Why Are Rats Always the Bad Guys?

And mice always heroes? Experts trace the history of typecasting rodents.

In 1972, the graphic novelist Art Spiegelman was asked to draw something for an animal-themed comic book. As he brainstormed his submission, he recalled in a 2011 interview, he searched for a way to zoomorphize a seminal horror: “Nazis chasing Jews, as they had in my childhood nightmares.”

He dove into all the available archives, looking for inspiration. “As I began to do more detailed and more finely grained research,” he said, “I found how regularly Jews were represented literally as rats… posters of killing the vermin and making them flee were part of the overaching metaphor.” In Nazi propaganda, Jewish people were rats. In Spiegelman’s artwork—which eventually became the enduring Holocaust epic, Maus—they would be mice.

Throughout literary history, when asked to choose a rodent hero, humans have made their preferences clear: mice swing swords, rescue princesses, and save the world. Rats torture dissidents, kidnap cuter animals, and “bite the babies in their cradles.” With some notable exceptions, the mouse’s history and physiology has put him ahead of his larger cousins. And some experts say it’s about time for a change.

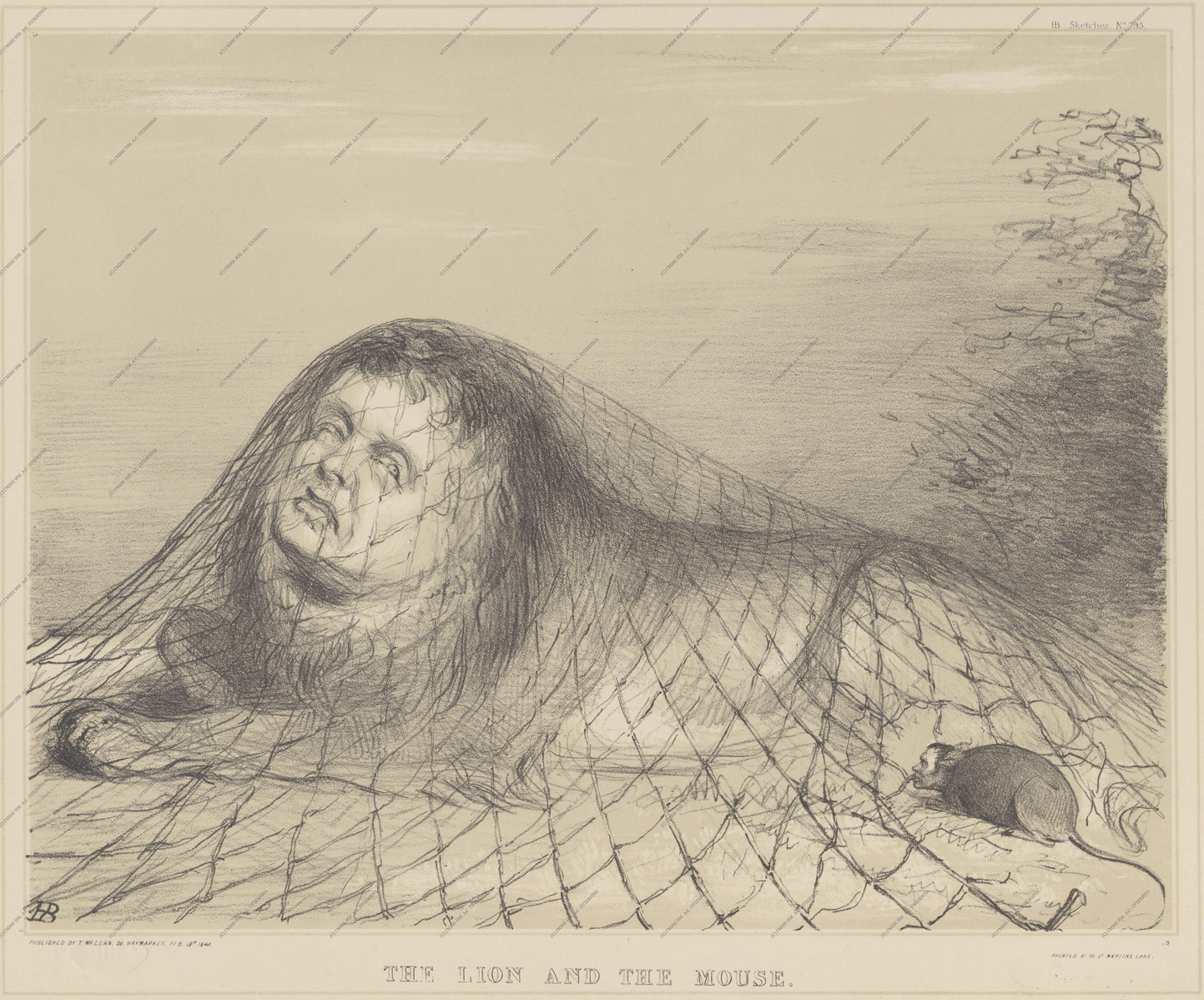

According to Lorna Owen, author of Mouse Muse: The Mouse in Art, mice crept into the popular literary consciousness early on. Aesop, the mysterious fabulist whose work is thought to date back to around 620 B.C., used the lowly mouse to teach all kinds of lessons about human behavior—how to take down stronger opponents, how to befriend important acquaintances, when to avoid petty fights.

This Everymouse proved popular: “Aesop’s fables traveled the world [from Greece] and were reinterpreted by different cultures,” says Owen. Soon, mice were rescuing elephants in India’s Panchatantra, and befriending crows in the Middle East’s Kalīlah wa Dimnah.

Although they didn’t show up much in Aesop, ancient rats alternated between wreaking havoc and teaching life lessons. “From a cultural point of view, the rat is a highly charged figure that can warn and threaten, yet also bring salvation and good fortune,” writes Jonathan Burt in Rat. In the Old Testament, rats are unclean, unfit for touching or eating. But in Ancient Greece and Rome, a group of rats was a portent, signifying joy and plenty. In India, they were considered helpful, and mythological rats would gnaw people or other animals out of tricky situations.

Rats and mice on their own are one thing, but when the two appear together, they invite comparison. “I think often, certainly in the past, these two animals lived right around each other,” says Matthew Combs, a doctoral student at Fordham University who focuses on the brown rat. “One house would have to deal with both problems. You have your mice some nights and your rats some nights… it makes sense to compare them, and to turn them into characters.”

In such a scenario, says Combs, mice are going to win the public opinion poll. Your average mouse eats two or three grams of food per day—a crumb-sized amount—while a rat needs 30 to 50 grams, a human portion. They also brook opposite strategies for getting this food: “I almost think about mice as these little borrowers, sort of benign,” says Combs. “Rats will disassemble the container that you built to keep them out, and rip food apart.” Where a mouse makes a demure mess, perhaps a neat hole in a box of crackers, a rat will leave you with an anarchic one—a ripped-up box with the crackers all gone, and a screw-you smattering of droppings.

If you happen to catch a glimpse of either perpetrator, it won’t help the rat’s cause. “Looking at rats makes people uncomfortable,” says Combs. Where mice have proportionately large ears and heads—both of which, to humans, code for “cute”—rats have small heads, small ears, and large bodies. Combs and Owen agree that the tail is the worst part. “It doesn’t really match with the body you look at,” says Combs. “It almost looks like human skin, but it’s much more gross.” Rats, especially city rats, are also more likely to get scabby and lose their fur. “That beat-up look shows up in stories and characters,” says Combs—like Ratigan, the villain of The Great Mouse Detective, who grows increasingly mangy as his evil plots advance.

When fictional mice evolve, it’s often in the other direction. As Stephen Jay Gould pointed out in “A Biological Homage to Mickey Mouse,” Mickey’s eyes, ears, and snout got larger and more rounded as the Disney brand became more overtly family-friendly.

These physical characteristics affect how we interpret rat and mouse behavior. If you corner a rat, it might leap at you, and take a chunk out of you with its impressive teeth. If you corner a mouse, it will scamper off and hide—objectively cowardly, but courageous in context. “There are little things they do that are actually quite brave when you consider their environment, and how low they are on the food chain,” Owen points out. “They have so many predators, but they still run around.” Small creatures who take risks make great role models for human children, which likely explains everything from C.S. Lewis’s warrior mouse, Reepicheep, to E.B. White’s adventurous Stuart Little.

Of course, these hero-mice require human authors, who can amp up some of their natural characteristics while downplaying others. And rats, too, have attributes that deserve a more positive spin, says Combs. Despite loner literary rats like Templeton of Charlotte’s Web, real rats are very social, he says. “They’ll do lots of play-fighting and grooming and touching, and a lot of affectionate behaviors. You could cast them that way, but often that’s not what we’re given.”

Their intelligence, evidenced by their skill at breaking into food stores and out of traps, is often spun as a sort of sinister cleverness, rather than admirable smarts. In Brian Jacques’s Redwall series, for instance, Methuselah the old mouse is wise and learned, while Cluny the Scourge, an evil rat, is conniving, even insane.

But even the oldest tropes get nibbled through eventually. Combs and Owen see rodent reputations slowly changing, both in quantity and quality. Contemporary mouse storytelling is becoming, to Owens’s trained eye, “a bit repetitive,” while rats are swarming in to fill the void: “In 20th century literature, you have rats more than mice,” she says, citing Orwell’s 1984 and Camus’s The Plague.

As the 21st century scampers on, rat heroes are moving into the spotlight. “Recently, people are a little more accepting of rats as having some good qualities,” says Combs. “There’s movies like Ratatouille. And there’s all this research where they’re using rats as models for human physiology and human medicine.” A recent study shows that, when tickled, rats giggle and jump around. Although scientists could have cast this response as a malevolent cackle, they didn’t—and public response was swift and positive, says Combs. Maybe there’s room for the rat in the hero’s seat after all.

*CORRECTION: This post previously categorized “Notes From Underground” as a 20th century novel—it’s from the 19th century.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook