Why Did ‘Share a Coke’ Blacklist These 24 Countries?

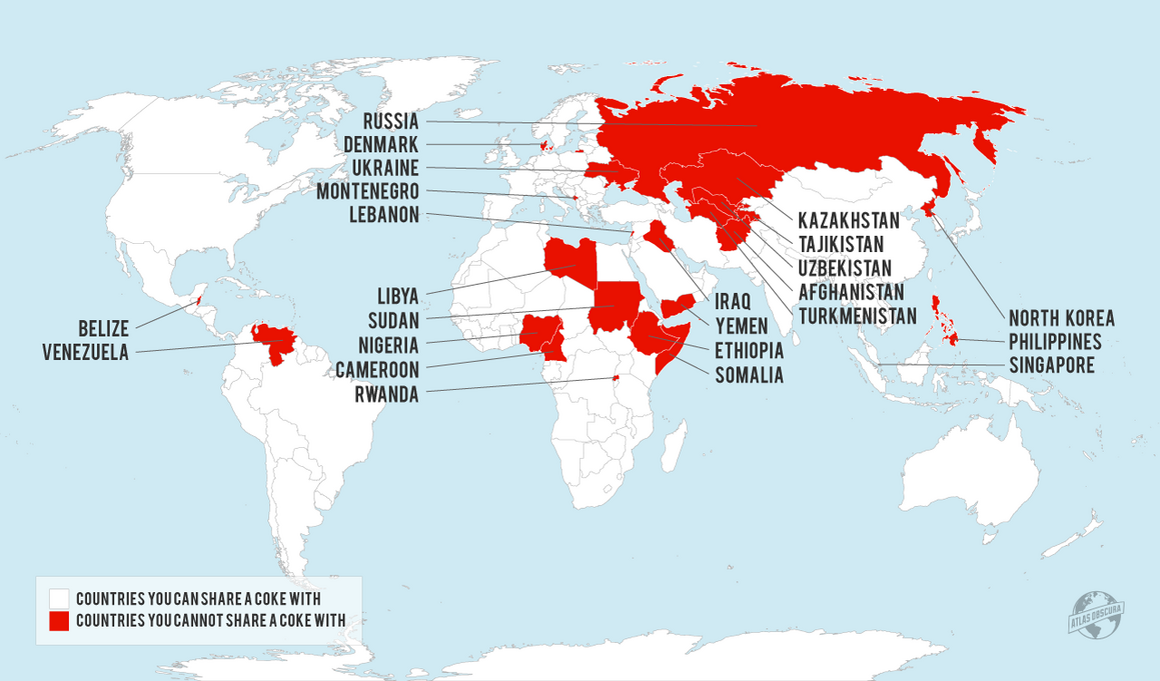

A map detailing all of the countries with which you can and cannot Share a Coke. (Image: Atlas Obscura)

At this point, you’ve likely seen billboards, subway posters, or television commercials advertising Coca-Cola’s newest marketing gambit: the “Share a Coke” campaign.

For this new promotion, the company has replaced the swirly brand name emblazoned on its beverage labels with a variety of common monikers. Instead of a line of garden-variety Coca-Colas, supermarket shelves now boast bottles named, for instance, “Aaron,” “Whitney,” and “Zach.”

“Share a Coke” was born in Australia and has since been unveiled in over 80 countries, including China, the U.K., and the good old U.S. of A. Last year, the company added a new twist—if the name you wanted wasn’t showing up on its own, you could go online and customize a bottle for five dollars.

Being someone who spent many childhood hours rifling through personalized keychain racks in vain, and as such a sucker for truly broad-scale labeling schemes, your correspondent tried it out. For a while, this was a giddy experience: bottles embellished with everything from “Dinosaur” to “Columbo” danced across the screen, lending their creator a sense of extraordinary power.

But then, while trying to prepare a gag gift for a friend who spends a fair amount of time railing about Coke’s inordinate influence on West African markets, a snag appeared:

A screenshot of a failed Share a Coke attempt, taken on November 24th, 2015. (Image: Share a Coke/Coca-Cola Company)

“Your name is not on our approved list,” the jarring red text warned. “When personalizing Coca-Cola bottles, please have fun, and remember to be respectful, tasteful, and appropriate. Please try again.”

Your correspondent tried again, and then again. It turned out other countries faced a similar fate. A comprehensive test of nations, from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe, revealed that 24 sovereign states do not appear on Coke’s “approved list.” (The existence of such an “approved list,” rather than a disapproved list, is also suspect—random combinations of letters, like “Fslksdgja,” make it through just fine.)

Examination of the blacklisted countries reveals no discernable pattern. America has warred with some (Iraq), but certainly not others (Denmark). Some names may lend themselves inordinately to joking, but it’s unfortunate to think that, say, Kazakhstan’s status as a country worth sharing a Coke with is overshadowed by its association with Borat-quoting teens. Relatedly, while most of the -stans don’t make the cut, you can share a Coke with both Pakistan and Kyrgyzstan. And most of the banned countries have a great relationship with the company itself—while North Korea remains one of the world’s only Coke-free zones, Nigeria just piloted its own special Share a Coke program, featuring smileys.

This was also a surprising move for Coke more generally. After all, this is the same company that poured what was then one of the biggest television commercial budgets of all time into a diverse jingle choir that proclaimed, from a hilltop, “I’d Like To Buy The World A Coke.” As advertorial mastermind Bill Backer recalled in his 1993 memoir, he designed the ad in order to push past the plain old great taste of Coke, and bring out the drink’s potential to provide “a tiny bit of commonality between all peoples.” The ad’s message was so powerful it garnered “a hundred thousand letters” from fans worldwide. A full 44 years after its debut, the message remained potent enough to redeem Don Draper, a man so misanthropic he was actually a self-fictionalized fictional character.

This is also the same company whose seasonal spokesperson’s claim to fame is circumnavigating the world in a sleigh overnight, and which has inscribed a logo in the Chilean desert so enormous that it can be viewed from space. Coke’s Atlanta museum once featured an International Lounge, complete with a country-jumping soda fountain. Indeed, as communications scholar Ted Friedmen wrote in a paper on the museum, Coke has built its brand on a particular sort of “utopian internationalism” in which “the universal consumption of [Coke]… ties people together.”

It all begs the question—why can’t I, your average American consumer, use Coke as it is apparently meant to be used? Why can’t I share a Coke with Russia?

Reaching out to Coke for answers was largely ineffective. In response to a detailed inquiry, they sent along a couple of press releases explaining that this summer’s Share a Coke resurgence added 1,000 new human names to premade bottles, and that the holiday expansion was designed to include various reindeer and elves, not places (although one could argue that “Under the Mistletoe” is a place).

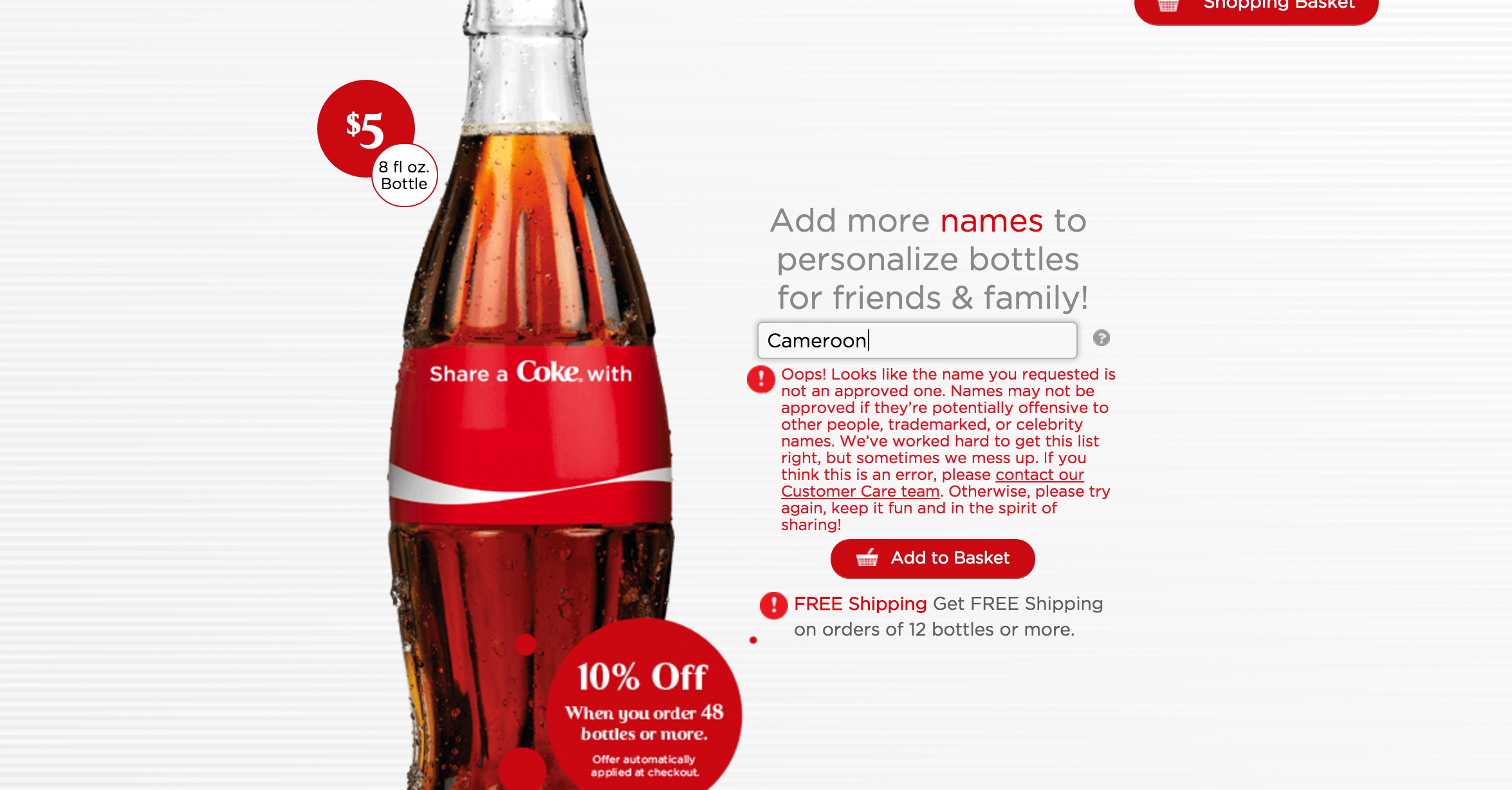

However, at some point over the past month, they did make their disclaimer slightly more friendly. Rather than bluntly reminding site users to “be respectful, tasteful, and appropriate,” the new name-refusal text explains that “names may not be approved if they’re potentially offensive to other people, trademarked, or celebrity names.” “We’ve worked hard to get this list right,” it continues, “but sometimes we mess up.”

A screenshot of a more recent Share a Coke attempt, taken January13th, 2016. (Image: Share a Coke/Coca-Cola Company)

A screenshot of a more recent Share a Coke attempt, taken January13th, 2016. (Image: Share a Coke/Coca-Cola Company)

A new test of the countries in question reveals the blacklist has not budged.

Anyone with further insight into this baffling issue should feel free to grab a nice fizzy beverage with cara@atlasobscura.com.

Update, 1:15 pm: Readers are on the case and theories are rolling in. Here are two from Kyle, who took a look at the front end source code:

1. The bad words / names are stored in what’s called a Bloom filter, which is a probabilistic structure for determining if something is stored or not, but only to a degree of certainty. If crafted correctly, they can hold millions of items in a very small space, but false positives are possible. So maybe these country names represent false positives - but it would be very weird to have so many countries coming up as false positive.

2. Lawyers. Coke is a company with big pockets. I’m not a lawyer but is it possible that these countries represent brands somewhere in the world and are copyrighted? Or maybe those countries has rules about who can use the name of the country? Perhaps it would confuse country of origin labeling?

Jim Newman shares his discoveries:

“You can share a Coke with Michelle Obama, but not Barack Obama.

You can share a Coke with Adele, but not Madonna.

You can share a Coke with Vladimir Putin, but not Kim Jong Un.

You can share a Coke with Heisenberg, but not Walter White.”

Keep ‘em coming!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook