The Pair of American Politicians Who Fought the 19th Century’s Silliest Duel

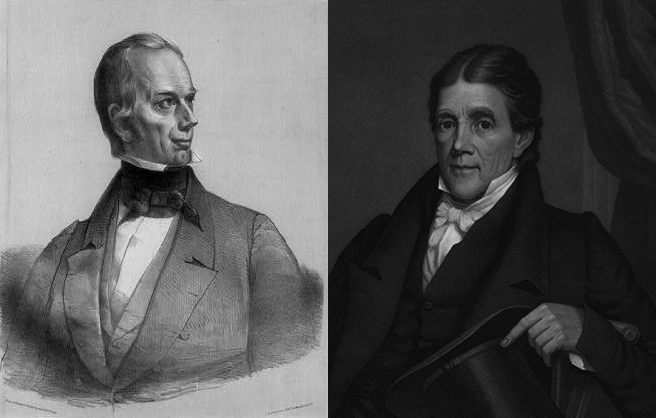

Henry Clay, left, and John Randolph of Roanoke, both deeply unimpressed. (Photos: Clay, Library of Congress; Randolph, Library of Congress)

In 2006 Vice President Cheney shot his friend Harry Whittington during a quail hunt. It was Big News.

In the 19th century, however, politicians shot at their nearest and dearest all the time, arranging duels over honor, personal pride, and, sometimes, the pettiest of grievances. Andrew Jackson, according to some accounts, participated in 103 duels before becoming president, including an 1806 episode in which he shot and killed Charles Dickinson because the man insulted his wife and accused Jackson of cheating on a horse race.

That’s a pretty petty reason for a fight to the death, but it is no match for the 19th century’s most peculiar, slapstick celebrity duel: an 1826 fight between John Randolph and Henry Clay. This was no Hamilton-Burr deathmatch. It was infinitely more ridiculous.

Congressman, Senator, Speaker of the House, Secretary of State, über-orator and five-time presidential also-ran, Clay is a renowned figure in American history. He was also a dueling enthusiast who once called out Congressman Humphrey Marshall for wearing British finery, rather than simple homespun garb, during an 1809 General Assembly. Had the technology existed, Clay would have been a solid casting choice for the reality show Real House-members of Washington, DC.

The steely gaze of Henry Clay, self-appointed arbiter of congressional fashion, c. 1850. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Randolph—generally called John Randolph of Roanoke (1773-1833)—is an almost implausibly fascinating character. From an old, wealthy, prominent Virginia family, Randolph was an eccentric, hard-drinking, tubercular, opium-eating tobacco-plantation owner who helped found the American Colonization Society, which repatriated slaves to Liberia. He was not only Thomas Jefferson’s cousin but also a descendant of Pocahontas.

A prodigy, Randolph was first elected to Congress at 26, in 1799. By age 30 he’d split with Jefferson and the Democratic-Republican party, which he felt had become crypto-Federalist, and formed the Tertium Quids, a group that fancied itself as representing the true Republican ideal of states’ rights and small government. Randolph was also something of a fop who went “to the House booted and spurred, with his whip in his hand,” according to Senator William Plumer of New Hampshire.

What more can you say about the man? Quite a lot, as it turns out. He was a lifelong bachelor and prepubescent as the result of childhood tuberculosis or Klinefelter’s syndrome—accounts vary. In any event, he couldn’t grow a beard and his voice was soprano-high. According to Edgar Allen Forbes in the New York Tribune (1915), Randolph was, early in his career, a presidential hopeful, yet bitter attacks on public figures held him back. His friends suggested that he was insane, in a peculiar attempt to excuse his behavior, while his enemies claimed he was a drunk. Randolph himself said that he merely had an incorrigible temper.

Randolph was a champion of swearing and public insult. He once referred to senator Daniel Webster as “a vile slanderer,” accused President Adams of being a “traitor,” and called statesman Edward Livingston “the most contemptible and degraded of beings, whom no man ought to touch, unless with a pair of tongs.” He especially loathed Congressman Willis Alston. An 1804 argument between the two at a DC boardinghouse led to a violent skirmish with knives and forks. Alston later called Randolph a “puppy,” leading to fisticuffs in a House stairway. Randolph caned Alston into a bloody mess, for which he was fined $20.

An autographed portrait of John Randolph. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

When not casting aspersions on colleagues, Randolph was, to put it in formal terms, “requesting satisfaction.” His first duel was precipitated by a mispronunciation. There were, apparently, some grammatical crimes up with which he simply would not put. While undergraduates at William & Mary, Randolph and Robert Taylor disagreed about which syllable to stress in the word “omnipotent.” Randolph—“a stickler for correct orthoepy,” according to his 1922 biographer William Cabell Bruce—wounded Taylor’s buttocks, but soon afterwards they became close friends.

As for Henry Clay, he and Randolph were frenemies who, more often than not, were teetering on the cusp of a brawl. In 1826, during an especially nasty bit of mudslinging in the Senate, which at the time resembled The Jerry Springer Show, Randolph called Secretary of State Clay the B-word—blackleg. This epithet refers to a card-cheat and should never be used in polite company, or even among politicians. Clay challenged Randolph to a duel.

According to contemporaneous etiquette, Clay should have demurred. Senators were permitted to disparage rivals, on the Floor, without recourse to pistols. Clay, for some reason, assumed that Randolph had revoked this privilege and Randolph, instead of correcting this misapprehension, agreed to the duel. Because he wasn’t terribly magnanimous, Randolph made a point of reminding everyone that Clay had no right to issue the challenge in the first place.

Randolph was, as ever, more interested in making a grand gesture than in actually fighting. He planned to shoot over Clay’s shoulder and assured Senator Thomas Hart Benton “in tones as sweet as woman’s own” that he would “‘do nothing on the morrow to disturb the sleep of the child or the repose of the mother.’” This is a prime example of Randolph’s expert trash-talking. In classic tough-guy mode, he spent the night before the duel reading poetry.

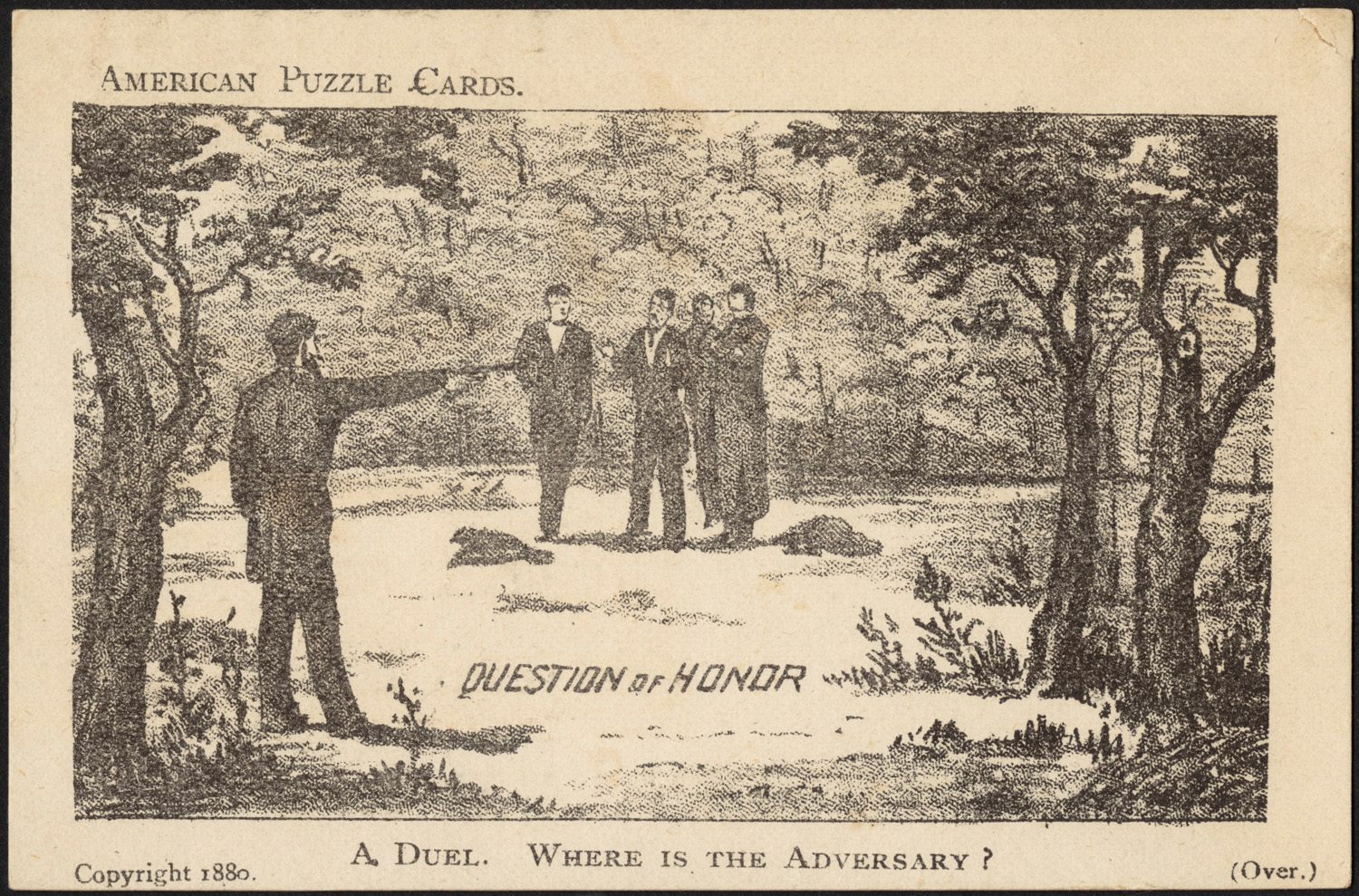

Not showing up for a duel: very bad form. (Photo: Boston Public Library/flickr)

On April 8 at sundown, Randolph and Clay met in North Arlington, Virginia, where Pimmit Run spills into the Potomac. Though dueling was illegal in the Old Dominion, Randolph wanted to die, if it came to that, on his home soil. Each party had two seconds and a surgeon. Benton was also there, perhaps with a bag of popcorn. Randolph showed up wearing a ridiculously oversized morning gown, which made it difficult for Clay to take aim—a cunning, if not quite gentlemanly, ploy.

The atmosphere was tense. Randolph appeared nervous and fidgety. He confided to Benton that he might fire at Clay after all, if there was malice in his opponent’s eye. While the pistols were being prepared, Randolph complained that his “thick buck-skin glove” would “destroy the delicacy” of his aim. Indeed, his pistol discharged prematurely because it was set to hair-trigger. Clay allowed him to reload for a mulligan.

The two men lined up, marched 30 paces—or 10; accounts vary—turned, and fired. Randolph, perhaps emasculated by his earlier misfire, tried to shoot Clay, but the shot was wide. Clay aimed and fired, wounding his opponent’s overcoat.

Our heroes braced themselves for round two. They both missed, again. Perhaps on purpose. Drunk frat-boys playing with daddy’s pistols. Clay called off the fight. Honor had been—somehow—restored.

Afterward, the two men shook hands. They were friends again. Randolph purportedly said, “Mr. Clay, you owe me a new coat.” History cannot confirm Clay’s response but some say he suggested writing a sit-com based on their misadventures.

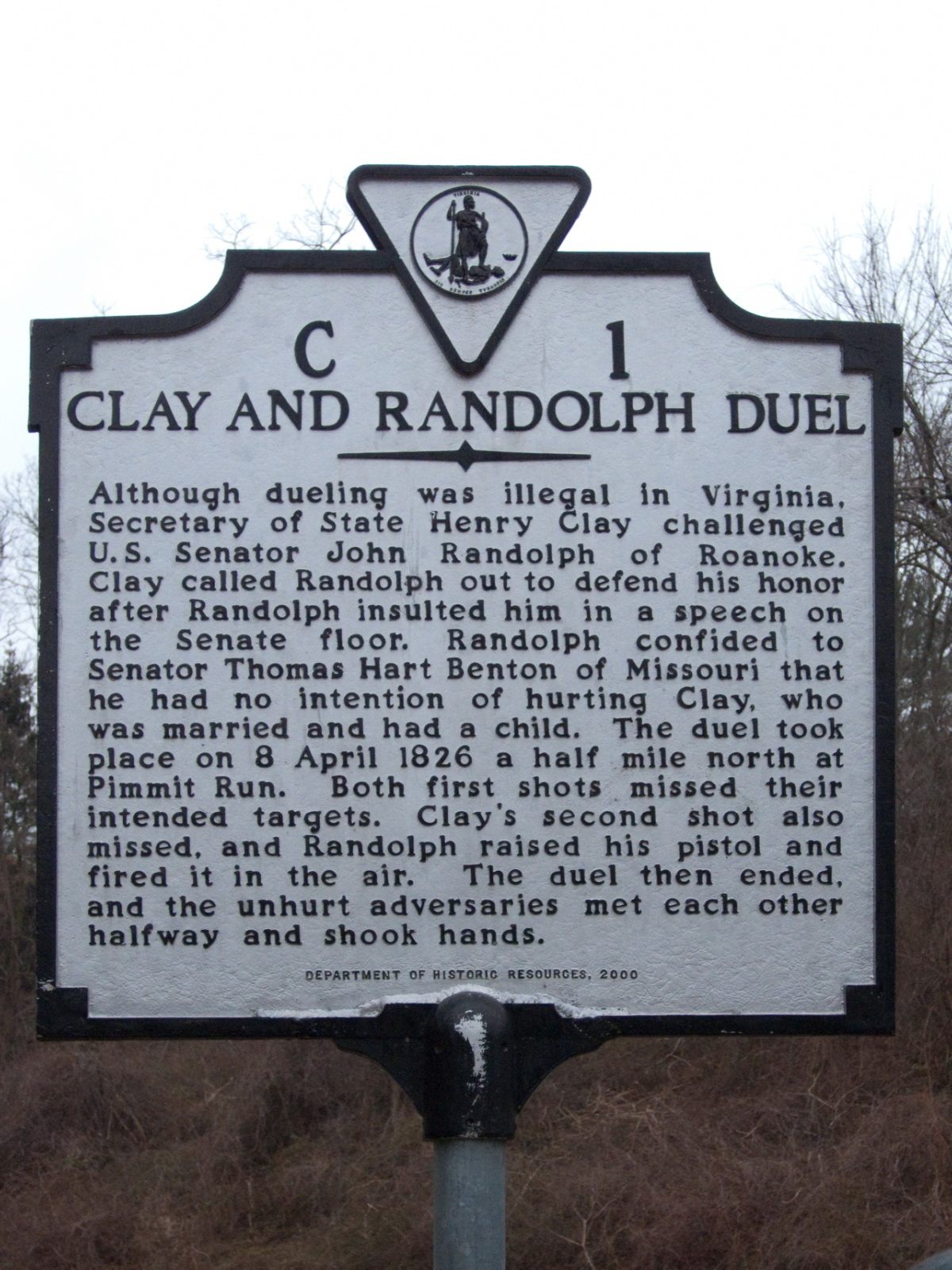

The marker at the site of the duel, where both men kept their dignity, and their lives. (Photo: Cliff/flickr)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook