The First Ever Stethoscope Was a Simple Wooden Tube

Happy 200th birthday, respiratory instrument!

Dr. Paul-Ferdinand Gachet’s 19th-century stethoscope. (Photo: Wellcome Images/CC SA: BY 4.0)

Dr. Paul-Ferdinand Gachet’s 19th-century stethoscope. (Photo: Wellcome Images/CC SA: BY 4.0)At the Necker Hospital in Paris, Dr. René Laennec stood at the bedside of a female patient who complained of heart trouble. To better understand this woman’s ailment, the doctor had limited options. This was 1816, and the standard procedure for auscultation—listening to the respiratory system—involved putting one’s ear against a patient’s chest to hear the heart and lungs.

This specific case was awkward for Dr. Laennec. He believed the normal method would be improper and ineffective for the woman, due to her being overweight. Instead of placing his ear on her chest, he rolled a piece of paper into a tube, and put it between his ear and the woman’s heart.

Laennec found that the telescope-shaped instrument amplified the sound of the beating heart and respiring lungs. He had avoided the embarrassment of putting his head near the lady’s breasts, and at the same time, invented the stethoscope.

Dr. Laennec and his new invention in action. (Photo: Public domain)

Dr. Laennec and his new invention in action. (Photo: Public domain)This cylinder is not what we now imagine a stethoscope to look like. But Laennec’s seemingly accidental discovery lay the origins for the device that is now slung around doctors’ necks.

The new method of mediate ausculation (indirect listening), a phrase coined by Dr. Laennec, soon took off and eventually became standard practice among doctors in France and elsewhere.

The photograph above of the smooth, wooden and cylindrical stethoscope is a typical example of an early version of Laennec’s invention. And this exact item was owned by a quite extraordinary physician.

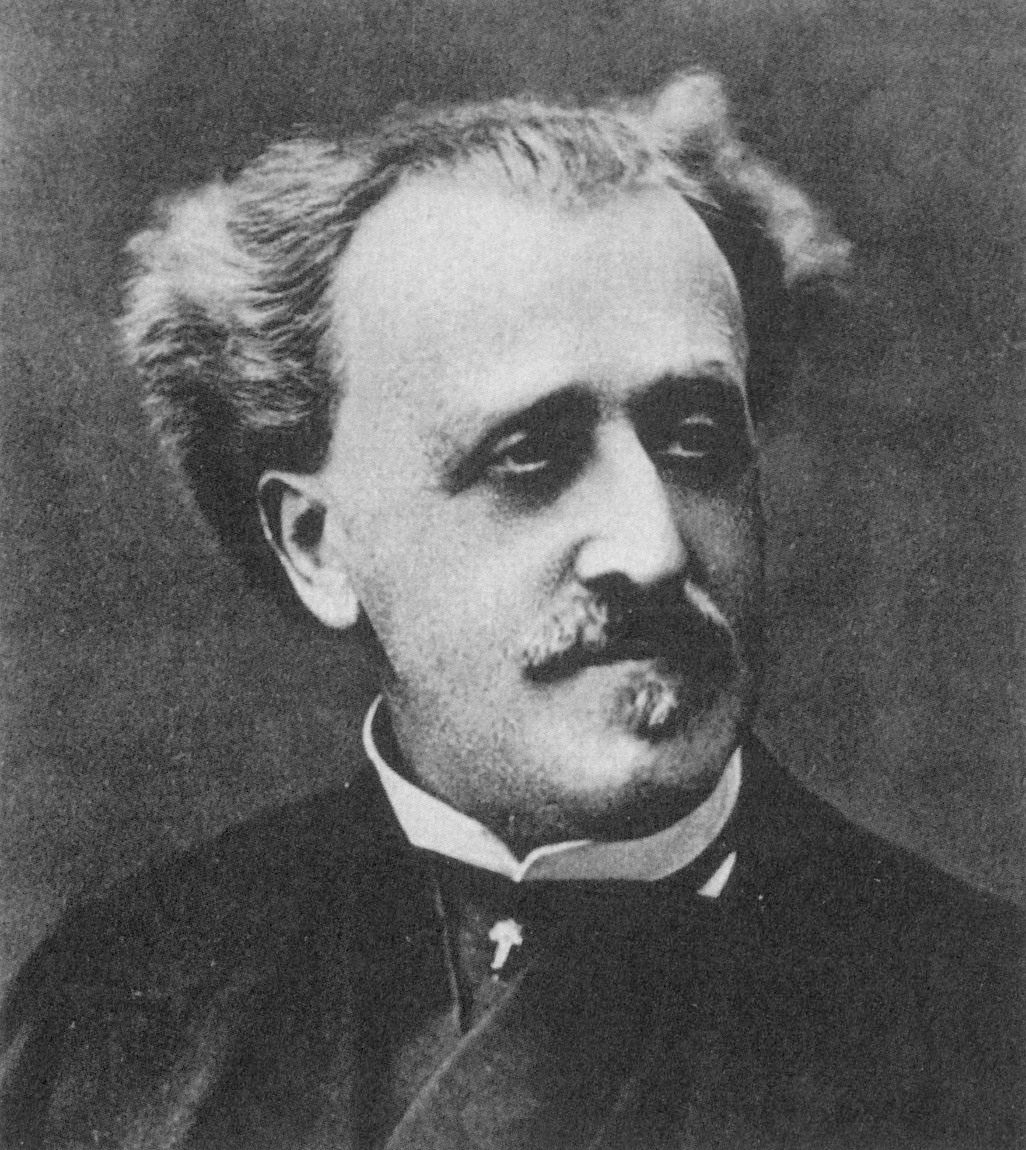

A passionate art collector and friend to many of the leading Impressionist painters, Dr. Gachet. (Photo: Public domain)

A passionate art collector and friend to many of the leading Impressionist painters, Dr. Gachet. (Photo: Public domain)The stethoscope was the property of Dr. Paul-Ferdinand Gachet, who must be one of the most hipster medical practitioners of all time. Gachet hung around Parisian cafes in the mid-1850s with Manet, Pissarro and Baudelaire, the poet. He would swap his own homeopathic remedies and medical consultations for his friends’ artwork, according to Artnet. He was a pal of many of the leading painters from around the era of the Impressionism movement including Cézanne, Monet, Manet and Renoir.

Gachet was best known in artistic circles for his unique healing powers. Not necessarily with the aid of his trusted stethoscope, but with his mind. He was a homeopathic doctor and interested in chiromancy—a form of palm reading.

A reputation for improving people’s psychological well-being led him to the Dutch master painter Vincent van Gogh. The doctor became “inseparably entwined with the last period of Vincent van Gogh’s life,” says the Musée d’Orsay’s website.

The pair met and then lived together in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise in 1890 after Van Gogh had departed a mental asylum. Gachet cared for the artist, and acted as his muse during van Gogh’s final few months. The Dutchman painted the doctor, in a portrait that Van Gogh described as a reflection of “the desolate expression of our time.”

Sadly, Gachet’s curative influence was not enough to save the tortured artist, who died by suicide soon after he finished the portrait.

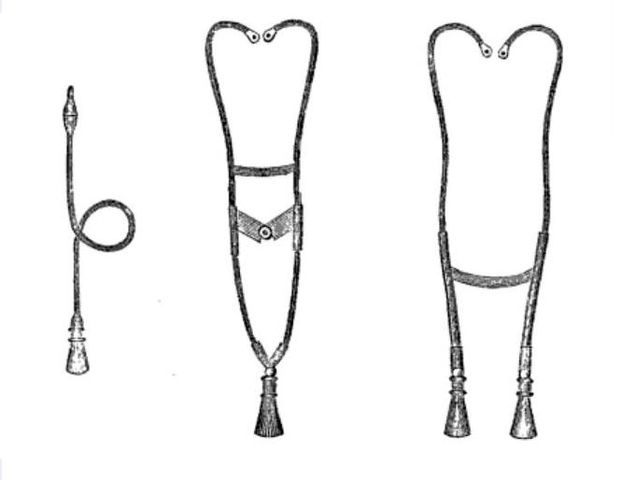

After Laennec’s groundbreaking discovery, inventors in the medical profession were quick to improve the first design. Dr. Golding Bird applied the new technology to a flexible, single-eared piece of equipment. By the 1850s, the single-tubed stethoscope was replaced by a binaural device.

The evolution of the stethoscope after Laennec’s first invention. (Photo: Samuel Wilks/Public domain)

The evolution of the stethoscope after Laennec’s first invention. (Photo: Samuel Wilks/Public domain)George Camman, a New York City physician, developed the first of these that became widely available. Made in 1852, the Camman’s Stethoscope was built from two ivory ear pieces, connected to tubes made from silver that were fixed at a hinge. Two smaller tubes, covered in silk, were attached to a conical-shaped piece that would be placed on the heart. This design is much closer to the instrument we recognize today.

If you’d like to see one of the kaleidoscope-esque originals, one of Laennec’s early monaural instruments is displayed at the Wood Library-Museum of Anesthesiology in Schaumburg, Illinois.

Object of Intrigue is a weekly column in which we investigate the story behind a curious item. Is there an object you want to see covered? Email ella@atlasobscura.com.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook