lion’s rock (photograph by Malcolm Browne/Flickr)

Stairway on Lion’s rock (photograph by Malcolm Browne/Flickr)

A view of Sigiriya Rock as seen from the Fountain Gardens (photograph by Marco Lazzaroni/Flickr)

Bird’s eye view of the Sigiriya gardens (photograph by Ela112/Wikimedia)

Bird’s eye view of the Sigiriya gardens (photograph by Ela112/Wikimedia)

THE CANGLANG PAVILION

Suzhou, China

Moon Gate at Canglang Pavilion (photograph by 猫猫的日记本/Wikimedia)

Moon Gate at Canglang Pavilion (photograph by 猫猫的日记本/Wikimedia)

Song Dynasty poet Su Shunqing set up the Canglang Pavilion in 1044 BC on the grounds of what used to be an imperial flower garden. The name of the gardens derives from an ancient poet, and was used by Su to express his displeasure at being removed from political office: ”If the Canglang River is dirty I wash my muddy feet; If the Canglang River is clean, I wash my ribbon”.

Many garden buildings on this UNESCO World Heritage site are similarly inspired by poetry and literature. For example, the Fish Watching Place is a pavilion overlooking the water, and is named after a famous dialectic by Zhuang Zi about fish. Other structures include the Temple of 500 Sages, the Water Pavilion of Lotus Blossoms, and the Realm of Yaohua.

Canglang Pavilion (photograph by Chinatravelsavvy/Wikimedia)

Canglang Pavilion (photograph by Chinatravelsavvy/Wikimedia)

Canglang Pavilion (photograph by Chinatravelsavvy/Wikimedia)

Canglang Pavilion (photograph by Chinatravelsavvy/Wikimedia)

FLOATING GARDENS OF LAKE XOCHIMILCO

Xochimilco, Mexico

A colorful trajinera boat traversing the floating gardens (Image by Protoplasma Kid via Wikimedia)

A colorful trajinera boat traversing the floating gardens (Image by Protoplasma Kid via Wikimedia)

Chinampas date back to 1150 BC as a Mesoamerican method of using small floating gardens on shallow lake beds or made-made canal systems. The Aztec Empire flourished using this floating agriculture until the Spanish arrived in the New World. Only about 5,000 chinampas exist now.

In Xochimilco, Mexico, the chinampas are still in use by farmers, though the canals have been much reduced from their previous sprawl over most of the Valley of Mexico. The water levels continue to drop each year due to population demands in Mexico City. Today, visitors can ride on colorful gondalas called trajineras on tours of the gardens.

The most famous floating garden in Xochimilco belonged to a local resident named Julián Santana Barrera. A loner by nature, he was known for collecting creepy dolls as they floated by and hanging them from branches to appease the spirit of a dead girl he discovered on the island. He often commented to curious visitors that he believed the dolls would awaken at dusk to kill animals. The mass collection of dolls were discovered in the early 1990s when the area had to be cleansed of a surge in water lily growth. Julián passed away in 2001, but his dolls continue to keep away evil spirits.

Island of the Dolls in Xochimilco (photograph by Amrith Raj/Wikimedia)

Island of the Dolls in Xochimilco (photograph by Amrith Raj/Wikimedia)

Island of the Dolls (photograph by Esparta Palma/Wikimedia)

Island of the Dolls (photograph by Esparta Palma/Wikimedia)

Discover more of the world’s incredible gardens on Atlas Obscura >

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook