The Father of Modern French Cuisine Wrote a Very Misguided Thanksgiving Cookbook

Auguste Escoffier really didn’t get Thanksgiving.

In the world of fine dining, Auguste Escoffier has had a greater influence than perhaps any other chef in history. When his canonical cookbook, Le Guide Culinaire, was published in 1903, it set the standard for fancy food, moving systematically through stocks, sauces, aspic jellies, omelets, consommés, sweetbreads, rabbits, truffles, canapés, and every other fussy French preparation imaginable. More than a century later, his recipes still guide ambitious cooks: anyone who’s felt it necessary to learn to make the five “mother sauces” can blame Escoffier.

But while even today fancy chefs refer to Le Guide Culinaire as a foundational text, a cookbook Escoffier wrote in 1911 has fallen into complete obscurity. That year, the famous French chef took on the most American of food challenges—Thanksgiving. He got it almost entirely wrong.

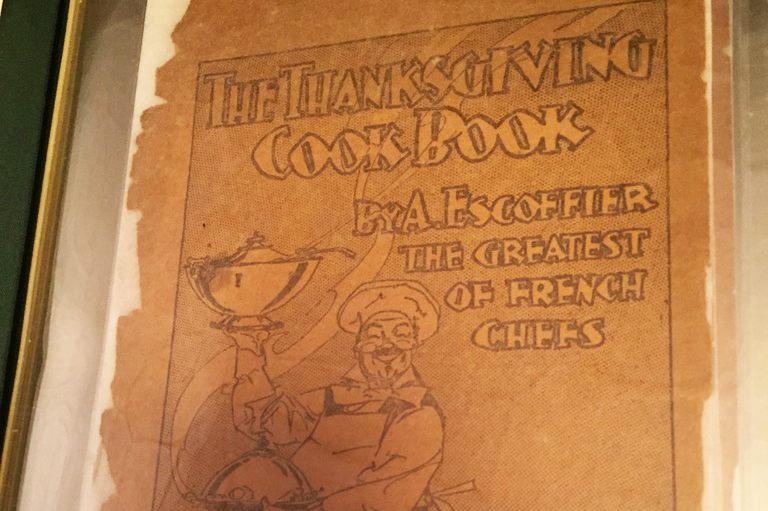

Escoffier’s Thanksgiving Cookbook was published as a supplement to the Sunday edition of a Hearst paper named, most patriotically, The American. The cookbook was 32 pages of commentary and recipes from Escoffier, “the Greatest of French Chefs,” who had supposedly selected dishes suited for American tastes.

The book was intended to double as a guide for home cooks preparing a Thanksgiving meal and an intro to French cooking. Escoffier did include a suggested menu for a multi-course Thanksgiving meal. Strangely, though, it did not have any of the dishes we’d now associate with Thanksgiving—no turkey, no mashed or sweet potatoes, no stuffing, no gravy, no green beans or brussels sprouts, no squash of any kind, no cranberry sauce, and no pumpkin pie.

Instead, in the cookbook, Escoffier offered 12 separate recipes for rabbit, a chapter on ragouts that featured only mutton, recipes for tomato sauce and macaroni; “some new ways for preparing tomatoes” including “Tomatoes à la Americaine” (basically tomatoes sliced and sprinkled with salt, pepper, vinegar and oil); crawfish recipes and tips on making cream soups.

His suggested Thanksgiving menu was based on a meal he’d had in Perigueux, a town in southwestern France known for its truffles. It included an omelette of potatoes and bacon, veal sweetbreads with spinach, a roast saddle of lamb, celery salad, sautéed mushrooms, and partridge terrine. There was only one dish mentioned in the whole cookbook that an American might recognize as Thanksgiving fare: a pie of “carameled apples,” for which no recipe was given.

Thanksgiving is an invented holiday, first officially established by Abraham Lincoln in 1863 and moved to its current position on the calendar by Franklin D. Roosevelt. By 1911, Thanksgiving menus usually contained the foods we think of as standard Thanksgiving dishes—turkey, cranberry sauce, and all the rest—but weren’t quite as codified as they are today.

One menu published in 1911, for instance, included roasted stuffed turkey, brown gravy, sweet potatoes, cranberry conserve, and pumpkin pie, but also featured oysters with sherry, chicken pie, and something called “puritan pudding.” That same year, a Boston Globe columnist engineered a “frugal” Thanksgiving menu featuring potato soup, dried herring, oatmeal mush, bread pudding, and corned beef hash. It wasn’t until World War II, when Norman Rockwell put a giant turkey at the center of his painting “Freedom from Want,” that the Thanksgiving menu in its current form was truly mythologized.

Even with some flexibility in the Thanksgiving menu, though, French food wasn’t an obvious fit for the most self-consciously American of all American holidays. Americans had inherited a suspicion of French cuisine from their British forebearers (who took some lessons from the French but did not adopt their willingness to make the most of offal or of animals like snails and frogs). Among elite Americans, from Thomas Jefferson onward, French cooking had cachet, but that taste never became popular.

“By the turn of the 20th century, French food would still have been really elite,” says Jennifer Jensen Wallach, associate professor at University of North Texas and the author of How America Eats. “There still wasn’t an extensive dining culture, but to the extent that it existed, it was French. The menus were French and designed to be exclusionary and elite. It’s not the kind of food Americans would have identified with.”

To his credit, Escoffier seemed to understand that Americans didn’t think of French cooking as food for average people. In his Thanksgiving cookbook, he took pains to explain that the recipes he had picked were economical and representative of French household cooking, not fancy restaurant food. He focused on rabbit because of its low price, “especially suited to families where economy is important.” He emphasized that ragout, in France, was a “respectable dish in domestic cookery,” and that pot-au-feu was a cost-effective meal. He lamented that Americans didn’t make better use of all their very good vegetables but chose to include the tomato because “its moderate price makes it accessible to all purses.”

Escoffier’s best efforts to speak to the American masses, though, did not land. “The emphasis on game and on organ meat would have been typical of French lower middle class food,” and the idea of making the most of all foods, says Andrew Haley, a historian at the University of Southern Mississippi. Around this same time, American reformers were advocating for a similar reform of cooking among poor Americans. But lower class Americans were not interested in carefully preparing cheaper cuts of meat to get the most value out from them.

“I don’t think Escoffier’s attempt to reach out would have been well received, because those efforts by Americans to do the same thing were not well received. They were seen as patronizing,” says Haley. “Americans wanted to buy better cuts of meat when they could afford them.”

In 1911, too, American food culture was slowly changing. Middle class Americans were starting to dine out more but, as Haley explains in his book, Turning the Tables, the way they asserted their identity was by rejecting French food in favor of American food. Escoffier had come to America in 1910 to oversee the expansion of the Ritz-Carlton restaurant in New York, but by then the Waldorf-Astoria was already serving its more Americanized version of fancy food, including the famous Waldorf salad.

Escoffier’s attitude towards Americans and their food didn’t do him any favors. He praises American ingredients but doesn’t seem to think much of American diners or cooks. “Americans have an abundance of good, cheap vegetables at their command, and they do not make a sufficient use of them or prepare them in as many attractive ways as would be possible,” he writes. He doesn’t understand why Americans aren’t more interested in crawfish, either. “Probably if the virtues of bisque of crawfish were thoroughly understood, it would become as popular in America as in France,” he writes.

His instincts in this case are misplaced, though. He’s so proud of the Thanksgiving menu he put together and so confident of it! He writes, of the meal he had in Perigueux, “The midday repast to which I was entertained was remarkable as an example of the best French household cooking, and I feel sure that it will interest my American readers as a possible menu for Thanksgiving Day.”

He was probably right about that first part—anyone looking for a French menu for a fancy feast might consider this one. But, as much as his influence was felt in the rest of food world, Escoffier’s attempt at creating an American meal had zero influence on Thanksgiving.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook