The Mystery of the Mule Deer

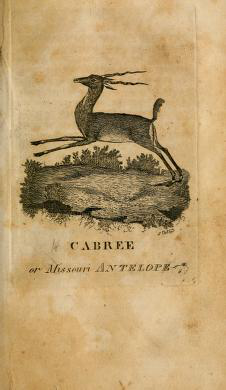

From The deer of all lands, 1898, Richard Richard Lydekker (Image: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

For Neal Woodman, the mystery began with a shrew. But it led to an eccentric 19th century biologist, an apocryphal journal, and, ultimately, one of the American West’s most iconic species.

For about five years now, Woodman, a research biologist and curator with the U.S. Geological Survey and Smithsonian’s natural history museum, has been trying to unravel the mystery of the mule deer and how it first became known to science. In 1817, the mule deer (a more attractive animal than its name would indicate) was first described and given a scientific name by Constantine S. Rafinesque, a botanist and zoologist who had a particular passion for identifying new species. The only problem: Rafinesque’s source for information was a journal written by a Canadian fur trader named Charles Le Raye, who had been captured by a Sioux tribe and, as their prisoner, traveled to places like present-day North Dakota and Montana before even Lewis and Clark had reached them.

That would make Le Raye the first non-native person to explore and document parts of the American West. But when Woodman began investigating the journal, things were not right. “It turns out the whole thing is a fraud,” he says.

A mule deer buck (Photo: Pi-Lens/shutterstock.com)

A mule deer buck (Photo: Pi-Lens/shutterstock.com)

Woodman is a shrew expert, and he first started sniffing around Rafinesque’s work when he came across a shrew species called Sorex dichrurus, a name that originated with Rafinesque. Woodman didn’t know that species of shrew, and as he checked through his reference books, he found that it didn’t show up anywhere.

There was a simple reason. Rafinesque specialized in plants, mollusks and fish, and “he wasn’t a very good mammalogist,” says Woodman. The species he identified as Sorex dichrurus was not, in fact, a shrew. It was a type of jumping mouse.

While researching Rafinesque, though, Woodman noticed that he had sourced many of his species to the captivity journal of Charles Le Raye. Those species included the mule deer, which are indigenous to North America and characterized by their almost comically large, mule-like ears. They’re considered, as the National Wildlife Federation puts it, “among the most beloved and iconic wildlife of the American West.”

But when Woodman went to find out more about Le Raye’s journal, he surfaced a paper from 1983, published in an obscure journal covering South Dakotan history, that showed, in great detail, that the journal was fake. In many places, it was plain wrong: it “mixed up the customs and material goods of the native tribes and confused the geography of the upper Missouri River region,” Woodman wrote in a paper recently published in Archives of Natural History. Which meant, potentially, that for almost two centuries, scientific understanding of the mule deer had rested on entirely fabricated evidence.

“This is an iconic mammal of the West,” says Woodman. “And it was named based on a fraudulent story.”

Constantine S. Rafinesque (Image: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

It was a compelling story, though. Le Raye’s writing was published as part of a larger work, A Topographical Description of the State of Ohio, Indiana Territory, and Louisiana, which was released in 1812 and was a sort of guidebook for settlers of those territories. Le Raye, the tale went, had been heading from a settlement on the Illinois River to trade with the Osage nation, in Missouri, when he was captured. As a prisoner of a group of Sioux people, Le Raye traveled to what’s now the border of South Dakota and Iowa, up into North Dakota, and all the way to Montana’s Powder River, before he escaped. He kept a journal the entire time, which Jervis Cutler, the writer of A Topographical Description, supposedly obtained when they met a few years later, traveling to New Orleans.

Captivity narratives, both real and made-up, were common in early 19th century America, so this one wouldn’t have seemed obviously false. It did have one important distinction, though. Le Raye’s capture was dated to 1801 and his escape to 1805. Since Lewis and Clark didn’t begin their journey until 1804, the story puts Le Raye in these regions well before their famous expedition.

At the time, it wasn’t uncommon for scientists to name species without having seen them or collected a specimen. As explorers reported back from faraway places, scientists would read their descriptions of species and determine if they were distinct from currently known creatures. In America, naming new species had a nationalist purpose, too. “The U.S. is basically a Third World country trying to show it’s worthy of respect,” says Woodman, “Part of their independence is saying: Our marmot isn’t the same marmot as yours. Our bear isn’t the same as your bear. In fact, we have this grizzly that’s huge.”

Rafinesque, who was born in Constantinople and raised in Europe, took up that task with an immigrant’s zeal. He was also trying to prove a scientific point—that species weren’t necessarily static. “Rafinesque, in some ways, is an early evolutionist, although they didn’t have that term and those thoughts hadn’t coagulated yet,” says Woodman. He was pushing the idea that there was more biological diversity out there in the world than anyone had expected. But he was also extremely credulous—so much so that John James Audubon once duped him into naming invented species in a scientific publication. So, it’s unlikely that he even questioned Le Raye’s account.

From a taxonomy perspective, though, Rafinesque did everything right. He named the species in good faith. He followed the acceptable rules of scientific research at the time. But, Woodman wondered what it meant if the account was fraudulent. Certainly, mule deer aren’t made up: Le Raye’s description fits with what we know of the species today. So, was Cutler just lucky when he fabricated Le Raye’s account? Was it totally made up? Or was it connected, in some way, to real animals?

An illustration by Jervis Cutler. (Image: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The answer, as Woodman reported in a 2013 paper, was that the description of the mule deer did, ultimately, come from a first hand account—the Lewis and Clark expedition. While the expedition returned from the West by 1806, the official account of their journey wasn’t published until 1814 . In that interstitial period, though, some partial reports were published, and some unofficial copies were floating around. The 1983 paper that Woodman found traced much of the information in Le Raye’s account to the journal of Patrick Gass, a member of the Lewis and Clark expedition; Cutler, the likely author of the fake journal, also had access to an unpublished version of Meriwether Lewis’s Statistical view and perhaps the journals of other members of the expedition.

When Cutler released his book in 1812, he was publishing some biological data that had never been made public before. It’s just that he obfuscated where it had come from—most likely to boost sales of his book with a scintillating captivity tale. The mystery of the mule deer had a very tidy ending: the information that Rafinesque used to describe the species was not made up—it had just been aggregated into another work, with very bad sourcing.

A pair of mule deer (Photo: Geoffrey Kuchera/Shutterstock.com)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook