No Matter What, Do Not Touch the Space Junk

You almost certainly won’t encounter any pieces of the falling Chinese space station, but if you do—keep your distance.

Stan Thornton had just three days to get from his town of Esperance, Australia, to San Francisco to claim his prize. To hustle things along, a radio station in Perth paid his airfare, and U.S. officials expedited his visa. When he boarded the plane in July 1979, the 17-year-old packed a fresh outfit, a toothbrush, and some charred space debris.

NASA’s Skylab had reentered the atmosphere a few days prior. The American space agency had intended to steer the 100-ton orbital station toward the Indian Ocean, but miscalculated. (Given the number of variables affecting the descent of space debris—from drag to solar flares—the margin of error is wide.) Instead, Skylab came down over the southwest corner of Australia. The sky lit up orange and blue and there was a series of booms that sounded, to people on the ground, like helicopter blades. Debris rained down like “a massive hailstorm” that pelted Thornton’s backyard and tin roof.

When metal rain stopped falling, plenty of people went outside to pick through the debris. One community took the doors off their town hall to squeeze a chunk of the space station inside. (“Very good for the tourist industry,” the mayor said.) Thornton brought some black nuggets he retrieved to California, where he claimed a $10,000 bounty offered by the San Francisco Examiner, for being the first to bring pieces of the station to the newspaper’s office. He easily made the 72-hour deadline with 14 hours and 38 minutes to spare.

At the time, NASA officials told the Associated Press that it was safe to pick up pieces of Skylab—they weren’t radioactive, and they’d likely have cooled by the time they reached the ground. But as the Chinese space station Tiangong-1 nears the end of its decaying orbit and approaches the atmosphere this weekend, it’s important to know that that a space junk treasure hunt is not a good idea—however fun it may sound.

To be clear, it’s unlikely that Tiangong-1 will hit land, and even less likely that it will come down in a populated area. True, its descent is uncontrolled, and it’s nearly impossible to forecast the precise time and location of reentry. But it comes down to numbers, says Lisa Ruth Rand, a postdoctoral fellow and space junk scholar at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Given that nearly three-quarters of the planet is ocean, the space station is much more likely to crash into water than someone’s yard.

In the improbable event that it does plummet near you, observe it from afar. Anyone who spots a piece “should absolutely not approach it,” Rand says. “One hundred percent, keep distance.”

Any object steaming on the ground could be dangerous, and Tiangong-1 could be particularly hazardous because it may hold hydrazine fuel, says Marco Langbroek, an amateur astronomer who is carefully tracking the space station’s position. There could be any number of other dangerous compounds in or on the space station, too—what, specifically, isn’t known because the Chinese space program “hasn’t told anyone what it’s actually made of,” says J.D. Harrington, a public affairs officer at NASA.

If there is hydrazine on board, it could be dangerous in water, too—but there’s little data about its reactivity, as Michael Byers, an Arctic expert at the University of British Columbia, explained to The Star in 2016, when a Russian rocket stage thought to be carrying hydrazine was set to fall into Baffin Bay. Up close, remnants of this corrosive propellant could “do some very nasty things to your skin,” Langbroek adds—and if you inhale it, “that basically kills you.” If you do spot debris, Harrington says, call local authorities.

Salvaging space debris can also run people afoul of the law, as some souvenir hunters learned when they gathered fragments of the shuttle Columbia in 2003, after it tragically broke apart during reentry. In Texas, some residents beat authorities to the wreckage—the debris field spanned hundreds of square miles—and put pieces of alleged debris up for sale on eBay. “People should not be collecting that at all,” NASA spokesperson Bruce Buckingham told the Associated Press at the time. These incidents also raised ethical questions, because all seven crew members lost their lives in the disaster. And the law is clear: Objects in space are the property of the state or company that put them up there, and that holds true back on Earth as well. At least two people in Texas were indicted in 2003 for collecting wreckage from Columbia, and faced prison time and fines up to $250,000. Skylab was a different scenario, because NASA wasn’t interested in retrieving the material. People were allowed to keep what they found, unless they wanted to file an insurance claim for injury or property damage, for which the U.S. government would be responsible. No one did.

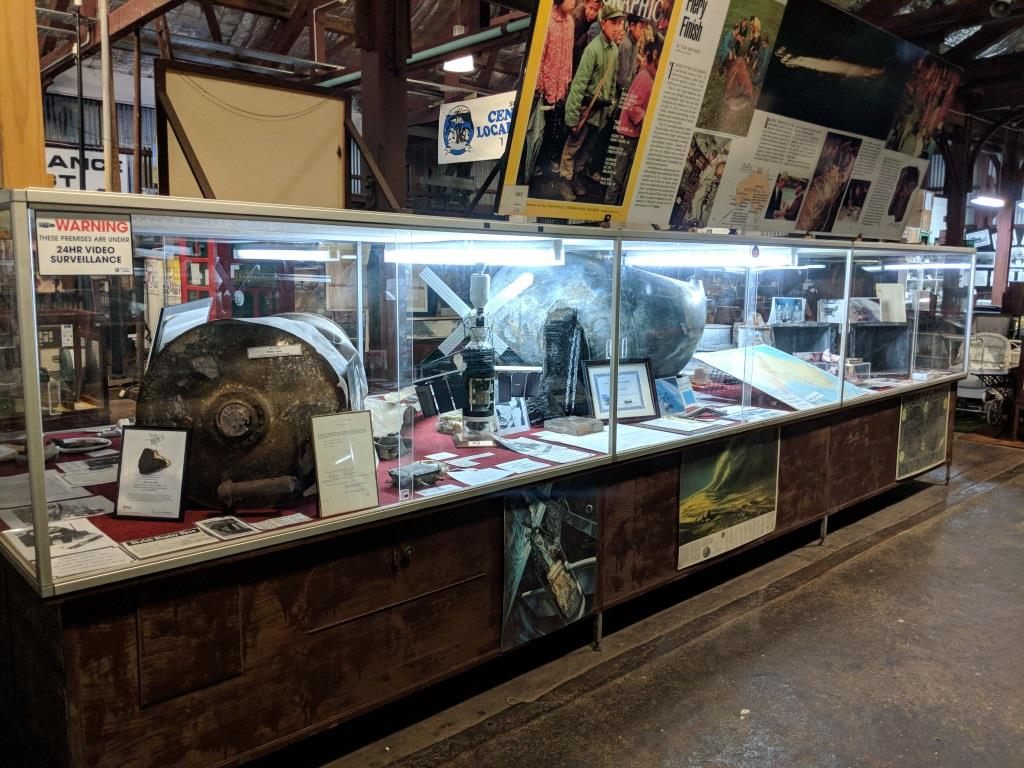

As Tiangong-1 reenters the atmosphere, your best bet is to watch it on your computer (or look up, if you’re very lucky), and stay far from any debris if it comes down near you. If you truly must see some space junk in person, you can always plan a trip to see Skylab’s remains, some of which are on display near where Thornton and others found them, on Australia’s southwest coast. “Esperance Museum is proud to have items of Skylab as one of our displays,” says Lynda Horn, the shire’s cultural officer. “We always receive comments from visitors saying that they have come to see what we have in the museum as well as more specific comments that they are here to see Skylab.” It’s quite unlikely that Tiangong-1 will end up in a vitrine. But if you do catch a glimpse overhead, enjoy the show.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook