This Cartoonist Mapped the Tumultuous World of 1920s Greenwich Village

The neighborhood teemed with “temperamental intellectuals.”

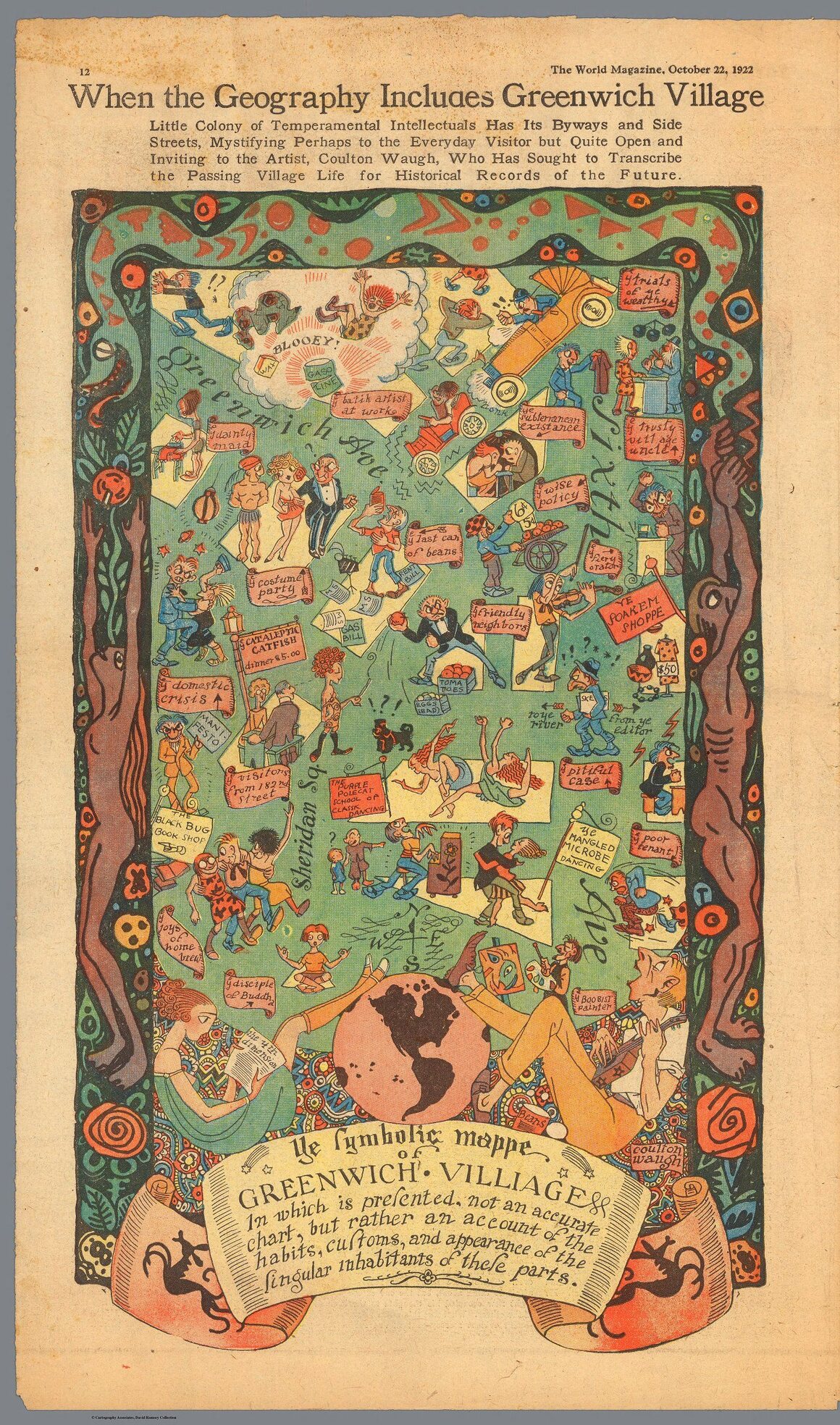

In the 1920s, Greenwich Village was a “little colony of temperamental intellectuals.” [All photos courtesy of David Rumsey Map Collection]

The countercultural reputation of Lower Manhattan’s Greenwich Village was cemented in the 1920s, decades before the flower children and musicians of the 1960s ever called it home. Now dominated by luxury housing and college students, the neighborhood pocketed within Broadway, Houston Street, 14th Street, and the Hudson River teemed with artists and radicals in search of a place that would support their ideas nearly a century ago.

“During these years, the Village acted as a magnet which drew a wide variety of people with one quality in common, their repudiation of the social standards of the communities in which they had been reared,” Vassar College history professor Caroline Farrar Ware wrote in her 1935 book Greenwich Village, 1920-1930.

While descriptions and records tell us of the area’s history, cartoonist Coulton Waugh’s vibrant and comical map illustrates just how lively and eclectic Greenwich Village was in the 1920s. Waugh’s symbolic map—which he denotes as “Ye symbolic mappe: Greenwich village”—is an interpretation of the habits and customs that were commonly seen by the “Villagers.”

The pictorial map, which appeared in the October 1922 issue of The World Magazine, shows scenes along Sixth Avenue, Greenwich Avenue, and Sheridan Square with short descriptions next to each drawn character. The whole spread is flanked by a snake, Adam, and Eve—perhaps alluding to the birth of a new paradise and way of life.

Greenwich Village, the art capital of the world.

Like several other New York City neighborhoods, Greenwich Village began as a home for immigrants. Right before World War I, the rate of immigrants coming to America was at a million a year. Americans faced a depression, Prohibition, unemployment, and in subsequent years, the trauma of war, Ware notes. Many individuals fled to Greenwich Village, abandoning their homes “in protest against its hollowness or its dominance and had set out to make for themselves individually civilized lives,” she wrote.

Born in Cornwall, England, Waugh was one of the many immigrants who came to the United States in 1907. While the cartoonist lived in Provincetown, Massachusetts when the map was published, he had previously lived in New York City and attended New York’s Art Students League. In addition to creating pictorial maps and charts, he also painted landscapes of the Hudson Valley and designed fabrics.

Passionate orators can easily be found among the artists in 1920s Greenwich Village.

Waugh is perhaps most famous for his comic strip Dickie Dare and his 1947 book The Comics, which is the first major study of the field. In The Comics, he wrote:

“Comic books may emerge as the most natural, the most influential form of teaching known to man…. Surely they would be justified if only to keep alive our priceless national art of laughter.”

His comic style can be seen in the colorful character sketches of the Greenwich Village map. Waugh, who was about 26 years old when he illustrated the chart, saw Greenwich Village as a “little colony of temperamental intellectuals” that mystified visitors and embraced artists.

The Village was never short of parties, cabarets, music, and shows.

Vaudeville theaters, such as the Greenwich Village Follies, attracted dancers, musicians, and actors. At the same time, a steady stream of artists and writers matriculated into the neighborhood. Art, sex, and a disdain for the pursuit of wealth were key points that defined the morale of the area, Ware writes.

The literary and artistic community in Greenwich Village was a fairly tight-knit group, eating together, criticizing each other’s work, and sharing a common bond that made them feel separate from the rest of the world.

In general, the opinion of the neighborhood was that “there are just as many people out of jail that ought to be in as there are in jail,” Ware wrote.

In general, the opinion of the neighborhood was that “there are just as many people out of jail that ought to be in as there are in jail,” Ware wrote.At the time, Greenwich Village was notorious for its crime ridden streets, with many residents having spent time in jail. Ware documented the account of a policeman who had been patrolling the streets of Greenwich Village for 20 years. He said:

“My opinion of the people on this street is that from five years up to sixty they are all thieves. They’re all born criminals; I wouldn’t trust any of them over three years old. You try and do something with them! It’s no use; you might as well work on that sewer out there.

You see the tin water drains on the church there? Well, they were all copper once, but the kids stole them all, and when the priest tried to chase them, they threw stones and broke the church windows. In ten years they’ll all be gunmen and gangsters.”

Visitors easily stuck out amidst the hoards of artists and writers.

Villagers had a distaste for outsiders, particularly “bourgeois people” from northern neighborhoods of Manhattan who knew “nothing of art, but like to wear flowing ties and live in the midst of temptations,” notes Ware.

However, these individuals began invading the Village, driving up the low rents. In 1922, the American League of Artists reported that prices for studio apartments had shot up so high that poor, struggling artists were starting to be pushed out of the little colony in New York City.

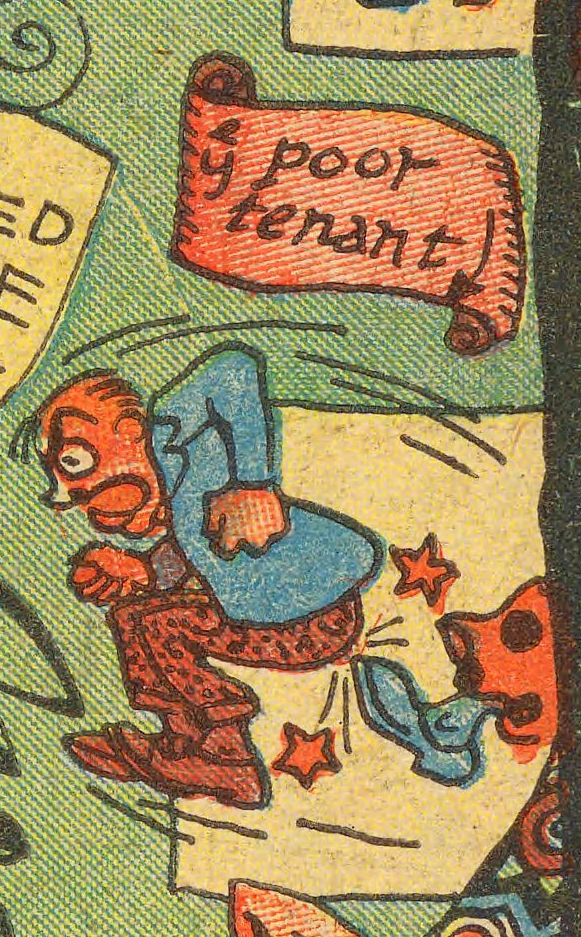

A poor tenant gets the boot.

A poor tenant gets the boot.After World War I, the bohemians of the 1920s drifted away from their creative paradise. In her 1935 book, Ware questioned if the Village could ever be an artistic capital again: “Has the artist colony of the Village been supplied with new blood as the years have gone by?”

Even though Greenwich Village is a very different scene these days, Waugh’s map memorializes the characters—and character—of the neighborhood in 1922.

Map Monday highlights interesting and unusual cartographic pursuits from around the world and through time. Read more Map Monday posts.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook