The Movie Date That Solidified J.R.R. Tolkien’s Dislike of Walt Disney

He went to see “Snow White” with C.S. Lewis.

It’s no secret that J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis were legendary frenemies. But while they may have sparred over fantasy and religion, they shared one little-known viewpoint: a disdain for the works of Walt Disney.

Literary friendships are often thought of in the driest abstract, with learned people of letters sitting in stuffy rooms debating only the most important intellectual issues. But like anyone, sometimes a couple of authors just go to the movies. And on at least one occasion, the architect of Middle-earth and the father of Narnia went and saw Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs together.

According to an account in the J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide, Tolkien didn’t go see Snow White until some time after its 1938 U.K. release, when he attended the animated film with Lewis. Lewis had previously seen the film with his brother, and definitely had some opinions. In a 1939 letter to his friend A.K. Hamilton, Lewis wrote of Snow White (and Disney himself):

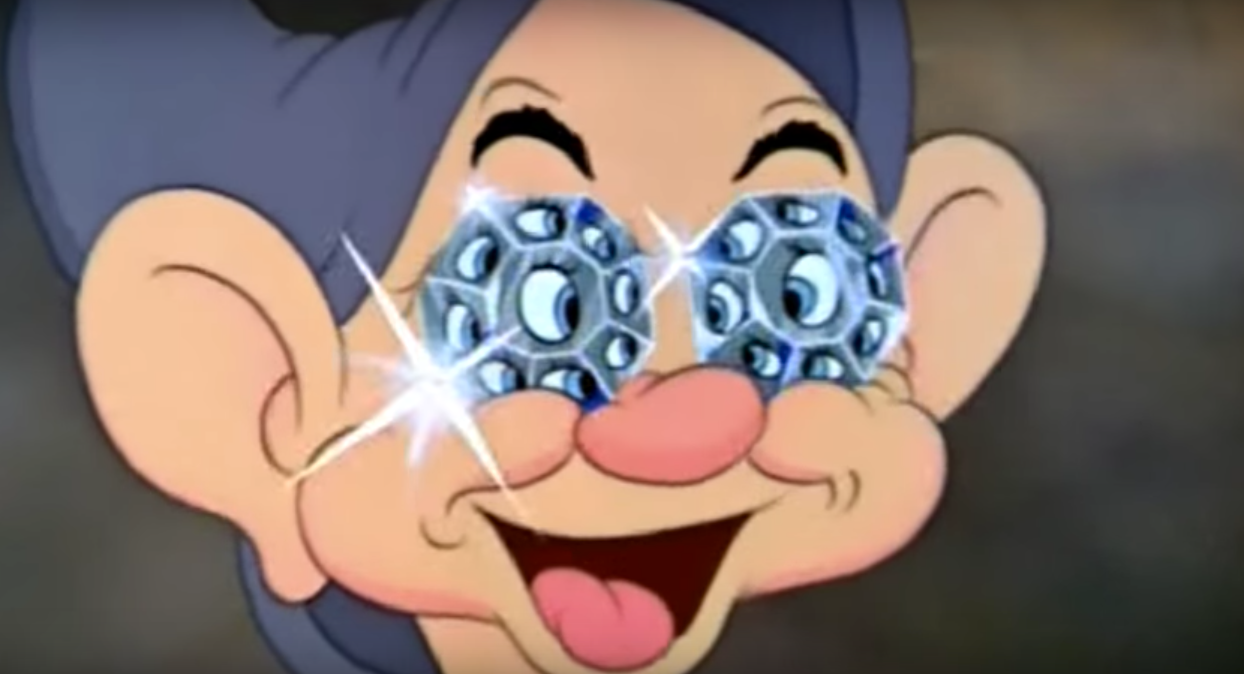

Dwarfs ought to be ugly of course, but not in that way. And the dwarfs’ jazz party was pretty bad. I suppose it never occurred to the poor boob that you could give them any other kind of music. But all the terrifying bits were good, and the animals really most moving: and the use of shadows (of dwarfs and vultures) was real genius. What might not have come of it if this man had been educated–or even brought up in a decent society?

In another instance, Lewis called the evil queen’s design unoriginal, and described the dwarves as having, “bloated, drunken, low comedy faces.”

Tolkien didn’t like the goofball dwarfs either. The Tolkien Companion notes that he found Snow White lovely, but otherwise wasn’t pleased with the dwarves. To both Tolkien and Lewis, it seemed, Disney’s dwarves were a gross simplification of a concept they held as precious. “I think it grated on them that he was commercializing something that they considered almost sacrosanct,” says Trish Lambert, a Tolkien scholar and author of the essay, Snow White and Bilbo Baggins: Divergences and Convergences Between Disney and Tolkien. “Here you have a brash, American entrepreneur who had the audacity to go in and make money off of fairy tales.”

Consider the context here: Tolkien’s book The Hobbit was first released in the U.K. in September of 1937, just a couple of months before Snow White hit theaters in the U.S. Both works highlighted a gaggle of dwarves as major supporting characters, but they could hardly have been more different. Disney’s dwarfs were jolly, goofy miners (hey, Dopey), rooted in the stories of the Brothers Grimm; Tolkien’s dwarves were a grim, mythical race (although not wholly without whimsy), born from Nordic myth. “Isn’t it interesting that Tolkien and Disney, almost concurrently, came up with dwarves that are not evil?” notes Lambert. “I researched, is there any possibility that there was a connection? And there’s not.”

Across the ocean and seemingly independent of one another, two of the greatest storytellers of the 20th century had a case of parallel invention, although this is not to say that Tolkien and Disney were unaware of one another. There are unflattering references to Disney’s early cartoons in Tolkien’s letters, and according to Lambert, Tolkien would most certainly have been aware of Snow White before its release. “I don’t have any way of proving this, other than the things he’s written on Disney in the general sense, but I suspect [Snow White] irritated the heck out of Tolkien,” she says.

Tolkien’s opinion of Disney didn’t get any better over the years. In a number of letters dated after his Snow White date with Lewis, Tolkien refers to Disney’s works as “vulgar.” Tolkien also believed that fairy tales had become hopelessly infantilized, noting in his 1947 essay On Fairy-Stories that “the association of children and fairy-stories is an accident of our domestic history.”

Years later, in a 1964 letter to a Miss J.L. Curry at Stanford University, likely spurred on by the controversy surrounding Disney’s treatment of Mary Poppins, Tolkien further laid bare his true feelings on Disney’s work. He described Disney’s talent as “hopelessly corrupted,” writing, “Though in most of the ‘pictures’ proceeding from his studios there are admirable or charming passages, the effect of all of them is to me disgusting. Some have given me nausea…” He goes on to call Disney a “cheat,” noting that while he too had a profit motive behind his work, he wouldn’t stoop to working with Disney.

Just two years later, Joy Hill, a representative of Allan & Unwin, Tolkien’s publisher, would approach Disney Studios about turning the Lord of the Rings trilogy into an animated film. Disney Studios declined, thinking that it would be far too expensive to produce. The Tolkien Companion assumes that this conversation occurred without Tolkien’s permission.

The relationship between Tolkien and Lewis is often viewed in light of their religious differences, or contrasted by nerdy arguments about Narnia vs. Middle-earth. But in the eminently relatable experience of going to see a Disney movie that they both disliked, their relationship seems less fantastical, and all the more human.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook