In the Victorian Era, Valentine’s Day Was a Celebration of Same-Sex Romance

Such “smashes” were encouraged when women were considered “passionless.”

It was February 1888 and Vassar College freshman May Copeland could hardly wait for Valentine’s Day to arrive. Ever since matriculating at the single-sex institution in New York the previous autumn, May had been infatuated with a senior named Genie. Now, she finally had just the right opportunity to express her admiration for the older student. “The girls have a custom of sending Valentines to the Seniors every year,” she explained in a letter to her mother, “and instead of just sending cards, they write sentimental and funny poetry to them, and it is great fun.” Inspired by this campus tradition, May impressed herself with what she called her “poetical genius,” penning a “very killing” poem and painting violets on an anonymous tribute to her beloved.

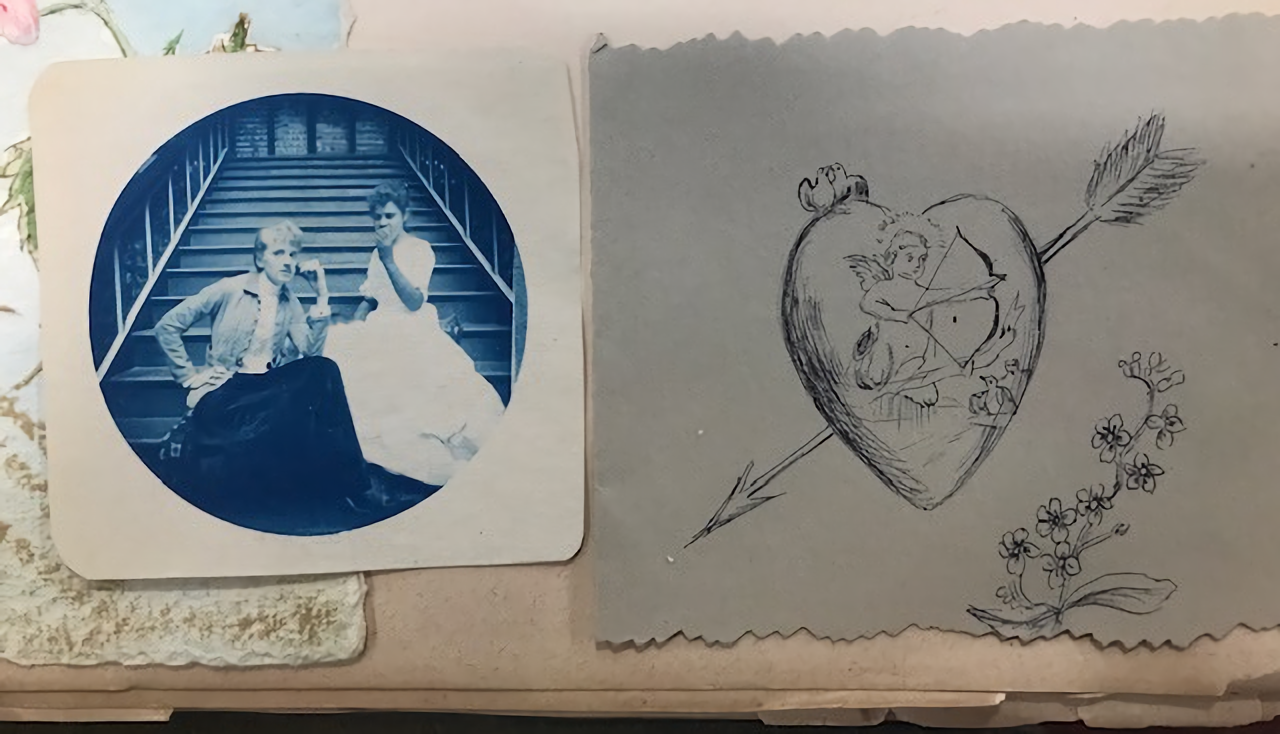

May, like many of her peers, engaged in a series of same-sex romances — known as “smashes” or “crushes” — during her time at Vassar. Such relationships, ranging from one-sided adoration to mutual devotion, were common at women’s colleges in Victorian America. Between the Civil War and World War I, it was de rigueur for “freshies” to become besotted with seniors and for older students to “escort” younger students to social events. While students routinely showered their sweethearts with tokens of their affection, including candy and flowers, Valentine’s Day was the ultimate salute to same-sex romance.

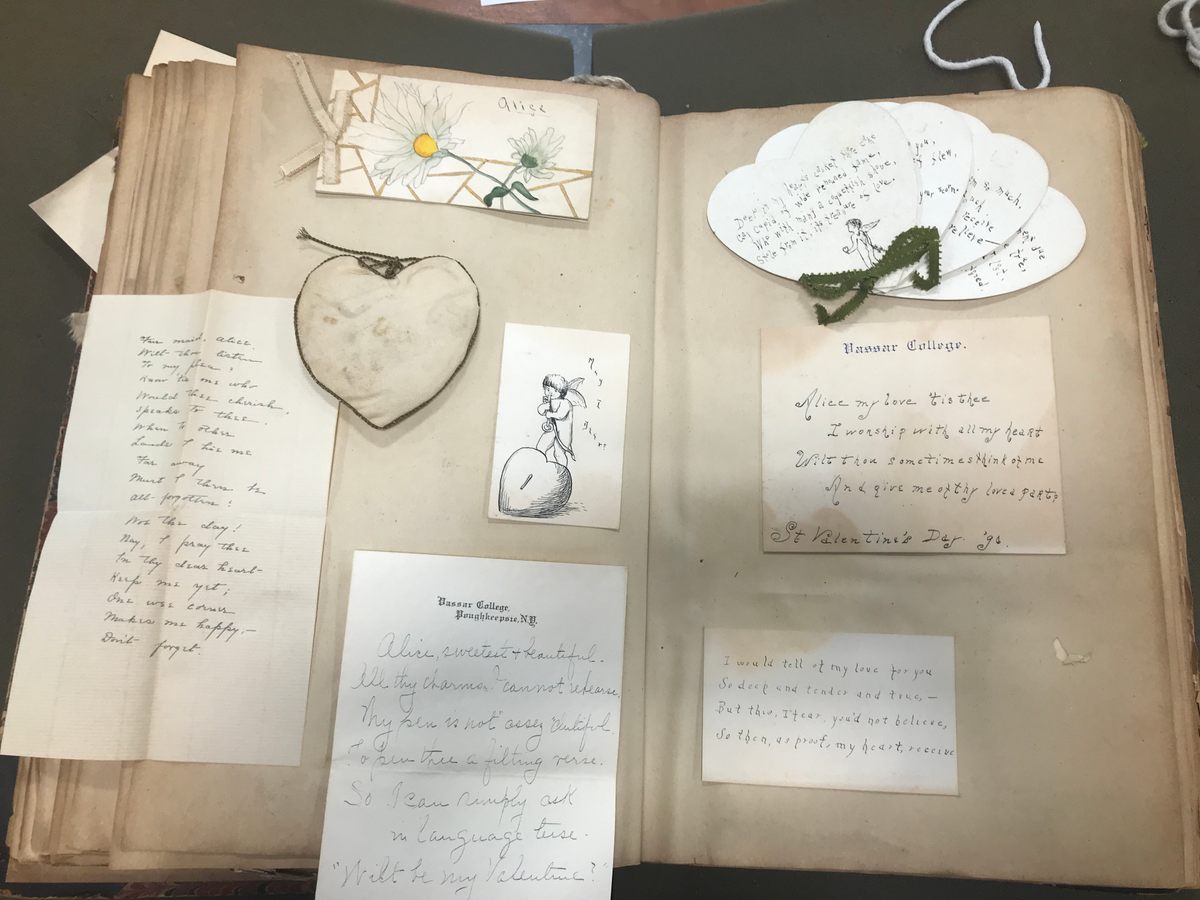

In the Victorian era, Valentine’s Day was an annual ritual celebrating women’s relationships. At Vassar College, students designed and produced handmade cards, drawing and painting floral tributes and composing original verses dedicated to the lucky recipients, who carefully preserved such offerings by pasting them into the pages of their scrapbooks. Such practices highlighted Victorian Americans’ positive attitudes toward female friendship and the widespread acceptance of same-sex relationships in nineteenth-century America. But in the early twentieth century, responding to new fears about lesbianism, college authorities launched a concerted campaign to “crush the crush,” as historian Wendy L. Rouse phrases it. Concerns about “the lesbian menace” constrained campus celebrations of same-sex romance for more than a century.

Female friendships flourished in turn-of-the-century America. At a time when most Americans regarded women as “passionless,” college authorities encouraged close relationships among students. Vassar administrators assigned same-sex exercise partners, hosted single-sex dances, and assigned students to shared suites.

Students enthusiastically embraced the opportunity to forge friendships and pursue romantic relationships. May Copeland especially enjoyed the dances held every evening on the college campus. Her first year at Vassar, she confided to her sister: “It is lots of fun though there is never a man to dance with.” By the time she was a junior, May eagerly anticipated single-sex dances and enthusiastically joined her classmates in dressing up “to fascinate the Freshmen.” At a rare mixed-gender event, she scorned the college men in attendance as “inane idiotic looking fellows” and instead lavished attention on her latest crush: “Jean Waters looked perfectly lovely as usual,” she gushed in a letter to her mother. “She wore a black lace low necked gown, and O, her hair was so lovely.”

Female friendship and same-sex romance alike had their day on Valentine’s Day. After devoting days to planning and producing elaborate expressions of affection, on the day itself, Vassar students placed baskets, boxes, and bags at their doors to receive cards from others while they ventured forth to deliver their own tributes. Between classes, they delighted in reading their cards aloud, evaluating their artistic and poetic merits, and speculating on the identity of the anonymous authors.

In the evening, Vassarians decorated the dining hall tables with gilt hearts, papier-mache cupids, and fresh flowers. They pinned paper arrows to their clothing to suggest they were pierced through the heart. Finally, they carefully counted their cards and honored the senior who received the most valentines as the “Queen of Hearts.”

Vassar students saw women’s relationships as the quintessential expression of Victorian values, thoroughly imbued with sentimentality yet entirely devoid of sex. One Vassar Valentine’s Day poem epitomized the intensity of romantic feelings and the ideal of female purity that characterized the Victorian era: “I love thee, tho’ I know thee not, / For fair thou art and pure, / And ever happy would be my lot, / If I could thee but lure.”

Despite the cultural ideal of female passionlessness, it seems likely that some same-sex relationships in Victorian America were sexual in nature. While evidence of sexual activity is scant, examples of long-term “lesbian-like” relationships abound. As Lillian Faderman shows in her study of women educators and activists, and as Wendy Rouse demonstrates in her recent book on queer suffragists, many women in turn-of-the-century America formed domestic partnerships, which Victorians referred to as “Boston marriages.”

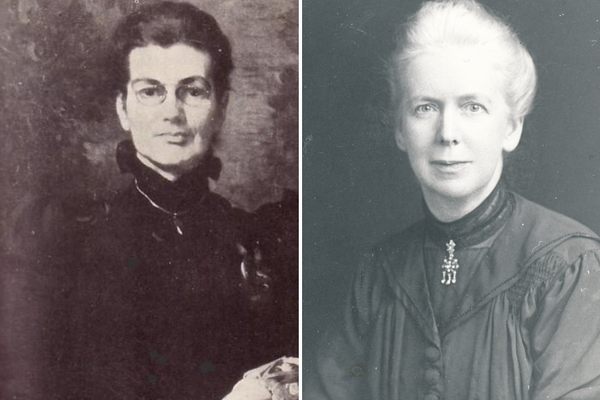

The single-sex college campus — which the late historian Patricia Palmieri dubbed an “Adamless Eden” — was an ideal setting for same-sex relationships. At Wellesley College, long-term relationships among female faculty members were common enough to have their own nickname, “Wellesley marriages.” At Vassar College, history professor Lucy Maynard Salmon and librarian Adelaide Underhill shared a home and exchanged love letters.

By contrast, most student romances were short-lived. May Copeland was a hopeless romantic, falling in love with a new senior each year, only to bid each a sad farewell. She expressed her sentiments in verse: “There comes to me a sad regret / That thus our sun of love has set, / So sweet, so short has been our day / But we may cheer our hearts and say, / While sorrow holds us with it’s [sic] fret / Auf Wiedersehn.”

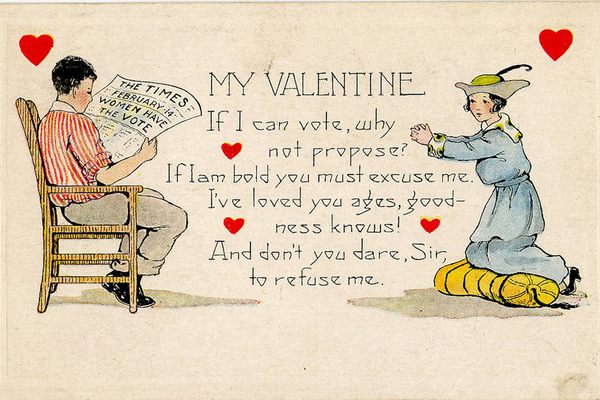

Changing attitudes posed an even greater threat to student romances than graduation day, however. At the turn of the century, emerging theories about women’s sexuality and increased fears about women’s independence heightened social anxieties about women’s relationships. In a post-Freudian and anti-feminist era, female friendships attracted suspicion rather than admiration. In the early 1900s, advice-givers warned that same-sex relationships posed a threat to both heterosexual marriage and the social order.

In response to these concerns, college authorities at Vassar and elsewhere became determined to quash same-sex romance. They replaced student suites with single rooms and sponsored more mixed-gender social events. By 1925, Vassar publications recommended that love-struck students seek psychological help.

Students gradually, if grudgingly, adopted new ideas about same-sex relationships. A student publication, the Vassar Miscellany, reflected changing attitudes. As late as 1900, it featured poetry celebrating student smashes and Valentine’s Day traditions. Over the next two decades, however, student contributions became increasingly critical of crushes, casting them as immature or even abnormal.

In 1890, May Copeland gave and received multiple Valentine’s Day cards. Exulting in her success, she described the holiday as “quite a bit of fun.” May expressed no self-consciousness about same-sex romance in letters home to her family. By contrast, subsequent generations of Vassar students castigated themselves in the pages of their private diaries for their “foolish” feelings for other students, vowing to “overcome” their unseemly “passion” for “kissable” girls. By the 1920s, some Vassarians sent valentines to far-away boyfriends rather than exchanging them with fellow students.

Victorian women’s Valentine’s Day celebrations centered same-sex relationships. In the twentieth century, a rising tide of homophobia curbed celebrations of the “college crush.” But in contemporary America, the rise of “Galentine’s Day” may spell a new era in which women’s relationships again take center stage.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook