Can Street Art Be Moved Without Destroying It?

“Vermonica”—an L.A. fixture for 24 years—was moved without notice, sparking discussions about history, place, and what makes art, art.

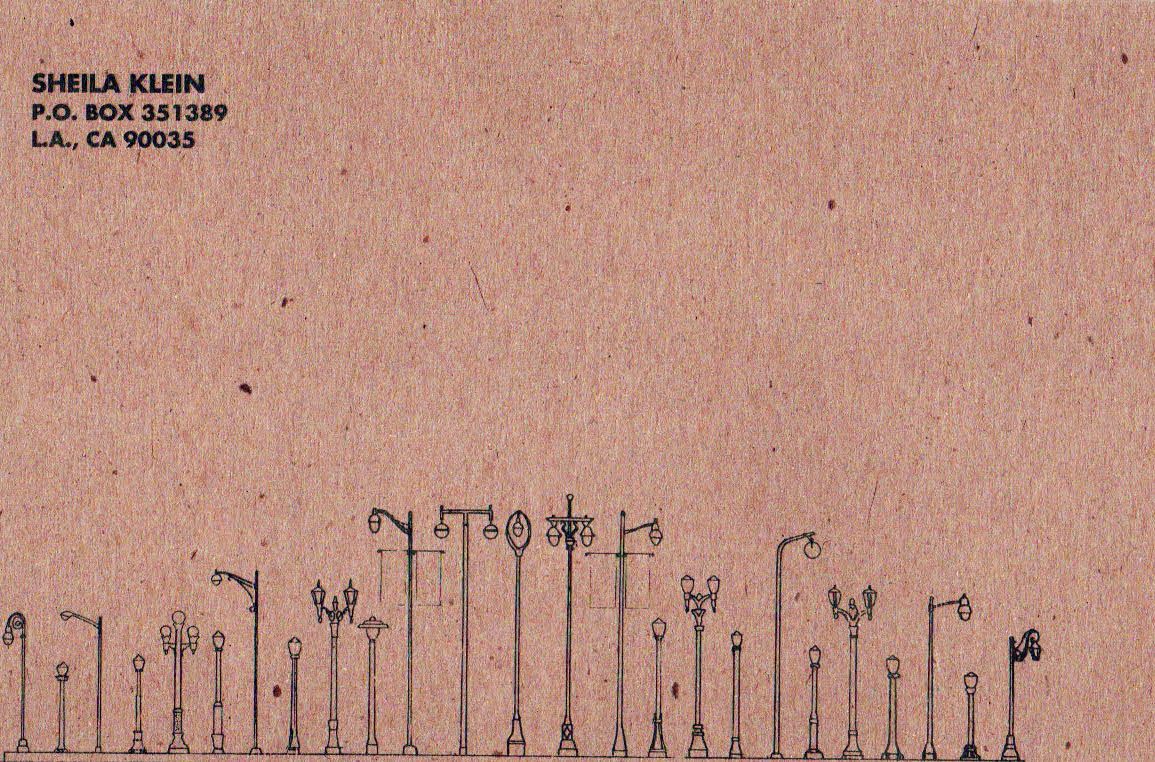

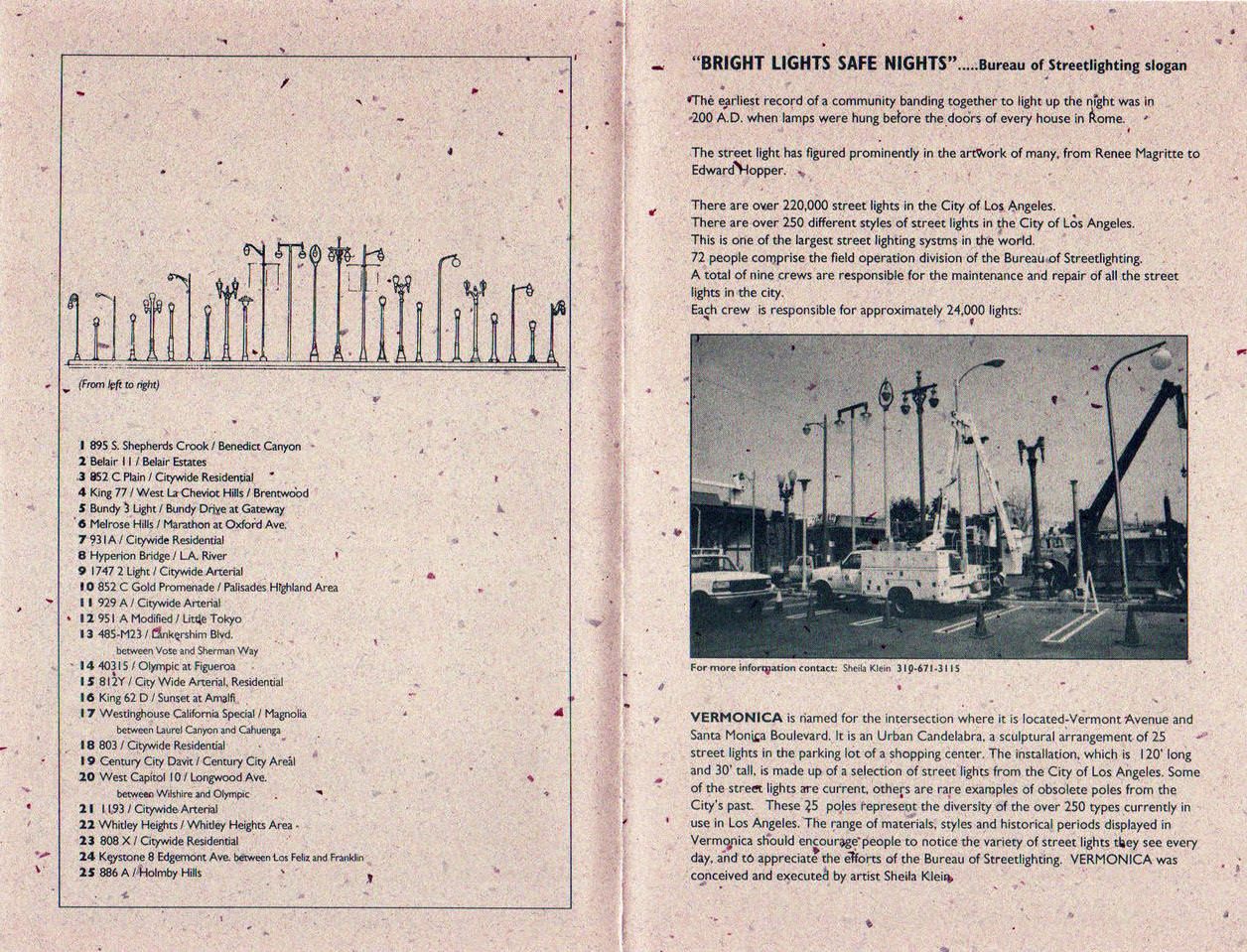

From May of 1993 through late November 2017, if you were looking for the most interesting parking lot median in all of Los Angeles, there was a pretty clear answer. In the lot outside the strip mall at the intersection of Santa Monica Boulevard and Vermont Avenue, lined up on a grassy island, loomed 25 distinct street lights, each sourced from a different part of the city. A crook-necked pole from Benedict Canyon stood shoulder-to-shoulder with a squat obelisk from Bel Air. Baroque lanterns from Olympic Boulevard mirrored dangling globes that once lit Little Tokyo. Some lights dated all the way back to 1925, when the city’s official illuminated-infrastructure department, the Bureau of Street Lighting, was first created. Others were more recent, clones of those that are still visible in their natural habitats.

The lights form an art piece—called Vermonica, after the two streets that cross nearby—created by artist Sheila Klein, with help from the Bureau of Street Lighting and the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs. Intended as a one-year installation, the piece lasted nearly a quarter of a century, buoyed by the ongoing support of the community, and enjoying a consistent influx of new fans who would stumble upon it on their way to the nearby Staples.

Then, just before Thanksgiving, Vermonica disappeared. The poles showed up soon after, about a block away, in front of the Bureau of Street Lighting’s Field Operations office. The Bureau, it later emerged, had been trying to save them: the shopping center that owns the whole strip mall was renovating the parking lot, and had made clear that they would destroy the piece unless it was removed immediately. The Field Office was nearby, and under the Bureau’s control. The move was an effort to protect the art.

But fans, and Klein herself, don’t necessarily think it succeeded. “This is not my piece,” Klein wrote in a statement soon after the move, “and it is no longer Vermonica.” Some fans of the work agree: “Vermonica has been destroyed,” says Richard Schave of the Los Angeles-based tour company Esotouric, who has been working with Klein to try to find some kind of resolution. Others expressed their displeasure on historic preservation Facebook groups. The Bureau, too, describes the relocation as temporary, and is now in talks with Klein about moving the streetlights again. “The final location of the piece and new name will be resolved by the artist,” the Bureau’s assistant director, Megan Hackney, wrote in an email.

The set of lit-up poles currently standing guard over the Bureau building certainly resembles Vermonica. It’s made of the same streetlights, with the same storied origins, arranged in the same order (although they’re now installed on a slight curve). So what was the magic that made Vermonica what it was? Where did it go, and is it possible to bring it back?

In person, Vermonica is almost eerily peaceful. The streetlights are graceful and tall; at night, their lamps glow softly. Klein describes it as “an urban candelabra made of streetlights.” But the piece was also a response to a moment of great aggression: the L.A. Riots of 1992, during which residents clashed violently on the streets of the city after the acquittal of the four policemen who had beaten Rodney King. This particular strip mall was a flashpoint for the conflict: many of the surrounding buildings were burned, and the Korean-American owners of Hollytron, one of the mall’s stores, spent a night shooting automatic weapons into the air from the shop’s roof. “That parking lot—that shopping center—is the site of one of those iconic images of Los Angeles that we forever need to remember, however unpleasant,” says Schave.

Although she had the basic idea in mind before the riots, Klein didn’t know quite where she wanted to put the streetlights until afterward, when she happened to drive through the intersection of Santa Monica and Vermont on her way to a community meeting. “I saw this location that had been burned out,” she says. It was, she thought, the perfect spot for an urban candelabra: “It could be this expression of light, and of history.”

To Schave, this juxtaposition is one of the most vital parts of the piece. “It’s an important site for Los Angeles to meditate on on a daily basis,” he says. ” He compares Vermonica to a menorah: “Light, right? There’s that Hebrew expression, tikkun olam—healing the world.” The piece encouraged such meditation. “And it’s gone. So that sucks.”

Ironically, Vermonica was never supposed to stick around even this long: when it was first conceived, it was meant to be a one-year installation. But from its beginning, the idea has lit something in people, inspiring them to help out and keep it going. When Klein began planning the piece, in the early 1990s, she first sketched out some concept art. “I went to [the Bureau of] Street Lighting and I held up that drawing,” she says. “And I said, would anybody be willing to help me make this piece?”

A few dozen employees agreed on the spot, she says. They ended up donating many hours of their own time. The City’s Department of Cultural Affairs also gave its blessing, along with a $6,000 seed grant. Over the next couple of years, Klein and her volunteers worked together to build Vermonica, scouring the Bureau’s boneyard for historic poles, refurbishing them, and replanting them in the parking lot. By May of 1993, the work was officially complete.

The original plan was to leave Vermonica up for a year. But everyone liked it, so it simply never came down. The Bureau decided not to recollect the poles—instead, they continued to change the lightbulbs. The owners of the nearby shopping center, who had also donated funds to make the piece, kept shunting over enough electricity to keep it lit. And people kept visiting: sometimes purposefully, but often by accident, discovering the work while commuting or out doing errands. (“Every day, people ask me what the streetlights are doing there,” a greeter at a nearby office supply store told the Los Angeles Times in 2003.)

And so what started as a one-year term stretched to two dozen. Locals cherished knowing about it, and visitors enjoyed running into it in such an unlikely place. “It just wove itself into the culture of the neighborhood,” says Klein.

There are also aesthetics to consider. Klein, who has left L.A. and now splits her time between Buenos Aires and the Pacific Northwest, hasn’t seen the new placement in person. But when she looks at images of it, “I cringe,” she says. “They took the materials, and they were very fastidious about putting them in the same order… [but] materials are not art,” she explains. “It’s a subtle thing, maybe, for a lot of people, but it’s kind of caged now. It’s so close to the building … it’s totally wrong.” She’s disappointed that the city didn’t contact her about the problem, and ask her what to do.

It’s unclear whether Vermonica will be able to go back exactly where it was, or even if that’s the best option. What is clear is that everyone—Klein, fans like Schave, the Bureau of Street Lighting, and the Department of Cultural Affairs—would like for the spirit of the piece to stay alive somehow, whether that’s through relocation or by some other means.

Klein has been meeting with the city, although she says they’ve been less responsive of late. “The City is working with Ms. Klein to help find a new home and plan for Vermonica,” Hackney, of the Bureau, wrote. Danielle Brazell, the General Manager of the Department of Cultural Affairs, reiterated: “DCA, the Bureau of Street Lighting, and the Office of Councilmember Mitch O’Farrell are working in partnership with the artist to identify a permanent home and properly bring this piece into the official City Art Collection.”

In the meantime, Klein keeps thinking back to the big party they threw when Vermonica first opened, in May of 1993. “It was amazing,” she remembers. “Street lighting came with all their equipment. The Cultural Affairs people hired a mariachi band. Everybody in the art world, everybody from the neighborhood … It was an incredible party. I hope there will be another party like that when we figure out what the heck to do.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook