Object of Intrigue: The Possibly Viking Runestone of Massachusetts

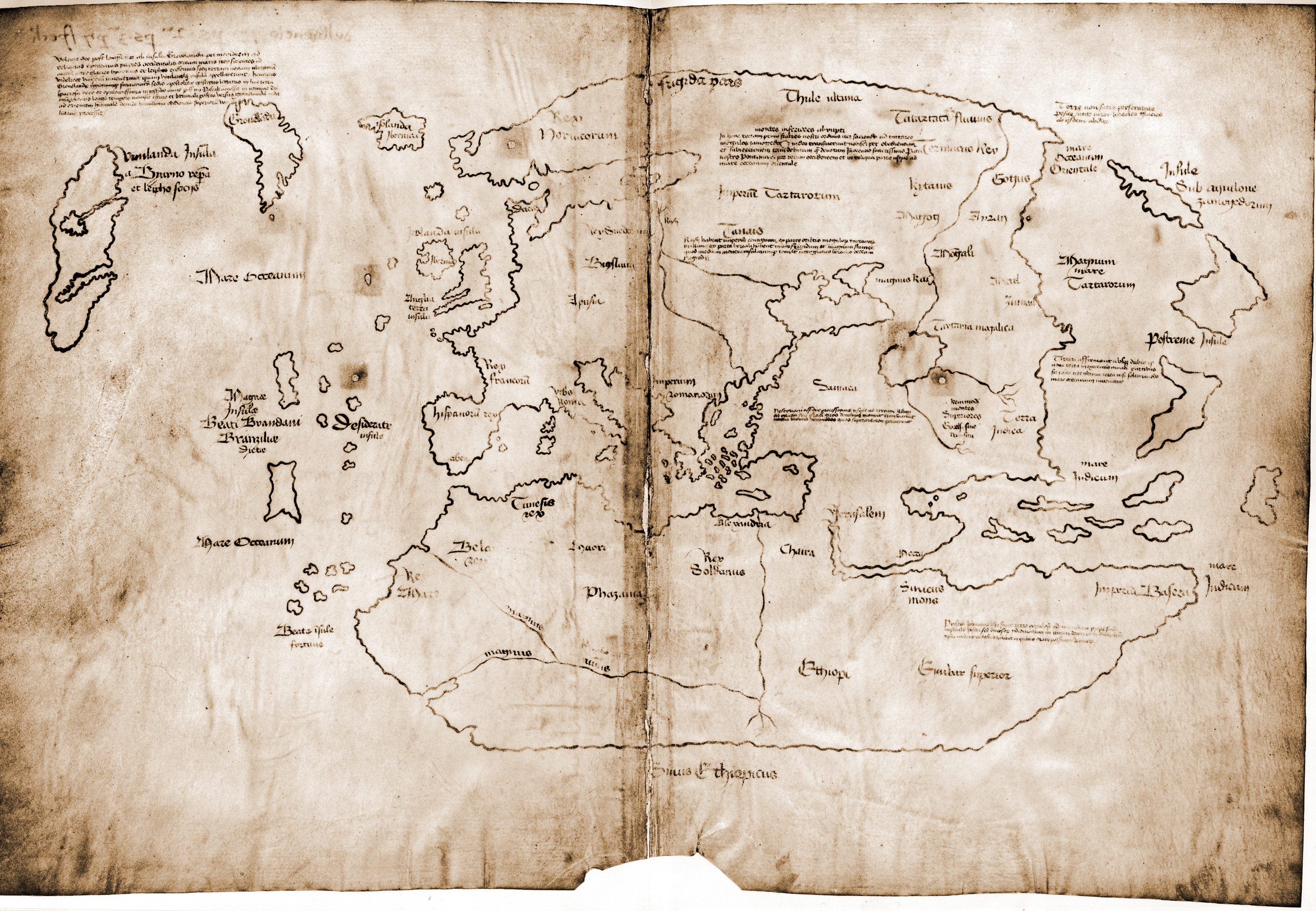

A map of Vinland: the first known depiction of the North American coastline. (Photo: Yale University Press/Public Domain)

On a November afternoon in 1926, Joshua Crane, the sole resident of Noman’s Land Island, Massachusetts, spotted something in the open Atlantic Ocean. According to the Weird Massachusetts travel guide, the tide was particularly low that day so that many of the large boulders normally obscured by the water’s edge were sitting high and dry. Crane identified a large black rock with strange, almost alien-looking markings glinting in the twilight.

It was far out of Crane’s expertise to decipher these markings, so he contacted Edward F. Gray, a historian and photographer working on a book about purported Norse voyages to the Eastern Seaboard. Gray made the long trip out to Noman’s Land, and, managed to snap a few shots of the rock and the resplendent markings in question. To Gray, the markings seemed to match the profile of medieval Norse runes, so he sent his photos to some experts at Oslo University. What the professors came back with was certainly interesting–and had the potential to throw three centuries of accepted history on its head.

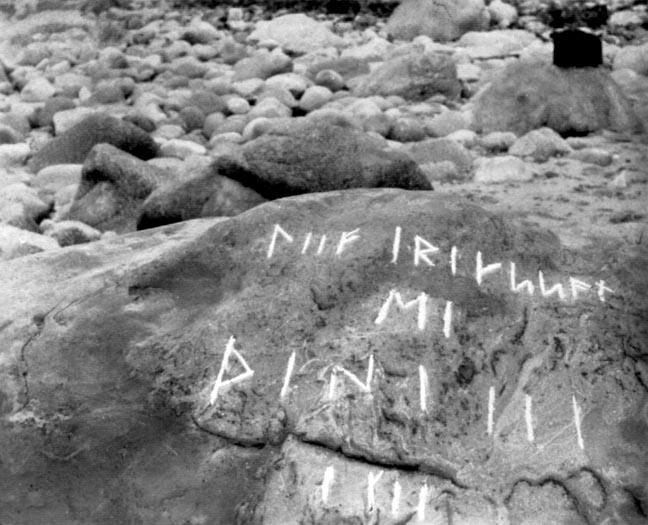

1926 photograph of the Runestone. (Photo courtesy of the Martha’s Vineyard Gazette)

1926 photograph of the Runestone. (Photo courtesy of the Martha’s Vineyard Gazette)

Once deciphered, the text read, “Liif Iriksson, MI.” Gray thought he had hit the jackpot. Could Leif Eriksson—celebrated as the first European to step foot on North American soil—really have etched his name into this Massachusetts stone?

Unfortunately, this wasn’t the conclusive proof of Norse settlement that Gray hoped it would be. “Liif Iriksson” was written in old Norse—the language spoken at the time—but the date (1001) was recorded in Roman numerals. It’s technically possible that members of Eriksson’s party could have learned the Roman system through trade with Germany and other southern European nations. But it’s highly unlikely they would have used numerals to record the inscription.

1893 painting, by Christian Krohg, of Leif Eriksson discovering North America. (Photo: National Gallery of Norway/Public Domain/WikiCommons)

1893 painting, by Christian Krohg, of Leif Eriksson discovering North America. (Photo: National Gallery of Norway/Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Much of the information modern historians have of Norse voyages to North America comes from the Vinland Sagas, which were first committed to writing in the 13th century. Full of contradictory details and fantastic scenes, the Sagas describe a series of ever-more daring voyages made by intrepid Icelanders that took place in the 9th and 10th centuries. While it is generally agreed upon that a group of Icelanders erected a seasonal settlement on Newfoundland in the last gasps of the 10th century (now a World Heritage Site, L’Anse Aux Meadows), there is little consensus about where else the Vikings may have explored.

According to the Sagas, Bjarni Herjolfsson set forth from Iceland en route to Greenland. He was blown off course by westward winds, where, after days lost at sea, he sighted a mysterious new continent—now believed to be the eastern coast of Canada.

The Gokstad longship at the Oslo Viking Ship Museum. Able to withstand heavy seas and carry cargo, yet light enough to portage, these boats allowed the Vikings to reach North America. (Photo: Karamell/WikiCommons)

The Gokstad longship at the Oslo Viking Ship Museum. Able to withstand heavy seas and carry cargo, yet light enough to portage, these boats allowed the Vikings to reach North America. (Photo: Karamell/WikiCommons)

A few years later, around the year 1000, Leif Eriksson himself set off with a crew of men to try to settle this new land. He first came to a barren, rocky place he named Helluland, or “Land of the Flat Stones.” Heading south to warmer and more forgiving climes, Eriksson and his crew reached a densely forested coastline, with plenty of lumber and freshwater. Nicknaming this land Markland, or “Forest Land” Eriksson wasn’t fully convinced it was the best place to build a camp, so the explorers continued south.

The foreboding coastline of Noman’s Land Island. Completely uninhabited and administered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service. (Photo: Gore Lamar, USFWS/Public Domain/WikiCommons)

After two days sail, Leif and company found their own version of Valhalla. From Section 1, Chapter 4 of the Vinland Sagas:

“[T]hey sighted another shore and landed on an island to the north of the mainland. It was a fine, bright day, and as they looked around, they discovered dew on the grass. It so happened that they picked up some of the dew in their hands and tasted of it, and it seemed to them that they had never tasted anything so sweet.”

As the men set up camp, one of their party, a German by the name of Tyrker made a startling discovery:

“I did not go very far beyond the rest of you, and yet I have some real news for you. I found grape vines and grapes!”

Eriksson could not believe his luck, and he set out to make quick work of harvesting. Spending the winter at this new land, dubbed “Vinland” for its plethora of fruit, the Vikings loaded their boat full of grapes for the long return trip to Iceland.

While most experts believe that L’Anse Aux Meadows is the only extant Norse camp in North America, and thus the physical setting of the mythical Vinland, there is a cohort out there who believe that it was nothing more than a staging ground for further exploration—and that there are many more Norse settlements out there.

The World Heritage Site L’Anse Aux Meadows. The only known Norse settlement in North America. (Photo: D. Gordon E. Robertson/Wikicommons)

The World Heritage Site L’Anse Aux Meadows. The only known Norse settlement in North America. (Photo: D. Gordon E. Robertson/Wikicommons)

A spate of findings during the Norse Revival period in the late 19th and early 20th centuries catalyzed public interest in alternative history theories. A rock in Minnesota–the Kensington Runestone—was uncovered in 1898 by a farmer, who believed that this was proof the Vikings made it to Minnesota. There’s even a series of stones that was uncovered in rural Heavener, Oklahoma, however unlikely it is that seafaring Vikings decided to sail up the Arkansas River and settle on the Great Plains.

Most experts rationalize these findings as hoaxes, or even misinterpreted Native American art. Yet, one of the cornerstone pieces of evidence cited for the Vikings in North America theory lies in the tidal zone of Noman’s Land Island, a sandy, uninhabited speck in the Atlantic Ocean, three miles off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard. The kicker is that no one is allowed access to study it.

Reached by email, Victor Mastone at the Massachusetts Department of Underwater Archaeology (BUAR) said that the issues around the “Norse Rock of Noman’s” have been debated in front of the board on numerous occasions. Hoax or not, the BUAR considers the object to be of historical significance.

In 2007, a team from the Historical Maritime Group in New England proposed to study the rock in-situ. Minutes from the meetings suggest that the proposal was rejected on a number of grounds: firstly, because Noman’s Land was used as a bombing range during the Cold War, the team will risk running into unexploded ordinance. Secondly, the US Fish and Wildlife Service now administers the island as a sanctuary for migratory birds, and all non-essential access to the island is banned by the government. Thirdly, the local Wampanoag tribe considers the island to have historical significance, and do not want the stone disturbed.

The coastline of Martha’s Vineyard. (Photo: Alberto Fernandez/WikiCommons)

In 2013, another proposal was levied in front of the BUAR. This time, the proposer was none other than Scott Wolter, a forensic geologist and host of the pseudo-scientific archaeological show America Unearthed on the History channel. Wolter proposed to assemble a team to remove the rock, and put it on permanent display in a museum on Martha’s Vineyard, so it could be safeguarded for further study. The BUAR, as well as the historic preservation commission of the Wampanoag tribe, jointly shut down the request.

The reason why the Noman’s Land Island runestone remains so integral to the Vikings in North America theory is due to the supposed similarities between the landscape of Martha’s Vineyard and the descriptions of the legendary “Vinland” itself. Martha’s Vineyard does have milder winters (due to its proximity to the Gulf Stream), and did have abundant wild grapes before it was widely colonized. Some historical detectives even believe that Martha’s Vineyard is a perfect match for the topographical features—including accounts of surrounding islands—described in the Vinland Sagas.

The Vikings may or may have not landed on Noman’s that fateful summer in the year 1001. One thing is for certain: severe isolation, and a tangle of bureaucratic roadblocks govern access to the Noman’s Land Island runestone. In all likelihood, this mystery will never be laid to rest.

Composite photo of Noman’s Land Island, taken in 1971 when the island was bombing range. (Photo: University of Massachusetts/Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Composite photo of Noman’s Land Island, taken in 1971 when the island was bombing range. (Photo: University of Massachusetts/Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Update, 6/17: An earlier version of this story incorrectly referred to the Viking longship as a replica, when it is in fact authentic. You can see more information about the ship here. We regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook