Why the Choctaw People Sent Their Meager Funds to Ireland

An incredible act of generosity sparked a 171-year bond between two peoples.

The Choctaw people had been in Oklahoma less than two decades before news spread about an all-consuming famine in Ireland. Having been ousted from their ancestral lands in Mississippi, they were slowly making a new home for themselves, when, on March 23, 1847, members of the struggling tribe were asked to make a donation for those starving strangers, thousands of miles away.

Seventeen years earlier, the Choctaw had been given a terrible choice. They could retain their autonomy if they were prepared to relocate thousands of miles to Oklahoma, or they could remain in their homes and cede their sovereignty to the United States. The 15,000 people who signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek and left, walked thousands of miles to get to their destination, with as much as a quarter of their people dying en route. Conditions were bleak: In one 1849 account, a Choctaw man described how, since coming to Oklahoma, they had had “our habitations torn down and burned, our fences destroyed, cattle turned into our fields, and we ourselves have been scourged, manacled, fettered, and otherwise personally abused, until by such treatment some of our best men have died.”

Yet amid it all, in a meeting in the stone and timber Agency Building in Skullyville, Oklahoma, they were asked to dig deep for a group of people they had never met. And, incredibly, they did.

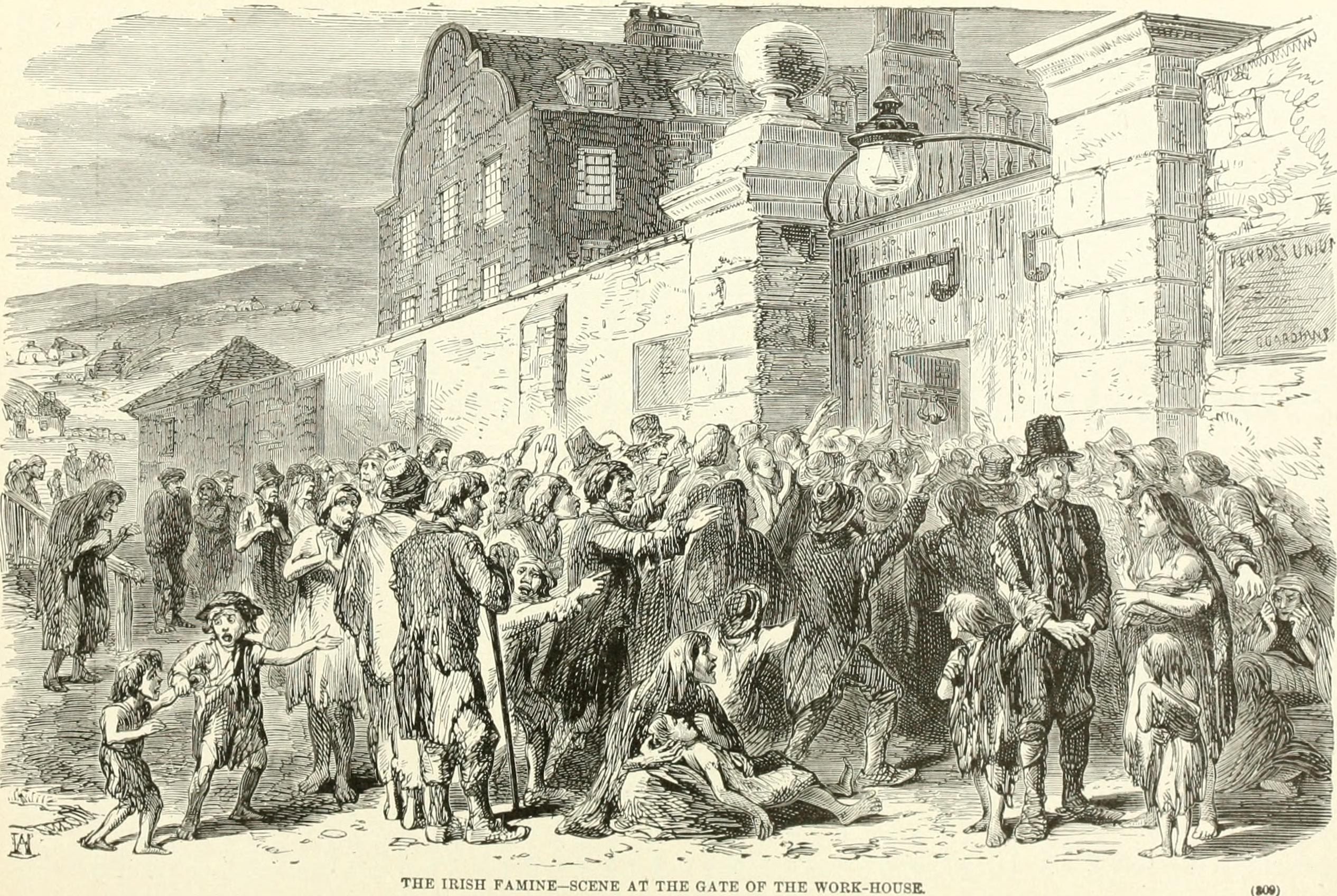

Between 1820 and 1870, around 2.5 million people moved from Ireland to America—more than a third of the U.S. population in 1810. Indeed, the parents of President Andrew Jackson, who had put pressure on the Choctaw people to sign the treaty in 1830, had come from Northern Ireland in 1765. The blight, therefore, received extensive coverage in the American press, as émigrés worried about the friends and family they had left behind. As noted by James M. Farrell, a professor of communications at the University of New Hampshire, in early November 1845, many American papers reported that “a failure of the Irish potato crop”—on which around a third of the country relied—was “now too painfully certain,” with “a famine among the Irish people … apprehended.” Later that year, the Southern Patriot reported, “There is now no part of the country that is not visited by the blight” and “the loss is tremendous.”

The tone of coverage grew more frenzied—the next year, the Ohio Statesman warned Americans of “SIX MILLIONS OF HUMAN BEINGS in Ireland and England, are within eight weeks of STARVATION!” Appeals followed. The general public was asked to give donations of money and ship tickets, and relief committees and charitable societies in churches and synagogues alike sprung up to help to support the starving men and women on the other side of the Atlantic.

It’s impossible to know precisely how much was raised, though it’s likely in the hundreds of thousands, with 118 shipments to Ireland valued at around $550,0000 in 19th-century dollars. Donations came from every corner of American society—even from those least able to give. Children in a pauper orphanage in New York raised $2, while inmates on a prison ship at Woolwich, in London, and at Sing Sing Prison also found ways to send money.

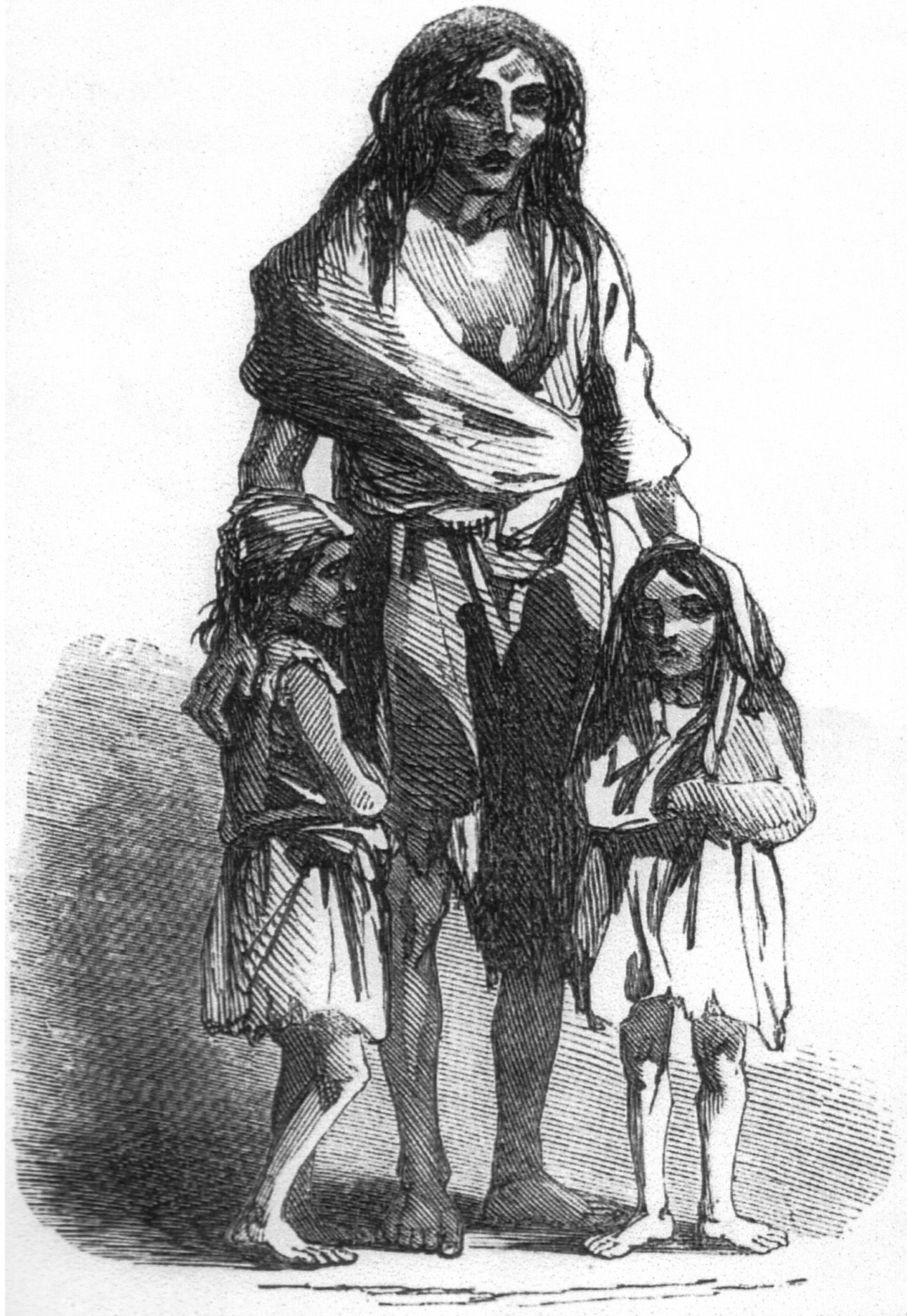

But when Major William Armstrong, an American “Choctaw agent” who represented their interests while implementing U.S. policy, approached them for money in 1847, writes the historian Turtle Bunbury, “he must have experienced mixed emotions.” These were people with very little to give, who had been pressured to cede 11 million acres of their land. Many would still have been grieving the family members they had lost along the Trail of Tears: Though the treaty had been signed 17 years earlier, Choctaw people were still making their way to Oklahoma, arriving at their final destination disheveled, filthy, and exhausted.

“Many would have been destitute or ill,” writes historian Anelise Hanson Shrout in the Journal of the Early Republic. “Most would have experienced enormous financial, emotional, and demographic damage as a result of removal. It is difficult to imagine a people less well-positioned to act philanthropically.” Still, Armstrong took out a circular, produced by the “Memphis committee” for Irish relief, and read it aloud to a crowd of some white settlers—“agents, missionaries, traders”—and a large number of Choctaw Native Americans.

Exactly what happened in that meeting is lost to time. But the assembled group managed to put together $170—well over $5,000 in today’s money. Most of this sum came from the Choctaw people. “It was an amazing gesture,” Judy Allen, then-editor of the Choctaw newspaper Bishinik, told the American-Statesman Capitol on the 150th anniversary of the gift. “By today’s standards, it might be a million dollars.” Bunbury explains it thus: “It is assumed that the Choctaw contributed because they felt immense empathy for the Irish situation, having experienced such similar pain during the Trail of Tears a little over a decade earlier.”

At the time, however, white Americans took the tribe’s generosity not as empathy but as a sign of the success of Christian evangelizing. The 1848 Report of the General Irish Relief Committee notes, on the donation, “The largest part was contributed by the children of the forest, our red brethren of the Choctaw nation. Even those distant men have felt the force of Christian example, and have given their cheerful aid in this good cause, though they are separated from you by many miles of land and an ocean’s breadth.” An editorial in the Arkansas Intelligencer saw it in even simpler terms: “What an agreeable reflection it must give to the Christian and the philanthropist to witness this evidence of civilization and Christian spirit existing among our red neighbours. They are repaying the Christian world a consideration for bringing them out from benighted ignorance and heathen barbarism. Not only by contributing a few dollars, but by affording evidence that the labours of the Christian missionary have not been in vain.”

It would be another five years before the potato famine came to an end. As the Irish people recovered, the Choctaw were drawn into the U.S. Civil War, where they sided with the Confederate States of America, believing that they were promised a state under Indian control if they won. In the century that followed, they continued to struggle with cultural isolation, bullying, underemployment, and an utter lack of political representation. Since the 1970s, however, they have managed to reclaim some of the rights wrested from them in the 19th century, first establishing their own tribal government with a constitution in 1984.

Over the last 170 years, the Irish have remembered this sudden gesture of generosity from distant strangers. Just before St. Patrick’s Day 2018, Taoiseach Leo Varadkar announced an Irish scholarship program for Choctaw youth. As the BBC reported, Varadkar addressed the Choctaw Nation in Oklahoma. “A few years ago, on a visit to Ireland, a representative of the Choctaw Nation called your support for us ‘a sacred memory’,” he said. “It is that and more. It is a sacred bond, which has joined our peoples together for all time. Your act of kindness has never been, and never will be, forgotten in Ireland.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook