The Holy Grail of Video Game History Is Probably an Office Memo

The Video Game History Foundation is trying to preserve the stories behind the fun.

Seeking the holy grail of video game history might bring to mind the internet-shattering discovery of some long-lost NES classic. But for the Video Game History Foundation (VGHF), a young organization working to collect and preserve the disappearing ephemera of gaming history, the grail is probably something closer to some scribbled notes or old meeting minutes.

The VGHF, a registered nonprofit, was founded in February 2017 by video game archivist and historian Frank Cifaldi. “As an individual, I’ve been preserving video game history since 1998,” says Cifaldi. “Going back to the days when I was dumping NES cartridge ROMs on the internet.” (That is, he was pulling the game code off the cartridges, so they could be played using computer-based emulators.) Cifaldi started the Foundation as a way to locate and preserve the ever-fading historical legacy of a multi-billion-dollar industry, and to encourage more in-depth and probing discussion on the subject.

Today, the art involved in video game development is more evident than ever, but as many have noted, this was not always the case. “For most of video game history, there was no point in holding on to that source code, because you’re never going to port it or anything to another console. You did the game, it’s out, and you move on to the next one,” says Cifaldi. In addition to the source code for the games themselves, the behind-the-scenes materials that tell the story of a given game’s creation and release are even harder to come by. While there is some incentive and means for fans and others to copy and pass on a game itself (namely fun, via the aforementioned ROMs), those more ephemeral materials are usually only ever found in the possession of people who worked on the original games. For whatever reason, they rarely bothered to hold onto items from production—or the companies that made them went out of business or were acquired by other companies. As Cifaldi points out, time is running out for such discoveries. “We’re hitting the point where this industry is old enough that people are starting to pass. It’s time to take this stuff seriously.”

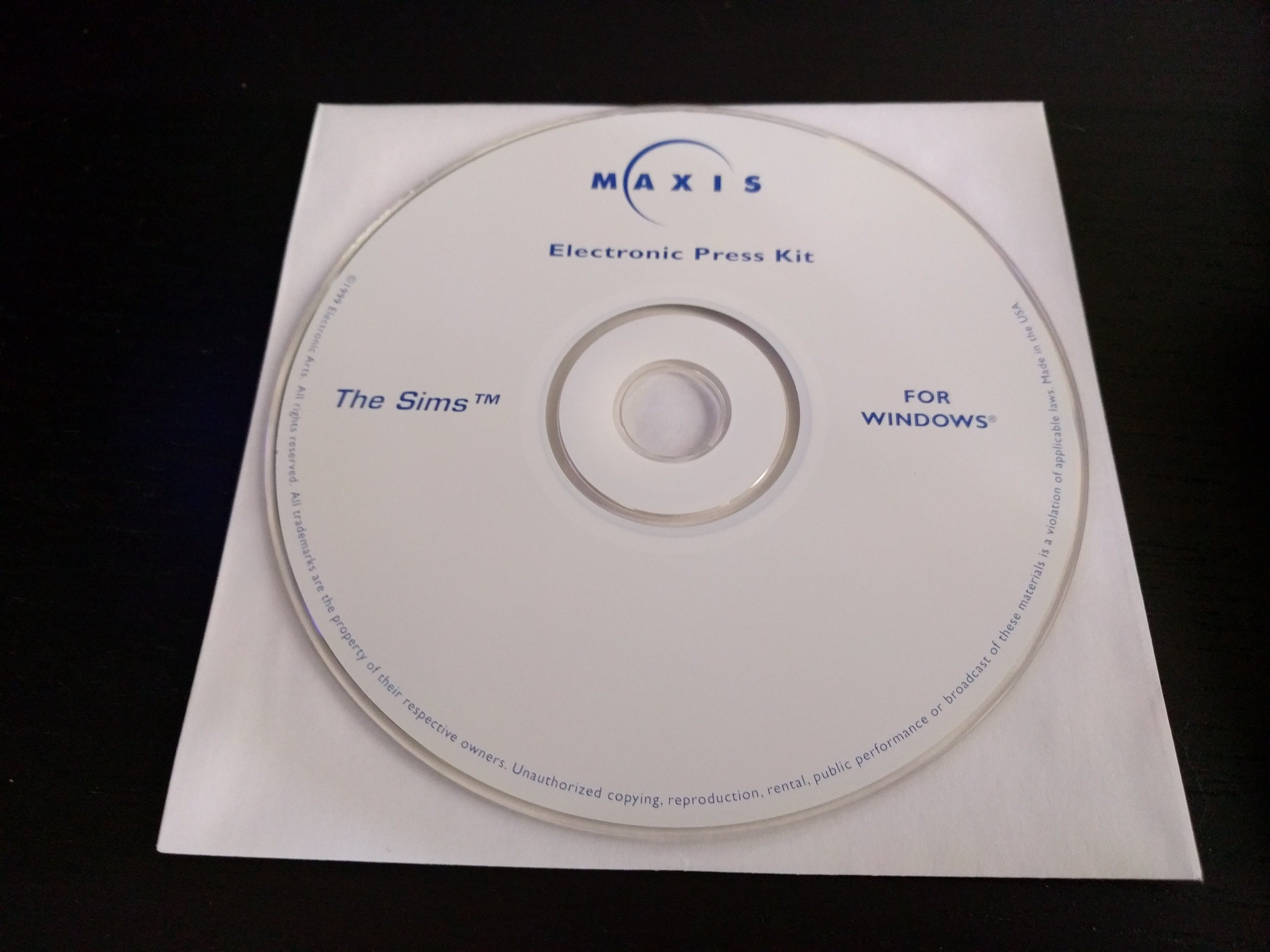

VGHF does its fair share of preserving code and the technology for playing games—the primary source materials of video game life. “In general, the holy grail of video game preservation is source code,” Cifaldi says. “That’s what actually builds games.” But there are many people who do this, and do a good job of it, from independent ROM collectors to the handful of museums across the country that collect video games or the thousands of titles available on the Internet Archive. But unlike these other preservation efforts, VGHF is seeking the materials and information surrounding the games—Cifaldi wants to preserve context, to better understand games as historical artifacts. “You can play Super Mario Bros. and enjoy it for what it is, but if you understand the time and place, and how it was actually kind of new that there was a blue sky, and that the screen scrolled, you understand why it was so impactful, and you can appreciate it in a different way,” says Cifaldi.

Cifaldi often compares the struggles of video game scholars to those of film scholars. “Film scholars have access to studio correspondence between the director and the production company, they have things like shooting scripts for the movie, etc.,” he says. The video game industry just hasn’t preserved similar materials. These seemingly mundane assets could help fill in the surprisingly large gaps in gaming’s historical record—simple things such as the release dates of games, which weren’t really publicly announced until the 1990s, with a few exceptions. “Sonic 2 had a whole marketing campaign around ‘Sonic Tuesday.’ I’ll never forget it. November 24th, 1992,” says Cifaldi. Most simply appeared in stores, sold or didn’t sell, and were forgotten.

The items the foundation is searching for could range from old advertisements and game reviews to scribbled development notes and internal memos, and even just old pictures of people working on games. “We don’t know what game studios looked like inside for the most part, or what the development environment would have looked like,” says Cifaldi.

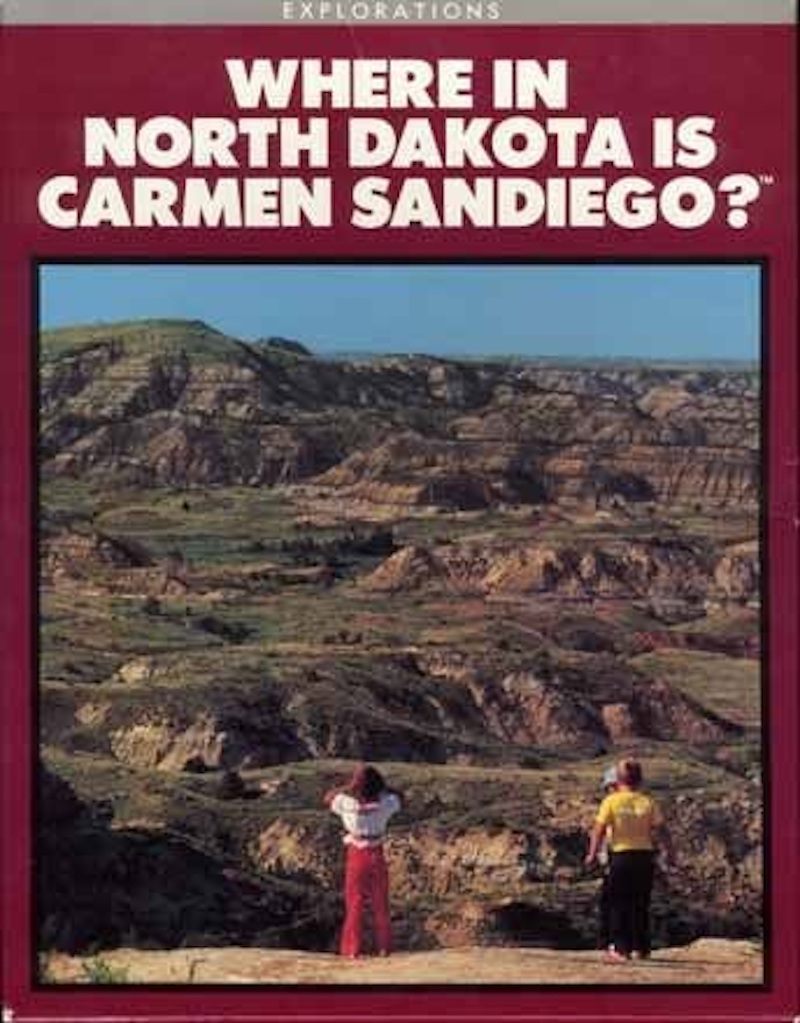

One example of a game that the foundation was able to save from the memory hole of history was the odd Carmen Sandiego franchise extension, Where in North Dakota Is Carmen Sandiego? Like a TV pilot that never went to series, the game was developed in 1989 by Broderbund Software and a group of North Dakota teachers in an attempt to create a region-specific version of the popular Carmen Sandiego educational games. Unsurprisingly to everyone outside of North Dakota, it never took off. “The game was maybe sold at retail? But we have no record of that happening,” says Cifaldi. “All we have is a complementary copy that was sent to the teachers.”

But the game was completed, and members of the VGHF actually travelled to North Dakota to collect everything they could about it from teachers who still had related materials. They found handwritten notes from the teachers, correspondence between them and Broderbund, worksheets that would have been given to students playing the game, and early and finished builds of the game and its manuals. All of this was insight into its development and evolution. They even found photos of the teachers working on the game.

VGHF presented a playable version of Where in North Dakota Is Carmen Sandiego?, along with a clue guide, at the 2017 Game Developer’s Conference. No one who tried it was able to catch any of the game’s crooks. Still, a game that was little more than a barely remembered oddity now has a story of its own.

Not yet through its first year, VGHF is working on digitizing its growing collection and expanding its influence. Cifaldi and his colleagues recently launched a writing fund to encourage scholars to create thought-provoking writing on the history of gaming. As it evolves, Cifaldi would like to see it continue to do the work that foundations do—raising money to support projects that align with its mission.

In the meantime, Cifaldi will keep preserving gaming’s fading history the old fashioned way: “A lot of it is just tracking down and talking to people who were in the industry and encouraging them to understand that their contributions were important, or that some of the material they have is important.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook