5 Spectacular Transportation Failures

Infrastructure, you had one job…

In these modern times, it’s easy to travel from point A to B without paying much mind to the infrastructure supporting the journey. How often do you drive under a bridge and think, thank goodness that bridge wasn’t a couple feet lower, or I wouldn’t have made it? Feats of engineering tend to go overlooked when everything is well-designed and functioning properly. But when roads, bridges, or transit systems break down, that gets people’s attention—and can help put the work of architects and engineers into perspective. With that in mind, here are five classic examples of transportation infrastructure failing, in an utterly spectacular fashion.

The Can Opener

DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA

At first glance, this bridge appears to be an innocent railroad trestle. But this is no ordinary trestle. Built more than two feet below the current minimum clearance standards, it will mercilessly scalp any too-tall vehicle that tries to pass underneath. It’s infamously known among locals and truckers as The Can Opener.

This architectural dysfunction occurs because when the bridge was erected about 100 years ago, no vertical clearance standards were in place. So the bridge stands a mere 11 feet 8 inches above the road, making it dangerously low for modern trucks to pass safely beneath without a cacophonous and melodramatic shave off the top. The bridge claims, on average, one vehicular victim each month.

The Viaduct Petrobras

SÃO SEBASTIÃO, BRAZIL

Looking as though it was miraculously transported from a more urban area, the abandoned Viaduct Petrobras rises out of the lush South American jungle, a testament to mismanaged government spending.

Construction on the Rio-Santos Highway began in the 1960s, and by 1976 the stretch of road was due to be linked to the existing highway. However, plans were altered at the last minute so that the existing road was linked to a coastal route instead, and the newly constructed viaduct was simply abandoned. Over 40 meters tall and 300 meters long, the elevated roadway features tunnels, retaining walls, and a massive concrete foundation all being slowly taken over by the surrounding greenery.

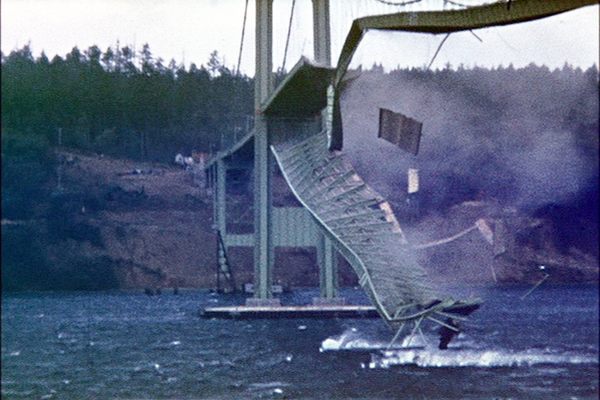

Tacoma Narrows Bridge

TACOMA, WASHINGTON

The original Tacoma Narrows Bridge opened on July 1, 1940, and collapsed into Puget Sound five months later. The common explanation for its collapse is that the bridge’s resonant frequency matched the frequency of the wind, and set the poorly designed bridge on an ever increasing oscillation, twisting and rolling until it eventually collapsed. But this is now known to be false. The real culprit is a phenomenon known as aeroelastic flutter, and though the idea of a feedback loop between the air and the movement of the bridge is correct, it had little to do with the natural frequency of the bridge.

It took the state of Washington about ten years to rebuild the Narrows Bridge, and it was designed so a disaster of this scale would not happen again. The newly rebuilt bridge opened in 1950, longer and wider than the original. Meanwhile, the remains of the original Narrows Bridge are in much the same place they fell. The wreckage has created an artificial reef, and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Bridge to Nowhere

MOUNT BALDY, CALIFORNIA

There’s more than one bridge project that’s been dubbed the “Bridge to Nowhere,” but this one is a classic. It’s a truss arch bridge that was built in 1936 just north of Azusa, California, in the San Gabriel Mountains. During its initial construction, Los Angeles County claimed that the bridge and connected highway would be one of the most scenic roads in America. Unfortunately, these thoughts quickly changed when the road that provided access to the bridge was washed out during a massive flood in 1938, just two years after the bridge’s completion.

The entire project was then abandoned and the bridge was left forever stranded in the middle of the Sheep Mountain wilderness, without having a single car ever cross it. The Bridge to Nowhere remains one of the most bizarre artifacts of the San Gabriel Mountains, unused and alone in the wilderness.

Leinster Gardens False Facades

LONDON, ENGLAND

When the London Underground was being constructed in the 1860s, rather than tunneling under existing buildings, deep tunnels were dug right through the city and then covered up again. But not all of the properties razed to make way for the railway were rebuilt. The houses at 23 and 24 Leinster Gardens were demolished to build the tunnel, but the sacrificed homes were never reconstructed, leaving a rather unsightly hole in an otherwise picturesque block. So a false façade was constructed to conceal the wound.

The façade matches its neighbors in every important detail, except that the windows are painted on, rather than being made of glass. You could live in that neighborhood for years, walking by this address frequently, and still not notice the deception if you’re not looking for it. From the back of the block, however, you can see what’s going on. The houses on either side are braced against each other by a number of sturdy steel struts, and the Underground tracks are visible—and most audible—just below.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook