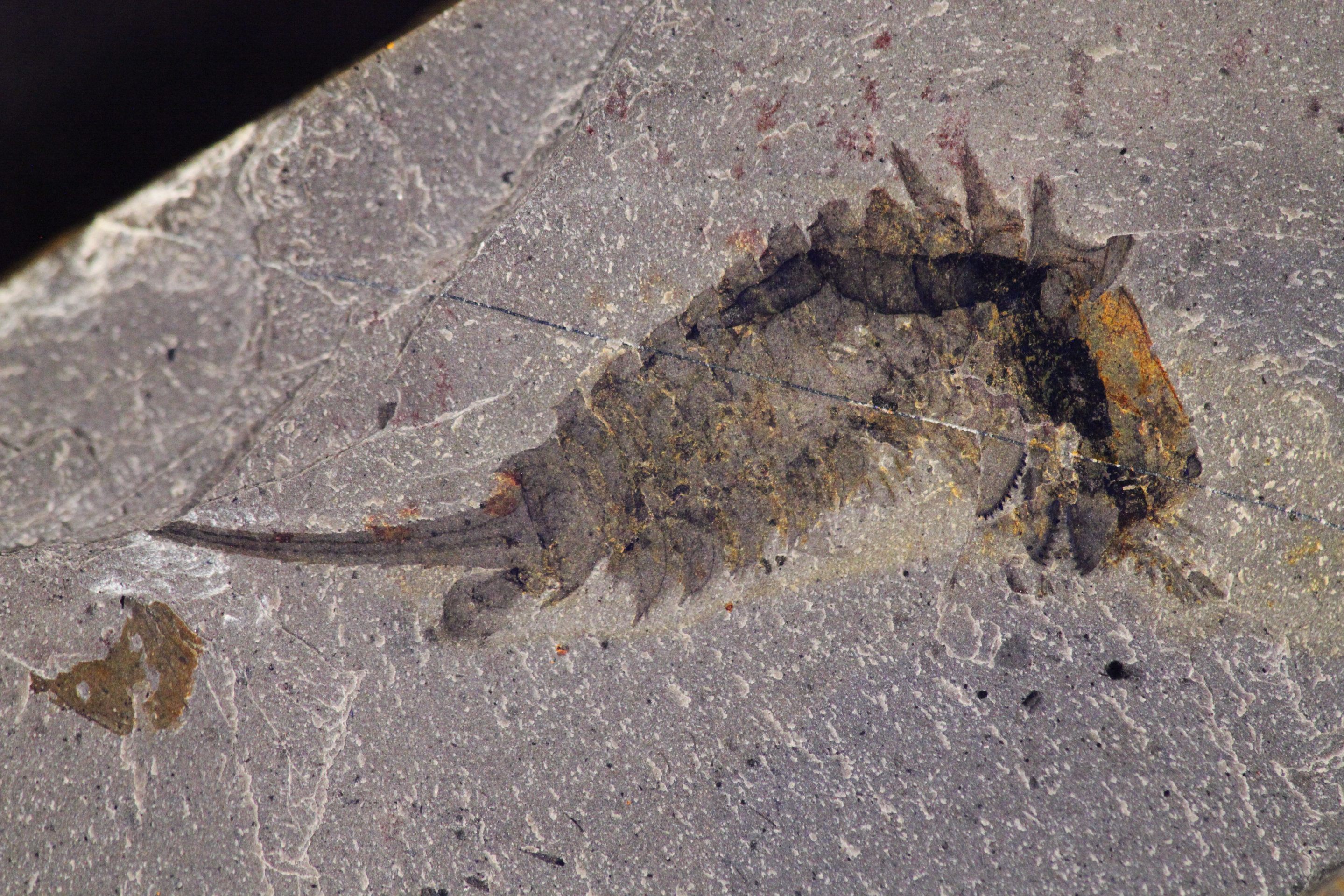

Found: A Tiny, Terrifying Sea Monster From 500 Million Years Ago

Small, but fierce and well-armed.

We think Habelia optata bears a striking resemblance to Napoleon Bonaparte. Both were small (one a little smaller than the other) and resplendent in bicorne headwear, and considered quite fierce. Though under scrutiny the similarities break down a little. Bonaparte lived and died above sea level in the 19th century, while H. optata did its rampaging underwater, 508 million years ago. Bonaparte had two legs, H. optata at least 10, with another 14 squeam-inducing appendages jutting out of its head. This fingernail-length predator, first discovered in fossils more than a century ago, has long confused scientists—but a recent study from Canadian researchers has dug into its anatomy and found kinship with sea scorpions and horseshoe crabs.

The little beast lived not long after the “Cambrian explosion”—a period of incredibly quick evolutionary change, when sponges with skeletons, millimeter-long mollusks, and other curious creatures ruled the ocean floor. Like a modern-day shrimp or lobster, its body was segmented, with an armored shell and jointed legs. The appendages on its head, scientists say, make a vestigial appearance in today’s arthropods, like a crustacean appendix. “We can now explain why, for instance, horseshoe crabs have a reduced pair of limbs—the chilaria—at the back of their heads,” said researcher Cédric Aria, a recent doctoral graduate at the university of Toronto, in a statement. “Those are relics of fully-formed appendages, as chelicerates seem to originally have had heads with no less than seven pairs of limbs.”

Most creatures in its evolutionary neighborhood—including sea spiders, arachnids, and extinct sea scorpions—have legs that are on the same body segment as their heads, “while Habelia still had walking appendages in its thorax.” As a result, the tiny predator could use its head appendages for a range of specialized activities—bristle-like spines to grasp prey, a toothy plate for chewing, and leg-like feelers for sensing the world around it. “This complex apparatus of appendages and jaws made Habelia an exceptionally fierce predator for its size,” said Aria. “It was likely both very mobile and efficient in tearing apart its prey.” Now imagine one of these Napoleon’s size. Yikes.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook