Found: The Last Traces of Unspoiled Ocean

They’re few and far between.

Humans have a way of leaving fingerprints everywhere, even in places we never physically touch. This is perhaps especially true in the oceans. Currents carry scraps of our trash far, far from our shores. Plastics are regularly lodged in remote reefs, or even drift down to the deepest corners of the Mariana Trench, or wind up along the Antarctic Peninsula. Bags, bottles, lines, and other synthetic materials break down into impossibly small fragments that wander and roam.

But the Earth’s oceans are vast, and a team of researchers recently set out to map what’s left of the unsullied seas.

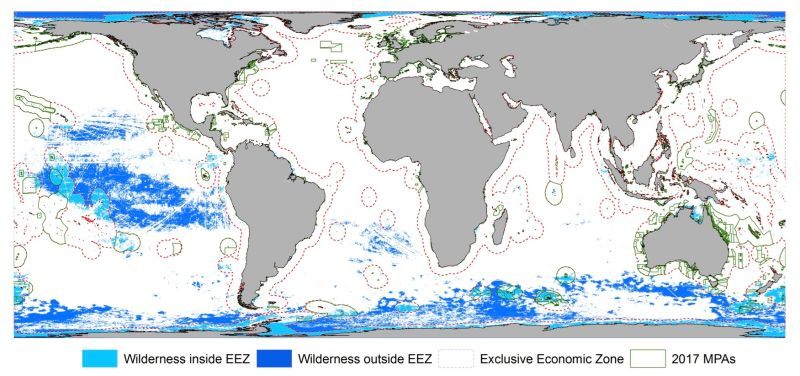

In a recent paper in Current Biology, scientists from the Wildlife Conservation Society, University of Queensland, and other institutions concluded that only 13.2 percent of the world’s waters count as marine wilderness (that is, places relatively unscathed by human influence).

To pinpoint these spots, researchers considered the impact of 15 different human-driven factors—from runoff to fishing—on marine environments, and then identified regions that fall into the bottom 10 percent of impact from these categories. (When they conducted another analysis that included four variables related to climate change, there was basically nothing left.) For the most part, the wildest spaces cluster where one might expect them—in the Arctic and Antarctic, or scattered around the South Pacific. But a few did crop up not too far from land. For instance, some refuges freckle the Gulf of Mexico.

These areas matter, the researchers write, because they’re preciously biodiverse. On average, the wilderness areas had 31 percent greater species richness than more-impacted areas. They also tend to be refuges for species found nowhere else. One example is the kelp-blanketed waters off the rocky Desventuradas Islands, more than 500 miles from the coast of Chile, the only known habitat of Juan Fernández fur seals (Arctocephalus philippii), once thought to be extinct.

But these refuges are hardly safe. Lead author Kendall R. Jones, a doctoral candidate at the University of Queensland, told Earther that many conservation policies focus on places that are already imperiled, rather than buoying and preserving still-vibrant sites like these. “We are arguing that while that [protecting regions in danger] is very important, you need to also balance that by trying to save places that are still wilderness and still acting and functioning as they once were,” Jones said.

The authors found that less than 5 percent of the surviving marine wilderness areas currently fall inside protected areas. As Earther reported, that’s partly due to the fact that many of them are in the vast reaches of ocean outside the jurisdiction of any country—a scenario that the United Nations General Assembly examined last winter, when it kicked off a two-year process for negotiating a treaty that would allow for the creation of protected areas on the high seas.

Meanwhile, Jones and his collaborators call for more attention to marine wilderness, and highlight what would be lost if it vanishes. “The many environmental values of wilderness are very unlikely to be restored,” the researchers write. Once gone, they’re gone.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook