Why Irish Dirt Is Worth Millions of Dollars

The luck o’ the Irish—it’s all buried in their soil. (Photo: TinnaPong/shutterstock.com)

The luck o’ the Irish—it’s all buried in their soil. (Photo: TinnaPong/shutterstock.com)

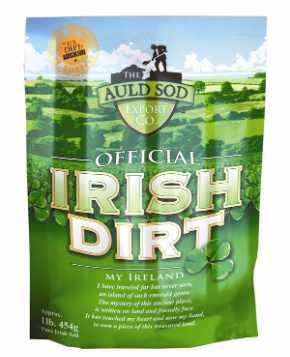

Who needs to hunt for leprechauns when a one-pound baggie of lucky Irish dirt only costs $11.40?

Official Irish Dirt is normally sold in the U.S. in small pouches or canisters—sometimes with shamrock seeds thrown in for extra luck—but for some folks, that’s not enough. One 87-year-old lawyer hailing from the Emerald Isle spent $100,000 worth of Irish dirt to fill his American grave, while a man originally from County Cork purchased enough Irish-sourced earth to spread under his freshly constructed house in New England, a total investment of $148,000. Funeral directors and florists order the dirt in bulk, while others just need enough to sprinkle around a tree or on a casket to connect with their land of birth.

Desire for the “auld sod” of their homeland is apparently enough to bring Irishmen abroad to tears. And when businessman Alan Jenkins saw those tears, back in the mid-’90s, he saw an untapped opportunity and a market unmet.

It all began when Jenkins, an Irish immigrant then in his mid-50s, found himself at a gathering in Florida of the Sons of Erin, a nonprofit dedicated to promoting Irish heritage. “The only thing everyone [at the meeting] would give their right arm for was a drop ‘of the auld sod’ to put on top of their casket,” Jenkins told The New York Post. It seemed that while Irish-Americans had been able to bring over their families, their schools, their churches, and their pubs, the one thing they didn’t have was their dirt—and Irish dirt, it turns out, holds a special place in Irish hearts. Men would sometimes tear up, said Jenkins, expressing how deeply they wished for a bit of true Irish dirt to be spread over their caskets. It got Jenkins thinking.

Oh, the sweet earth of the Emerald Isle! (Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain)

Normally, there are bans on soil imports in order to prevent foreign critters from infiltrating domestic crops. But the U.S. Department of Agriculture has actually made two special exceptions, issuing special permits for import to Irish dirt and Israeli dirt (available wholesale from the company Holy Land Earth).

Securing that permit took Jenkins years of contemplation and effort.

Five years after his Sons of Erin encounter in Florida, Jenkins got in touch with an industrial chemist, who thought he might be able to cleanse the dirt enough to satisfy trade regulations. Though the chemist soon decided it was impossible, Jenkins wasn’t quite ready to give up.

In 2006, he met Pat Burke, a young, Irish-American agricultural scientist. Together, after petitioning both the U.S. Customs Department and the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, they patented a method of sanitizing Irish dirt that met American regulations. When they got the green light, they committed themselves full time to the booming business of redistributing earth. Their company became the Auld Sod Export Company and their product, “Official Irish Dirt.” Initially, Jenkins had wanted to collect dirt from each of Ireland’s 32 counties so that buyers could choose the dirt closest to their ancestral home, but that proved a bit too laborious, so they began sourcing from a two-acre field in Tipperary county in the middle of the Golden Vale.

A 1 lb pouch of dirt straight from “My Ireland.” (Photo: Joe’s Plant Nook)

Later that same year, their first shipment reached a warehouse in Long Island, New York, and the company’s website crashed within 15 minutes of launching. Jenkins reported receiving calls all week from folks interesting in starting up franchises. Auld Sod Export Co. started digging up dirt more rigorously and ramping up shipments to its distribution center in Williston, Vermont. They started buying and renting other plots of Irish earth to keep up with demand.

While many Irish immigrants wanted dirt from home to bless their burials, florists were equally interested in ordering the topsoil for planting flowers and shamrocks. There’s also an Irish tradition of planting a tree to mark the birth of a newborn, and many wished these trees could set their roots in Irish soil.

Soon, Jenkins and Burke were receiving online requests from Irish folks all over the world. The lore of lucky Irish dirt even made its way to China, where non-Irish Chinese began requesting shipments of the trending soil, too. With business booming, Jenkins and Burke chose to donate 80% of the company’s multi-million-dollar profits to charities in the U.S. and Ireland.

Official Irish Dirt is great for growing authentic Irish shamrocks. (Photo: Supportstorm/Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

However nine years later, the Irish dirt business seems to have all but ground to a halt. If you’re still hoping to buy some Official Irish Dirt, there’s a limited stock left, sold by sites like Joe’s Plant Nook and Sullivan’s Irish Alley. Business has definitely slowed down, and retailers say that the Auld Sod Export Company has gone out of business entirely. Its website is still available, but their customer service number now greets you with a Rent-a-Car recording. Luckily, if you can get your hands on some of the dirt, it’ll last you a while; the “best before” date on the bags is August 9, 2162.

It makes one wonder what happened—did folks in Ireland start noticing massive craters appearing in their fields and start to complain? Did they start demanding their dirt remain domestic? Did someone decide that the amount of earth being shipped over the ocean was getting excessive? Or did Jenkins and Burke decide they had other fields to sow and fish to fry?

If there’s one thing that’s obvious, it’s that dirt is nothing to be taken lightly.

Or as the poem on pouches of Official Irish Dirt would tell you:

I have traveled far but never seen,

an island of such emerald green,

the mystery of this ancient place,

is written on land and friendly face.

It touched my heart,

and once my hand,

and now I’m surrounded,

by my treasured land.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook