When Plants Attack Unborn Cows

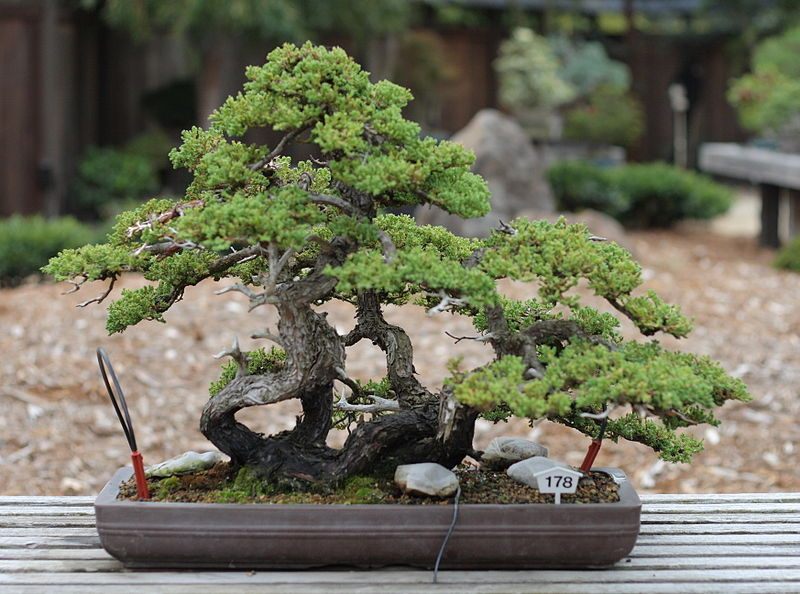

A western juniper tree (Photo: Kurt Thomas Hunt/Wikimedia)

Western juniper trees don’t seem like they’d have it in for cows. They’re shrubby, squat, thick-trunked conifers that grow in the Pacific Northwest, not matadors bent on revenge. And they don’t have meat cleavers, just tiny, scale-like leaves that are layered on thick at the fractal ends of branches. But maybe juniper trees are a little bit mad that cows eat those branches. Maybe that’s why juniper enacts revenge.

Because when pregnant cows chow down on western juniper, they often lose the fetus they’re carrying.

Living creatures develop defenses to keep them alive, and for many plants, those defenses come in the form of chemical compounds that are distasteful or dangerous to animals. Often, those compounds serve as warnings. A bitter taste might make the animal stop eating; an emetic effect may ensure it won’t happen again. But a few plants have a special and deadly skill: they stop their predators before the predators are even born. When eaten, these plants cause certain mammals to abort.

And, as with many strategies meant to keep plants alive, human have managed to turn this talent to their own ends.

Juniper berries (Photo: Dcrjsr/Wikimedia)

Western juniper didn’t ask to be anywhere near cows or their reproductive systems. It was just minding its own business, trying to take over as much of the world as possible, as all species are wont to do. Starting more than a century ago, the trees began systematically taking over eastern Oregon: according to a Forest Service report, juniper forest in the state covered 1.5 million acres in the 1930s and 6.5 million acres by the mid-2000s. Now it’s up to 9 million.

Humans have fought back, mostly by cutting down large number of juniper trees. That left them with a larger supply of dead juniper trees, and sometimes, they’d just leave them in a big pile. Sometimes, they lay them on stream beds, to help with erosions.

The problem started when hungry cows came across these sort of installations. “They’d eat quite a bit of bark and needles, and they started having abortions within a few days,” says Kevin Welch, a research toxologist at the USDA’s Poisonous Plant Research Lab. “Some of these ranchers, 10-15 percent of their cows were having these abortions.”

Ranchers already knew that a different conifer, the Ponderosa pine, posed a danger to their cows. In the 1920s, cattle farmers had started wondering if these towering evergreens were causing abortions. For years, that gut feeling was dismissed. There were so many more obvious causes of abortions in herd animals, mostly infectious agents – like Toxoplasma gondii, the parasite that cats often carry, or Salmonella, which can cause sheep or goats to lose pregnancies.

But the ranchers were right. In 1952, the Journal of Rangeland Management reported on an experiment that involved feeding cows ponderosa pine needles and documenting premature births. The needles, research found, could cause cows to lose their fetuses. Sometime, the abortion didn’t happen until several weeks after the cow’s pine-flavored meal.

Essentially, the pine needles cause the cows to go into labor early; if it was far enough along, the calf might even be born, but weak and unlikely to survive much past birth. And there isn’t much that ranchers can do about it. “The only way to prevent pine needle abortion is to keep cows away from pine trees and pine needles,” one ranchers’ management guide warns.

Ponderosa pine needles pose a threat only to cows. But there are a few plants that cause abortions in other herd animals, too, including annual ryegrass, broomweed, wild pea, skunk cabbage, and locoweed (which also makes animals act crazy). “Locoweed will cause abortion in basically any animal species,” says Welch. But some plants limit their impacts to certain types of animals: Skunkweed, for instance, will cause a problem for any ruminant animal, but not an animals with a simple stomach.

Western juniper, though, wasn’t a known threat. Like pine needles, juniper branches aren’t a normal part of cows’ diet, though cows will munch on them if there’s nothing better to eat. And sometimes, in the winter, there might not be. But Welch and his colleagues decided to look into this new hunch. First, they found that western juniper contained isocupressic acid, the same compound that was so dangerous to cows in pine needles.

Then, they started monitoring six pregnant heifers, and when the cows reached day 250 of their pregnancies, dosing them daily with ground up juniper bark. Within five days, two of the cows had aborted.

It’s not just ponderosa pine and juniper that contain isocupressic acid, either. USDA researchers have analyzed 30 to 40 trees that have this compound, Welch says. If a cow eats enough of these plants in the last trimester of a pregnancy, there’s a chance she will abort. And with the next pregnancy, she might make the same mistake. With these kind of compounds, especially with pine needles and juniper, there’s no adverse effect on the mother, says Welch. And so they never learn not to eat them.

Humans have been using juniper for their own purposes for millennia (Photo: Sage Ross/Wikimedia)

In Oregon, juniper is now The Enemy. “There isn’t a natural resource professional in Baker County who doesn’t want to get juniper out,” the state Department of Fish and Wildlife wrote in a newsletter recently. Ranchers willingly go after it with chainsaws. The Bureau of Land Management has tried to systematically thin it. There’s even an alliance among different factions of humans to fight back against it.

This is a bad turn in humankind’s relationship with juniper trees, which likely goes back millennia. Western juniper is just one of a dozen species of juniper; they live all across the northern hemisphere, in Asia, Russia, Europe, and North America. One type of juniper skirts down the eastern coast of Africa. They live among limestone and sandstone, down at sea level and up high on mountains. Their cones are fleshy, blue-colored, and often called “berries,” even if, technically, they’re an entirely different mechanism for reproduction.

At times, humans have enjoyed the presence of juniper. They make good wood and beautiful bonsai trees; in one Grimm fairy tale, a murdered boy is buried beneath a juniper tree, where he’s transformed into a bird and exacts revenge on his killer. Juniper berries, most famously, are the key ingredient to gin.

And, according to the Encyclopedia of Folk Medicine, juniper is also “one of the few plants that we know was almost universally used for abortion.”

Long before modern contraception, women across the world sought out ways to prevent pregnancies or end existing ones. And just as they can cause herd animals to terminate pregnancies, a whole slew of plants—clover, willows, alfafa, fennel, pennyroyal—can cause humans to abort, too. (“Morning” sickness may be an adaptive response to avoiding such threats.) Some of these birth control methods were administered orally; some were poultices that had to be applied vaginally.

They weren’t always as effective as modern abortifacients, but modern research has shown that at least some of these plants can disrupt human reproductive cycles. And among them, juniper had a reputation for effectiveness: in some places, it was called “bastard killer.”

The best defense that people have to protect ourselves and our cows is to keep away from juniper. That’s what ranchers have tried to do, and to some extent, it’s worked. But these plants do have a secret power over mammals like us. They can’t take a hacksaw to humans, as we do to them, but they will keep us from reproducing, given the opportunity.

After all, there’s only room for so many cows, people and juniper trees in this world.

A felled western juniper (Photo: NCRS Oregon)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook