This Man-Made ‘Meteor-Wrong’ Fell From Space

It wasn’t a meteorite; it was a piece of space trash.

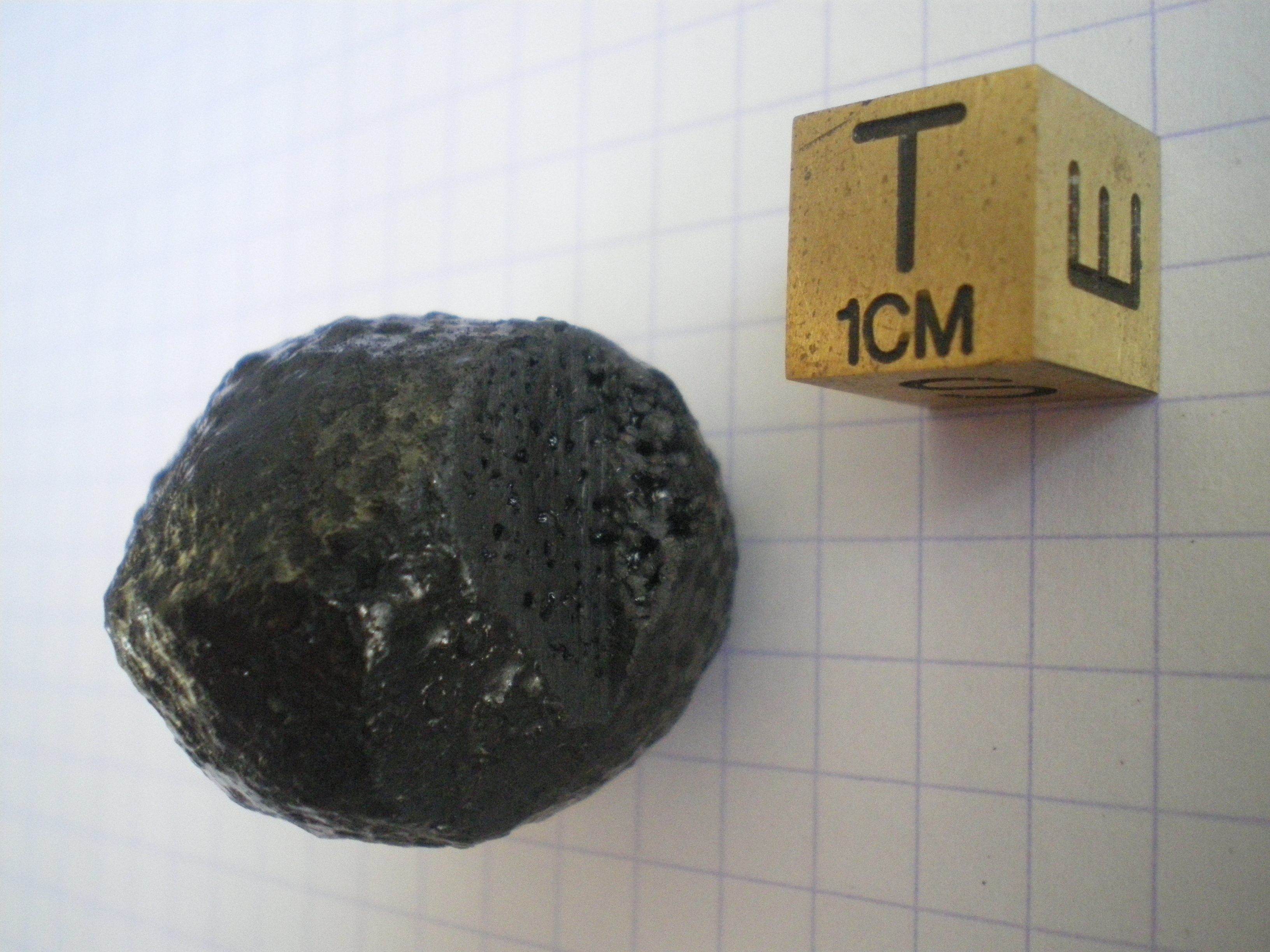

This fell from space. (Photo: J.M. Trigo-Rodríguez/ICE, CSIC-IEEC)

One winter night in 2012, in a small Spanish city not far from Barcelona, a 10-year-old girl saw something streak through the sky and fall to Earth. The object, whatever it was, was glowing.

The little girl waited, until she could pick the object up and bring it home. She showed it to her relatives, and they wondered. Where had this object had come from? What exactly was it that had fallen from the sky?

The family brought the girl’s discovery to a local museum. They were directed to an astronomical organization, who handed the object to the Institute of Space Sciences. To the scientists there, who specialize in studying meteorites, one thing was immediately clear. This object, round, black and rock-like, was not a meteorite.

If it were a meteorite, it would have been heavier. The scientists were intrigued. “The sample was so weird and challenging we decided to study it carefully,” they wrote, in a report presented at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (from which the details above are drawn).

The scientists wanted to preserve the object, but they needed to know what it was made of. They sliced into one corner, to obtain thin sections of the material. When they saw the interior, they were even more certain it was not a meteorite. First, it didn’t look like the interior of “any known meteorite,” they wrote. Also, it had bubbles inside.

Those bubbles indicated that this object was likely man-made, and when the scientists analyzed its composition, they found more evidence to back up that theory. It was made mostly of carbon and sulfur—again, nothing like any known meteorite. Plus, it contained other unusual elements that hinted to the scientists that humans had something to do its creation.

They concluded that it was probably a “sulfur-carbon composite,” of the type that’s increasingly being used to make rocket ships. These composites are lighter than metal and have other properties that make them attractive as rocket-ship materials. Apparently, they also can survive atmospheric re-entry, which burns up much of the trash that we leave orbiting in space. “This could represent the first description of such a type of residue arrived to Earth’s surface,” the scientists wrote.

When space debris does come back to Earth, it tends to be partially melted aerospace or rocket pieces that are easy to distinguish from space rocks. This piece of space trash was something new: a man-made object that seemed deceptively like an actual meteorite.

There’s a word for a rock or object that a person thinks is a meteorite, but actually is not: a meteor-wrong. Usually, a meteor-wrong is a geode or some other rock that did not fall from the sky. But given the amount of stuff that we’re putting into space and leaving there, this new “meteor-wrong,” which actually did fall from the sky, likely won’t be the last of its kind.

Already, the Spanish scientists have studied another case of these composite melted materials, and in the future, more kids may have to puzzle over the origins of falling pieces of sky. Is it a rock that traveled far from the reaches of space to arrive on Earth? Or is it a piece of human invention that we flung upwards and that eventually, eventually, was pulled back in by gravity, until it fell down to ground?

To see actual meteorites, join us on April 16 for Obscura Day at the UCLA Meteorite Collection.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook