The Old Agricultural Tradition Reuniting Modern Families

In rural France, filling homes with pate and sausage was once a matter of survival.

The sky was still dark when we arrived at the Bibal family’s ancestral home, a large farm house surrounded by pasture in Sainte-Gemme, France. The day began—as it always does during their annual February visits—with a large family breakfast. We had visited the pig the evening before, when she was delivered by a local farmer. She slept on a thick bed of hay in a pen formerly used by the family patriarch, Fernand Bibal, to house animals. The large country house was equipped with all the accoutrements of subsistence farming: pens for livestock, chicken coops, and a granary. Normally, all that lies empty, except for once a year, when the large family convenes to keep the tradition of the tue-cochon alive.

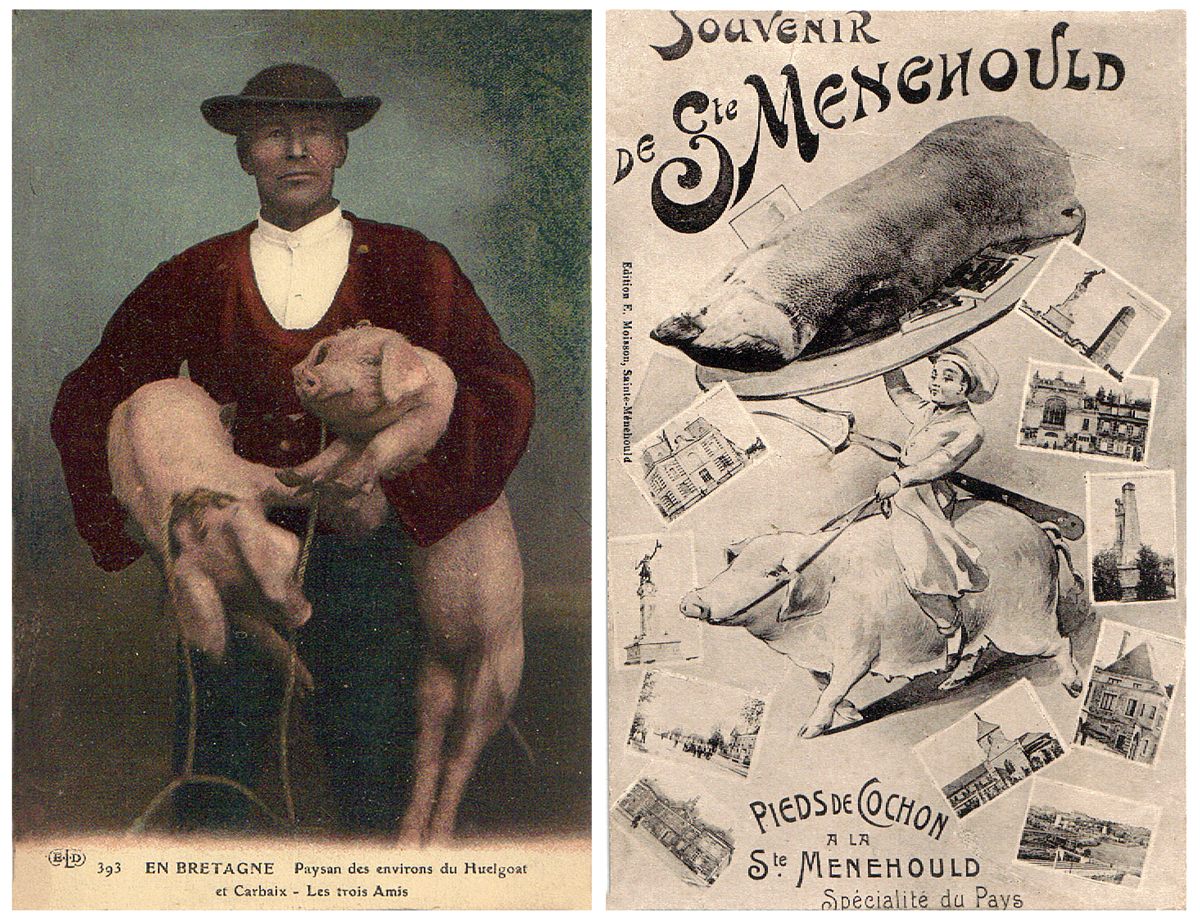

The wintertime custom, which literally translates to “pig slaughter,” was once a matter of survival. When food was scarce and snow covered fields and gardens, families needed preserved foods. In France, pork provided the necessary base for rural families’ meals, and the process of salting and drying pork remained crucial for survival until only a few generations ago. Pork achieved such high regard that pigs were featured in famous French Belle Epoque postcards, and quintessential foods such as confit, pâté, boudin, and all manner of sausages can be traced to this need to preserve meat before the advent of refrigeration.

The Bibals no longer live in the country. Like many families, they left the fields for office jobs and city life: Frédéric practices law, Cécile is a physician, and they live just outside Paris with their four children, Noé, Joseph, Madeleine, and Suzanne. But each year, the Bibals’ extended family convenes to continue the tue-cochon tradition.

“We [still] do it because in our family, we have always done it,” says Marc Bibal, Frédéric’s brother. “In our region, everyone did it. There is not a family that has not participated in the tue-cochon.”

Families like the Bibals have another motivation for keeping up the tradition. While many French regions have historically participated in the tue-cochon, their recipes, which families hand down, are distinguished by local tastes and how preservation requirements differ by climate. “The sausage we love can’t be found easily. Or if we find it, it’s now too expensive to buy in stores,” says Marc. “We’ve been eating it this way for so long, we want to keep eating it.”

What sets the Bibal family apart is that their great-grandfather, Fernand, was himself a Saigneur, a respected post occupied by one who holds the knowledge of how to properly kill and butcher the pig. Fernand’s son, Guy, described his father in a book he wrote on his life in the countryside:

I can still remember Papa leaving early in the morning on his bicycle, his canvas bag full of tools, coming home late in the evening with just enough time to take care of the cows. How busy were his days then.

What was once a hard, long day of life-sustaining labor is now more relaxed, happening over two days and punctuated by large meals and conversation. While a Saigneur hired by the Bibals quickly slaughtered, cleaned, and prepared the pig for butchering, the children ran around in brightly-colored galoshes. Next, the family boiled water over an open fire and placed portions of the meat in a large iron cauldron to be slow-cooked. The eldest sibling, Noé, helped his father stir the meat for hours, ensuring it did not stick to the cauldron. Nine-year-old Suzanne spent most of her time in the kitchen preparing the pâté tins with her grandmother, but eventually ventured out to the garage to help prepare the meat for the saucisse, mixing just the right amount of salt, pepper, and fat in her tiny hands. A tue-cochon uses almost every part of the pig.

At end of two very long days, the family and a few neighbors convened for dinner and “judged” the finished products. As they passed wine, inevitably, they shared stories of previous tue-cochons and compared the meat to previous years’ efforts. After the meal, a handful of family members played a card game called le bourro and drank wine and tea until it was time to say goodnight.

When the Bibals arrived at the house, the first order of business was to set up the wifi. But soon enough, this light, convivial atmosphere prevailed. The kids took long walks, venturing into nearby fields and hopping onto neighbors’ hay bales. Back in the house, Noé spent hours rummaging through drawers and bringing out old photo albums, asking his parents who was who. All was stripped away except the communion of family, and a reverence for the past pervaded even the youngest.

Since the passing of Fernand in 2010, the family has hired a local man, Gilbert Moulin, to perform the tue-cochon. He talks fast and laughs often; his quick nature belies his age and ill health. We sat in his kitchen, where family photos line a wooden curio cabinet.

“I was born right here. Right here in this house,” Gilbert Moulin says.

Gilbert learned to be a Saigneur at the age of 17, from a local man who invited him one day to help perform a tue-cochon. During the busiest times, Gilbert performed 90 between November and February. Now he does around 12, due to his age and the drop in interest from other villagers.

The practice started to decline in the 1990s, when many farmers switched to wheat and stopped raising livestock. Eventually, many children moved away and pursued jobs outside of agriculture. Fernand’s son Guy was encouraged by a teacher to go to school in Paris, where he studied engineering. He and his son, Frédéric, both still live in Bry Sur Marne, just outside the capital. This process has led shops and schools to shut their doors in what has been called the “desertification of rural France.” In some places, baguette vending machines have replaced long-revered bakeries. Local traditions are in danger of disappearing.

Marc Bibal, a veterinarian now living in a small town in the Savoie region, who is Fernand’s grandson, wants him and his son to learn how to slaughter a pig properly. “It’s a great responsibility to be the Saigneur,” he says. “If you mess up, it’s a huge deal.” He doesn’t intend to become a Saigneur himself, but hopes to keep the tradition alive for future generations of Bibals. Luckily, Gilbert, the elderly Saigneur of the village, recently took on a teenage apprentice.

The tue-cochon and the coming together of relatives brings cohesion and joy to the Bibal clan. The meat they prepare is a link to the past and a physical result of time spent together. Over the spring, the pâté tins will disappear from the pantry, and the sausages will be eaten over many dinners. Next winter, though, everyone will convene again to start the process anew.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook