How a 70-Year-Old Dino-Size Mystery May Have Finally Been Solved

Was it a teenage T. rex or another species entirely?

For the last century or so there has been a paleontological debate surrounding a single, pointy-toothed dinosaur skull that came out of the Montana rock in 1942. It looked a lot like that most famous of dinos, Tyrannosaurus rex, except much smaller. Eventually it was given a separate genus, Nanotyrannus—“little tyrant”—but some believed it was just a juvenile T. rex all along. Now researchers have examined two more recently excavated individuals, known as Jane and Petey, under a microscope, to see if they could settle the debate for good, and potentially offer insight into how dinosaurs grew and matured.

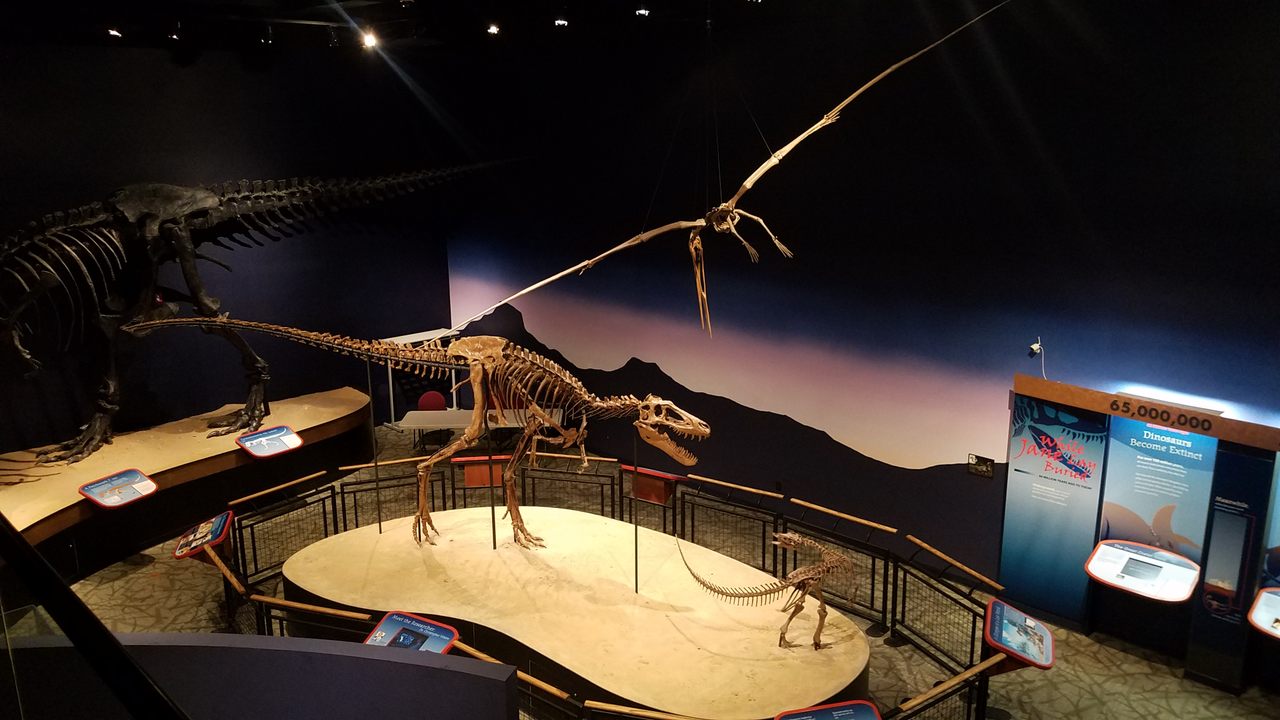

The newer fossils were excavated from the prolific Hell Creek Formation, which stretches across the north-central United States, in 2001 and 2005 by paleontologists from the Burpee Museum of Natural History in Rockford, Illinois.

“Since the 1990s and 2000s, most researchers have agreed [the 1942 skull is] a juvenile T. rex,” says Holly Woodward, a paleontologist specializing in microscopic tissue structure at Oklahoma State University and lead author of the new paper published in the journal Science Advances. “But all the arguments are based on morphology and skull shape, and then when the Burpee Museum found Jane and Petey, not only were there skulls that looked like the earlier one, but also a full skeleton. And that reignited the debate.”

When the older skull was dubbed Nanotyrannus in 1988 by a group of esteemed paleontologists, a prime piece of evidence was the way its skull bones had fused, suggesting that it was an adult. But there’s a lot we don’t know about what happened as dinosaurs matured, and new fossils have a way of challenging old assumptions. When extinct animals are reclassified or renamed, it’s known as getting “sunk” into a different taxon, and it’s not an uncommon occurrence.

“We’re getting to a point, especially in a place like Hell Creek, where we’re starting to get intermediates,” between babies and adults, says Denver Fowler, a paleontologist and curator of Badlands Dinosaur Museum in North Dakota. “It feels like there are a lot of species getting sunk right now.” That is, a lot of specimens once thought to represent new species are getting reclassified as the young of another.

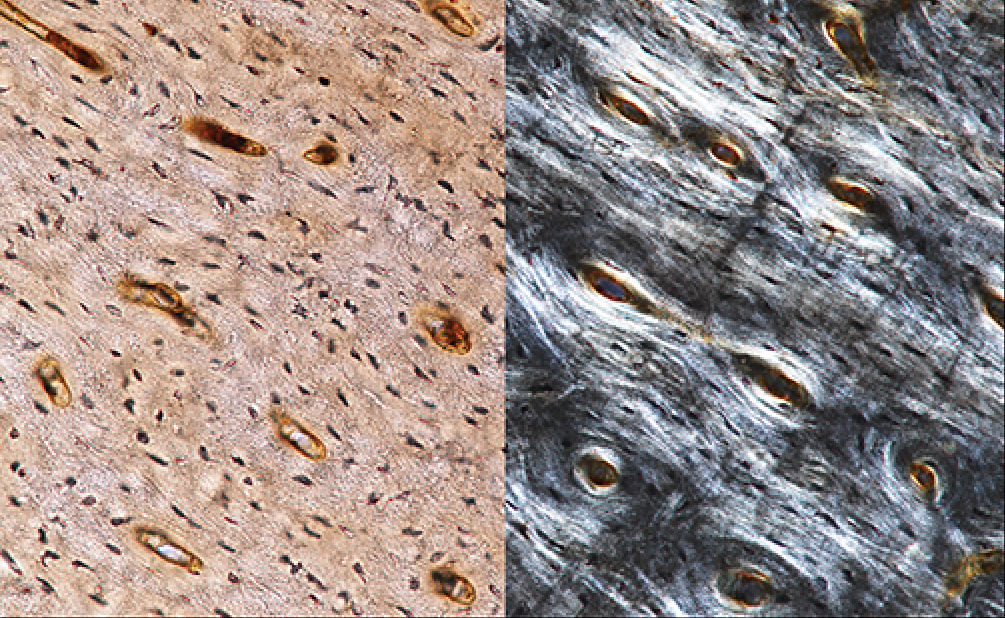

To get a closer look at how dinosaurs and their skeletons change as they grow, Woodward had to, well, look closer—with a microscope. “You can go out and find a fossil and immediately know it’s a fossil, but it’s fossilized all the way down to that microscopic level,” she says. “You can see holes in the bone where blood cells used to be, and you can see bone tissue organization that gives you clues about growth rate.”

Woodward’s team found that the bone tissue of Jane and Petey was richly vascularized, with openings for lots of little blood vessels—a telltale sign of rapid growth, even in modern animals. “A lot of people think of bone as just something tissues attach to, but the bone is living too,” she says. If they had been adults, the team hypothesizes, the bone would have shown patterns more associated with slow and steady growth. The researchers also saw signs that Jane and Petey had slowed and hastened their growth in different years—likely depending on when it was nutritionally sensible to invest the precious calories in it. All of this leads to the conclusion that the two specimens—and the 1942 example as well—are young T. rex individuals, and that the apparent bone plate fusion may have been misleading.

Though the evidence appears to indicate that Nanotyrannus is sunk, it’s hard to keep a dino-size idea down. Science—and more bones from critical, developmental stages of dinosaur life—may do the trick. Or may not.

“It should be wrapped, but it won’t be,” says ReBecca Hunt-Foster, the paleontologist for Dinosaur National Monument in Utah. “People love the idea of Nanotyrannus, and they can’t see the forest for the trees.”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook